(Press-News.org) Each year over 150,000 infants worldwide are infected with HIV in the womb, at birth, or through breastfeeding. Why transmission occurs in some cases but not others has long been a mystery, but now a team led by Weill Cornell Medicine and Duke University scientists has uncovered an important clue, with implications for how to eliminate infant HIV infections.

In a study published April 2 in PLoS Pathogens, the researchers found evidence linking mother-to-child transmission of HIV to rare variants of the virus in the mother's blood that are able to escape broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs)--an emerging type of treatment that can be used to block a wide range of HIV strains. The scientists also found that these HIV variants tend to contain key genetic signatures.

The findings provide a possible way to predict whether mother-to-infant transmission of HIV will occur and point the way towards approaches that can help prevent such transmission, the researchers said. At the same time, the results hint that treating HIV-positive pregnant women or new mothers with bnAb therapies might have the unintended effect of promoting the evolution of variants that can resist these therapies and thus raising the risk of mother-to-child transmission.

"Our findings suggest that vaccines or treatments for HIV-infected pregnant and nursing women should be designed to prevent the development of these resistant variants, in order to reduce the chance of HIV transmission to the child," said senior author Dr. Sallie Permar, chair of pediatrics and Nancy C. Paduano Professor in Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Mother-to-newborn transmission of HIV has been puzzling because, even when the mother is infected and untreated, the chance of transmission to the child is less than 50 percent. Scientists have hypothesized that the factors determining whether transmission occurs lie in the mother's immune system and/or in the HIV variants circulating in her blood. But zeroing in on the source of transmission risk has been challenging, not least because antiretroviral (ART) drug treatment, which is now standard for most HIV-infected individuals, would be likely to confound the results of any study of current patients.

Dr. Permar and her colleagues circumvented this problem by evaluating a collection of samples from a study of HIV-infected mothers and their infants conducted three decades ago, before the age of ART.

In one set of experiments, Dr. Permar's team isolated the HIV variants that had been transmitted from the mothers to their infants, and found that these transmitted HIV variants--compared to non-transmitted variants from the mothers' blood--were about 30 percent less sensitive to the mothers' plasma--the antibody-containing fraction of the mothers' blood. In other words, the difference between transmission and non-transmission seemed to be due at least in part to HIV variations that allow escape from maternal antibodies.

Detecting those HIV escape variants in the mothers was not a simple matter. The researchers observed that HIV variants in transmitting mothers and HIV variants in non-transmitting mothers were, on the whole, just as sensitive to maternal plasma.

Ultimately the researchers analyzed genetic sequences in the HIV variants from transmitting and non-transmitting mothers and found that several genetic signatures were associated with transmission vs. non-transmission.

Most of these signatures were also associated with the rare ability to escape neutralization by some or all of a panel of bnAbs. The latter are antibodies that were originally isolated from a few HIV-positive individuals, are known to block a wide variety of HIV strains and are being developed as HIV therapies.

"This finding suggests that the presence of broadly neutralizing antibody-escape variants in the blood of HIV-infected mothers is a predictor of higher transmission risk to newborns," Dr. Permar said.

That in turn indicates that any vaccine or treatment given to HIV-infected pregnant or nursing mothers, as an adjunct to ART to reduce transmission risk, needs to be effective against HIV variants that can escape these special antibodies.

Moreover, the results suggest that simply vaccinating mothers to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies, or delivering mixes of therapeutic bnAbs, might in some cases cause more mother-to-child transmission--if the presence of the potent antibodies promotes HIV evolution towards resistant variants.

Dr. Permar and colleagues are now working to understand better how to address this problem. Approaches worth investigating, Dr. Permar said, include giving pregnant, HIV-infected women high-dose, short-term combination bnAb therapy containing multiple types of these antibodies, in order to minimize escape risk; and also delivering a multi-bnAb therapy directly to babies at birth in the hope of curing any HIV infection that occurs during delivery and preventing subsequent HIV infection via breastfeeding.

INFORMATION:

3D printing has opened up a completely new range of possibilities. One example is the production of novel turbine buckets. However, the 3D printing process often induces internal stress in the components which can in the worst case lead to cracks. Now a research team has succeeded in using neutrons from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) research neutron source for non-destructive detection of this internal stress - a key achievement for the improvement of the production processes.

Gas turbine buckets have to withstand extreme conditions: under high pressure and at high temperatures they are exposed to tremendous centrifugal forces . In order to further maximize ...

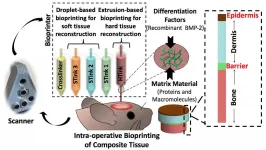

Fixing traumatic injuries to the skin and bones of the face and skull is difficult because of the many layers of different types of tissues involved, but now, researchers have repaired such defects in a rat model using bioprinting during surgery, and their work may lead to faster and better methods of healing skin and bones.

