(Press-News.org) The "three-body problem," the term coined for predicting the motion of three gravitating bodies in space, is essential for understanding a variety of astrophysical processes as well as a large class of mechanical problems, and has occupied some of the world's best physicists, astronomers and mathematicians for over three centuries. Their attempts have led to the discovery of several important fields of science; yet its solution remained a mystery.

At the end of the 17th century, Sir Isaac Newton succeeded in explaining the motion of the planets around the sun through a law of universal gravitation. He also sought to explain the motion of the moon. Since both the earth and the sun determine the motion of the moon, Newton became interested in the problem of predicting the motion of three bodies moving in space under the influence of their mutual gravitational attraction (see attached illustration), a problem that later became known as "the three-body problem".

However, unlike the two-body problem, Newton was unable to obtain a general mathematical solution for it. Indeed, the three-body problem proved easy to define, yet difficult to solve.

New research, led by Professor Barak Kol at Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Racah Institute of Physics, adds a step to this scientific journey that began with Newton, touching on the limits of scientific prediction and the role of chaos in it.

The theoretical study presents a novel and exact reduction of the problem, enabled by a re-examination of the basic concepts that underlie previous theories. It allows for a precise prediction of the probability for each of the three bodies to escape the system.

Following Newton and two centuries of fruitful research in the field including by Euler, Lagrange and Jacobi, by the late 19th century the mathematician Poincare discovered that the problem exhibits extreme sensitivity to the bodies' initial positions and velocities. This sensitivity, which later became known as chaos, has far-reaching implications - it indicates that there is no deterministic solution in closed-form to the three-body problem.

In the 20th century, the development of computers made it possible to re-examine the problem with the help of computerized simulations of the bodies' motion. The simulations showed that under some general assumptions, a three-body system experiences periods of chaotic, or random, motion alternating with periods of regular motion, until finally the system disintegrates into a pair of bodies orbiting their common center of mass and a third one moving away, or escaping, from them.

The chaotic nature implies that not only is a closed-form solution impossible, but also computer simulations cannot provide specific and reliable long-term predictions. However, the availability of large sets of simulations led in 1976 to the idea of seeking a statistical prediction of the system, and in particular, predicting the escape probability of each of the three bodies. In this sense, the original goal, to find a deterministic solution, was found to be wrong, and it was recognized that the right goal is to find a statistical solution.

Determining the statistical solution has proven to be no easy task due to three features of this problem: the system presents chaotic motion that alternates with regular motion; it is unbounded and susceptible to disintegration. A year ago, Racah's Dr. Nicholas Stone and his colleagues used a new method of calculation and, for the first time, achieved a closed mathematical expression for the statistical solution. However, this method, like all its predecessor statistical approaches, rests on certain assumptions. Inspired by these results, Kol initiated a re-examination of these assumptions.

The infinite unbounded range of the gravitational force suggests the appearance of infinite probabilities through the so-called infinite phase-space volume. To avoid this pathology, and for other reasons, all previous attempts postulated a somewhat arbitrary "strong interaction region", and accounted only for configurations within it in the calculation of probabilities.

The new study, recently published in the scientific journal Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy, focuses on the outgoing flux of phase-volume, rather than the phase-volume itself. Since the flux is finite even when the volume is infinite, this flux-based approach avoids the artificial problem of infinite probabilities, without ever introducing the artificial strong interaction region.

The flux-based theory predicts the escape probabilities of each body, under a certain assumption. The predictions are different from all previous frameworks, and Prof. Kol emphasizes that "tests by millions of computer simulations shows strong agreement between theory and simulation." The simulations were carried out in collaboration with Viraj Manwadkar from the University of Chicago, Alessandro Trani from the Okinawa Institute in Japan, and Nathan Leigh from University of Concepcion in Chile. This agreement proves that understanding the system requires a paradigm shift and that the new conceptual basis describes the system well. It turns out, then, that even for the foundations of such an old problem, innovation is possible.

The implications of this study are wide-ranging and is expected to influence both the solution of a variety of astrophysical problems and the understanding of an entire class of problems in mechanics. In astrophysics, it may have application to the mechanism that creates pairs of compact bodies that are the source of gravitational waves, as well as to deepen the understanding of the dynamics within star clusters. In mechanics, the three-body problem is a prototype for a variety of chaotic problems, so progress in it is likely to reflect on additional problems in this important class.

INFORMATION:

PLYMOUTH MEETING, PA [April 13, 2021] -- The April 2021 issue of JNCCN--Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network publishes new research from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and Gustave Roussy Institute, which suggests that baseline brain imaging should be considered in most patients with metastatic kidney cancer. The researchers studied 1,689 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) who had been considered for clinical trial participation at either of the two institutions between 2001 and 2019 and had undergone brain imaging in this context, without clinical suspicion for brain involvement. The researchers discovered 4% had asymptomatic brain metastases in this setting. This group was found to have a low median 1-year ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - We've all seen them: political ads on television that promise doom gloom if Candidate X is elected, and how all your problems will be solved if you choose Candidate Y. And Candidate Y, of course, approves this message.

