(Press-News.org) Could cactus pear become a major crop like soybeans and corn in the near future, and help provide a biofuel source, as well as a sustainable food and forage crop? According to a recently published study, researchers from the University of Nevada, Reno believe the plant, with its high heat tolerance and low water use, may be able to provide fuel and food in places that previously haven't been able to grow much in the way of sustainable crops.

Global climate change models predict that long-term drought events will increase in duration and intensity, resulting in both higher temperatures and lower levels of available water. Many crops, such as rice, corn and soybeans, have an upper temperature limit, and other traditional crops, such as alfalfa, require more water than what might be available in the future.

"Dry areas are going to get dryer because of climate change," Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Professor John Cushman, with the University's College of Agriculture, Biotechnology & Natural Resources, said. "Ultimately, we're going to see more and more of these drought issues affecting crops such as corn and soybeans in the future."

Fueling renewable energy

As part of the College's Experiment Station unit, Cushman and his team recently published the results of a five-year study on the use of spineless cactus pear as a high-temperature, low-water commercial crop. The study, funded by the Experiment Station and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture, was the first long-term field trial of Opuntia species in the U.S. as a scalable bioenergy feedstock to replace fossil fuel.

Results of the study, which took place at the Experiment Station's Southern Nevada Field Lab in Logandale, Nevada, showed that Opuntia ficus-indica had the highest fruit production while using up to 80% less water than some traditional crops. Co-authors included Carol Bishop, with the College's Extension unit, postdoctoral research scholar Dhurba Neupane, and graduate students Nicholas Alexander Niechayev and Jesse Mayer.

"Maize and sugar cane are the major bioenergy crops right now, but use three to six times more water than cactus pear," Cushman said. "This study showed that cactus pear productivity is on par with these important bioenergy crops, but use a fraction of the water and have a higher heat tolerance, which makes them a much more climate-resilient crop."

Cactus pear works well as a bioenergy crop because it is a versatile perennial crop. When it's not being harvested for biofuel, then it works as a land-based carbon sink, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in a sustainable manner.

"Approximately 42% of land area around the world is classified as semi-arid or arid," Cushman said. "There is enormous potential for planting cactus trees for carbon sequestration. We can start growing cactus pear crops in abandoned areas that are marginal and may not be suitable for other crops, thereby expanding the area being used for bioenergy production."

Fueling people and animals

The crop can also be used for human consumption and livestock feed. Cactus pear is already used in many semi-arid areas around the world for food and forage due to its low-water needs compared with more traditional crops. The fruit can be used for jams and jellies due to its high sugar content, and the pads are eaten both fresh and as a canned vegetable. Because the plant's pads are made of 90% water, the crop works great for livestock feed as well.

"That's the benefit of this perennial crop," Cushman explained. "You've harvested the fruit and the pads for food, then you have this large amount of biomass sitting on the land that is sequestering carbon and can be used for biofuel production."

Cushman also hopes to use cactus pear genes to improve the water-use efficiency of other crops. One of the ways cactus pear retains water is by closing its pores during the heat of day to prevent evaporation and opening them at night to breathe. Cushman wants to take the cactus pear genes that allow it to do this, and add them to the genetic makeup of other plants to increase their drought tolerance.

Bishop, Extension educator for Northeast Clark County, and her team, which includes Moapa Valley High School students, continue to help maintain and harvest the more than 250 cactus pear plants still grown at the field lab in Logandale. In addition, during the study, the students gained valuable experience helping to spread awareness about the project, its goals, and the plant's potential benefits and uses. They produced videos, papers, brochures and recipes; gave tours of the field lab; and held classes, including harvesting and cooking classes.

Fueling further research

In 2019, Cushman began a new research project with cactus pear at the U.S. Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service' National Arid Land Plant Genetic Resources Unit in Parlier, California. In addition to continuing to take measurements of how much the cactus crop will produce, Cushman's team, in collaboration with Claire Heinitz, curator at the unit, is looking at which accessions, or unique samples of plant tissue or seeds with different genetic traits, provide the greatest production and optimize the crop's growing conditions.

"We want a spineless cactus pear that will grow fast and produce a lot of biomass," Cushman said.

One of the other goals of the project is to learn more about Opuntia stunting disease, which causes cactuses to grow smaller pads and fruit. The team is taking samples from the infected plants to look at the DNA and RNA to find what causes the disease and how it is transferred to other cactuses in the field. The hope is to use the information to create a diagnostic tool and treatment to detect and prevent the disease's spread and to salvage usable parts from diseased plants.