"This work is clinically significant," said Ibrahim T. Ozbolat, Hartz Family Career Development Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics, Biomedical Engineering and Neurosurgery, Penn State. "Dealing with composite defects, fixing hard and soft tissues at once, is difficult. And for the craniofacial area, the results have to be esthetically pleasing."

Currently, fixing a hole in the skull involving both bone and soft tissue requires using bone ...

The hormone prolactin has long been understood to play a vital role in breast growth and development and the production of milk during pregnancy. But a pair of recent studies conducted at VCU Massey Cancer Center finds strong evidence that prolactin also acts as a major contributor to breast cancer development and that the hormone could inform the creation of targeted drugs to treat multiple forms of the disease.

Hormones have proteins on their cell surface called receptors that receive and send biological messages and regulate cell function. Through research published in npj Breast Cancer, VCU Massey Cancer Center ...

One in five pharmacies refuse to dispense a key medication to treat addiction, according to new research.

The study, published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, was conducted by researchers at Oregon Health & Science University and the Oregon State University College of Pharmacy. Researchers called hundreds of pharmacies around the country to ask whether they would dispense Suboxone, also known as buprenorphine.

"Buprenorphine is a vital, lifesaving medication for people with opioid use disorder, but improving access has been a problem for a variety of reasons," said senior author Daniel Hartung, Pharm.D., M.P.H., professor in the College of Pharmacy. "Although anecdotes and smaller studies have suggested problems, our study is the first to systematically characterize this ...

A partnership between UC Davis and Maurice J. Gallagher, Jr., chairman and CEO of Allegiant Travel Company, has led to a new rapid COVID-19 test.

A recent study published Nature Scientific Reports shows the novel method to be 98.3% accurate for positive COVID-19 tests and 96% for negative tests.

"This test was made from the ground up," said Nam Tran, lead author for the study and a professor of pathology in the UC Davis School of Medicine. "Nothing like this test ever existed. We were starting with a clean slate."

The novel COVID-19 test uses an analytical instrument known as a mass spectrometer, which is paired with a powerful machine-learning platform to detect SARS-CoV-2 in nasal swabs. The mass spectrometer can analyze samples in minutes, with the ...

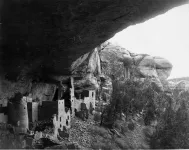

PULLMAN, Wash. - Climate problems alone were not enough to end periods of ancient Pueblo development in the southwestern United States.

Drought is often blamed for the periodic disruptions of these Pueblo societies, but in a study with potential implications for the modern world, archaeologists have found evidence that slowly accumulating social tension likely played a substantial role in three dramatic upheavals in Pueblo development.

The findings, detailed in an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that Pueblo farmers often persevered through droughts, but when social tensions were increasing, even modest droughts could spell the end of an era of ...

The risk of childhood undernutrition varies widely among villages in India, according to new research led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with researchers at Harvard's Center for Geographic Analysis, Harvard's Center for Population and Development Studies, Korea University, Microsoft, and the Government of India.

The study is the first to predict and map the burden of childhood undernutrition across all of the nearly 600,000 villages in rural India, and the methods developed to do so could be applied to other health indicators and help advance the field of "precision public health," in which interventions and policies are tailored to smaller populations that are disproportionally ...

One of the great mysteries of modern space science is neatly summed up by the view from NASA's Perseverance, which just landed on Mars: Today it's a desert planet, and yet the rover is sitting right next to an ancient river delta.

The apparent contradiction has puzzled scientists for decades, especially because at the same time that Mars had flowing rivers, it was getting less than a third as much sunshine as we enjoy today on Earth.

But a new study led by University of Chicago planetary scientist Edwin Kite, an assistant professor of geophysical sciences and an expert on climates of other worlds, uses a computer model to put forth a promising explanation: Mars ...

Understanding spoken words, developing normal speech - cochlear implants enable people with profound hearing impairment to gain a great deal in terms of quality of life. However, background noises are problematic, they significantly compromise the comprehension of speech of people with cochlear implants. The team led by Tobias Moser from the Institute for Auditory Neuroscience and InnerEarLab at the University Medical Center Göttingen and from the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory at the German Primate Center - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research (DPZ) is therefore working to improve cochlear implants. The scientists want to use genetic engineering methods to make the nerve cells in the ear ...

MADISON, Wis. -- In October of 2020, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their discovery of an adaptable, easy way to edit genomes, known as CRISPR, which has transformed the world of genetic engineering.

CRISPR has been used to fight lung cancer and correct the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia in stem cells. But the technology was also used by a Chinese scientist to secretly and illegally edit the genomes of twin girls -- the first-ever heritable mutation of the human germline made with genetic engineering.

"We've moved away from an era of science where we understood the risks that came with new technology and where decision stakes were ...