Beyond attempting to move a large swath of the population to vote one way or another, the seemingly constant bombardment of negativity in the name of our democratic process is anxiety-inducing, researchers have found.

"Many of my friends and family members wind up quite stressed out, for lack of a better word, during each election season," said Jeff Niederdeppe, professor in the Department of Communication in the College of ...

With 'Eyecam' they now present the prototype of a webcam that not only looks like a human eye, but imitates its movements realistically. "The goal of our project is not to develop a 'better' design for cameras, but to spark a discussion. We want to draw attention to the fact that we are surrounded by sensing devices every day. That raises the question of how that affects us," says Marc Teyssier. In 2020, the French scientist completed his doctorate on the topic of anthropomorphic design in Paris. Now he is a postdoctoral researcher in the Human-Computer Interaction Lab at Saarland University in Germany.

The research team at Saarland Informatics Campus has developed ...

Human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a little-understood condition that significantly increases the risk of inflammation, fibrosis and liver cancer and ultimately requires liver transplant.

"NAFLD has been difficult to study mainly because we had no good animal model," said corresponding author Dr. Karl-Dimiter Bissig, who was at Baylor during the development of this project and is now at Duke University.

The disease has both genetic and nutritional components, which have been hard to understand in human studies, and murine models ...

A new study verifies the age and origin of one of the oldest specimens of Homo erectus--a very successful early human who roamed the world for nearly 2 million years. In doing so, the researchers also found two new specimens at the site--likely the earliest pieces of the Homo erectus skeleton yet discovered. Details are published today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Homo erectus is the first hominin that we know about that has a body plan more like our own and seemed to be on its way to being more human-like," said Ashley Hammond, an assistant curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Division of Anthropology and the lead author of the new study. "It had longer lower limbs than upper limbs, a torso ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - The muon is a tiny particle, but it has the giant potential to upend our understanding of the subatomic world and reveal an undiscovered type of fundamental physics.

That possibility is looking more and more likely, according to the initial results of an international collaboration - hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory - that involved key contributions by a Cornell team led by Lawrence Gibbons, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The collaboration, which brought together 200 scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries, set out to confirm the findings of a 1998 experiment that startled physicists by indicating that muons' magnetic ...

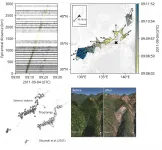

In the Cascadia subduction zone, medium and large-sized "intraslab" earthquakes, which take place at greater than crustal depths within the subducting plate, will likely produce only a few detectable aftershocks, according to a new study.

The findings could have implications for forecasting aftershock seismic hazard in the Pacific Northwest, say Joan Gomberg of the U.S. Geological Survey and Paul Bodin of the University of Washington in Seattle, in their paper published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers now calculate aftershock forecasts in the region based in part on data from subduction zones around the world. ...

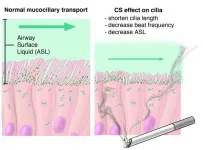

In a series of experiments that began with amoebas -- single-celled organisms that extend podlike appendages to move around -- Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have identified a genetic pathway that could be activated to help sweep out mucus from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a widespread lung ailment.

"Physician-scientists and fundamental biologists worked together to understand a problem at the root of a major human illness, and the problem, as often happens, relates to the core biology of cells," says Doug Robinson, Ph.D., professor of cell ...

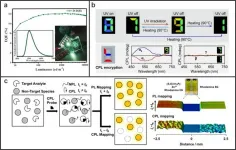

Circularly polarized light exhibits promising applications in future displays and photonic technologies. Traditionally, circularly polarized light is converted from unpolarized light by the linear polarizer and the quarter-wave plate. During this indirectly physical process, at least 50% of energy will be lost. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) from chiral luminophores provides an ideal approach to directly generate circularly polarized light, in which the energy loss induced by polarized filter can be reduced. Among various chiral luminophores, organic micro-/nano-structures have attracted increasing attention owing to the high quantum efficiency ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Tropical cyclones like typhoons may invoke imagery of violent winds and storm surges flooding coastal areas, but with the heavy rainfall these storms may bring, another major hazard they can cause is landslides--sometimes a whole series of landslides across an affected area over a short time. Detecting these landslides is often difficult during the hazardous weather conditions that trigger them. New methods to rapidly detect and respond to these events can help mitigate their harm, as well as better understand the physical processes themselves.

In a new study published in Geophysical Journal International, a research team led ...