INFORMATION:

In addition, the team is investigating different pesticides that can be used on the plants that won't harm humans, or the bees that pollinate the plants.

For more information on the five-year study's results, see: " END

In early 2016, an icy visitor from the edge of our solar system hurtled past Earth. It briefly became visible to stargazers as Comet Catalina before it slingshotted past the Sun to disappear forevermore out of the solar system.

Among the many observatories that captured a view of this comet, which appeared near the Big Dipper, was the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), NASA's telescope on an airplane. Using one of its unique infrared instruments, SOFIA was able to pick out a familiar fingerprint within the dusty glow of the comet's tail--carbon.

Now this one-time visitor to our inner solar system is helping explain ...

When stay-at-home orders were announced as one of the greatest tools in our arsenal against the COVID-19 pandemic, anyone who's vintage enough to have watched forward-looking shows and movies-- from "The Jetsons" to "Star Trek" to "Back to the Future" -- might have thought America was ready to embrace a world where video calling and other tech-heavy communication options reigned supreme.

But one year, dozens of Zoom meetings, hundreds of phone calls and text messages, thousands of online gaming hours, and millions of social media posts later, new research led by UNLV has ...

Researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) found large quantities of previously undetectable compounds from the family of chemicals known as PFAS in six watersheds on Cape Cod using a new method to quantify and identify PFAS compounds. Exposures to some PFAS, widely used for their ability to repel heat, water, and oil, are linked to a range of health risks including cancer, immune suppression, diabetes, and low infant birth weight.

The new testing method revealed large quantities of previously undetected PFAS from fire-retardant foams and other unknown sources. Total concentrations of PFAS present in these watersheds were above state maximum contaminant ...

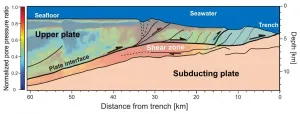

Researchers from Japan and Indonesia have pioneered a new method for more accurately estimating the source of weak ground vibrations in areas where one tectonic plate is sliding under another in the sea. Applying the approach to Japan's Nankai Trough, the researchers were able to estimate previously unknown properties in the region, demonstrating the method's promise to help probe properties needed for better monitoring and understanding larger earthquakes along this and other plate interfaces.

Episodes of small, often imperceptible seismic events ...

African American breast cancer survivors are four times more likely to die from breast cancer than women of all other races and ethnicities, and they have a disproportionately high rate of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD).

New research led by George Mason University's College of Health and Human Services faculty Dr. Michelle Williams assessed African American breast cancer survivors' risk factors and knowledge about CVD in the Deep South, where health disparities between African American women and women of other races is even larger. They found that although African American breast cancer survivors have a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors, their knowledge about CVD is low.

The study was published in the Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice in February. ...

UPTON, NY—Physicists studying collisions of gold ions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, are embarking on a journey through the phases of nuclear matter—the stuff that makes up the nuclei of all the visible matter in our universe. A new analysis of collisions conducted at different energies shows tantalizing signs of a critical point—a change in the way that quarks and gluons, the building blocks of protons and neutrons, transform from one phase to another. The findings, just published by RHIC’s STAR Collaboration in the journal Physical ...

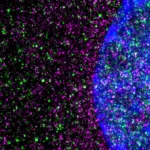

Patients can spend up to six years waiting for a kidney transplant. Even when they do receive a transplant, up to 20 percent of patients will experience rejection. Transplant rejection occurs when a recipient's immune cells recognize the newly received kidney as a foreign organ and refuse to accept the donor's antigens. Current methods for testing for kidney rejection include invasive biopsy procedures, causing patients to stay in the hospital for multiple days. A study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital and Exosome Diagnostics proposes a new, noninvasive ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Studies of the microbiome in the human gut focus mainly on bacteria. Other microbes that are also present in the gut -- viruses, protists, archaea and fungi -- have been largely overlooked.

New research in mice now points to a significant role for fungi in the intestine -- the communities of molds and yeasts known as the mycobiome -- that are the active interface between the host and their diet.

"We showed that the gut mycobiome of healthy mice was shaped by the environment, including diet, and that it significantly correlated with metabolic outcomes," said Kent Willis, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-corresponding author of the study, published in the journal Communications Biology. "Our results ...

JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold ...

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...