(Press-News.org) Several indicators point to the adverse impacts of climate change on the planet’s vegetation, but a little-known positive fact is the existence of climate-change refugia in which trees are far less affected by the gradual rise in temperatures and changing rainfall regimes. Climate-change refugia are areas that are relatively buffered from climate change, such as wetlands, land bordering water courses, rocky outcrops, and valleys with cold-air pools or inversions, for example.

A study conducted in Peruaçu Caves National Park in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, with FAPESP’s support, confirmed and quantified this type of occurrence. “These refugia are excellent candidates for land management initiatives, offering a high probability of success and lower expenditure in conservation areas,” said Milena Godoy-Veiga, a PhD candidate at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Biosciences (IB-USP) and lead author of the article on the study published in Forest Ecology and Management.

The other authors include Godoy-Veiga’s thesis advisers, Gregório Ceccantini and Giuliano Locosselli.

According to Godoy-Veiga, climate-change refugia are frequently located in karstic regions. Karst is a topography formed over time from chemical dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, etc., and characterized by underground drainage systems with subterranean rivers, sinkholes, and caves, as well as dramatic above-ground features such as steep cliffs and dry gullies. “This is the landscape in Peruaçu Caves National Park, where there are ground height differences of as much as 200 meters, with the high parts projecting shadows over the low parts, and the environment comprising all the other features mentioned,” she said.

The researchers reached the conclusion that climate-change refugia are to be found in a large proportion of the park by analyzing growth rings in samples of the tree species Amburana cearensis (vernacular names amburana-de-cheiro and cerejeira). “We counted over 4,500 growth rings in samples from 39 trees,” Godoy-Veiga said. “Chronological analysis is usually done with a mean value for all trees, but we were able to analyze each tree individually thanks to a partnership with two researchers at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, who are also co-authors of the article: Elisabetta Boaretto, who heads a laboratory, and Lior Regev, the scientist responsible for the particle accelerator in which radiocarbon dating is done.”

They were able to date the tree rings precisely using the “bomb peak” curve, which is applicable to modern samples owing to the sharp rise in carbon-14 levels in the atmosphere and all living beings following the nuclear tests conducted during the Cold War. The levels peaked in the mid-1960s and then fell again with the signing of various international treaties banning nuclear weapons tests.

“Our analysis shows that 22 out of 39 trees were sensitive to temperature and the amount of summer rain. Six were sensitive only to rainfall, and 11 were apparently not affected by the region’s weather. Based on these results, we defined areas of the park that can be considered climate-change refugia, and confirmed this using satellite images taken during the dry and rainy seasons,” Godoy-Veiga said.

“We compared the images to construct a vegetation index, which clearly showed that the presumed climate-change refugia were the least seasonal areas of the park, where most of the trees don’t lose their leaves. These areas are associated with lower terrain and deeper soil, or are near rocky outcrops and the Peruaçu River.”

Located in Brazil’s central region in a transition zone between two important biomes, Cerrado (savanna) and Caatinga (semi-arid shrubland and thorn forest), Peruaçu Caves National Park is a monumental karst landscape with huge caves and speleothems (stalactites, stalagmites and other mineral formations) created over thousands of years by rainwater and the Peruaçu, a tributary of the São Francisco.

Besides caves, the park has almost 600 square kilometers of dry forest, where the study was conducted. “Analyzing only the park’s non-degraded portions, which correspond to about 80% of the total area, we concluded that almost a quarter, or more than 100 square kilometers, could be held to contain climate-change refugia,” Godoy-Veiga said.

The various factors mentioned have created a microenvironment that is sheltered from the region’s prevailing climate, providing more favorable conditions for land management and increasing the likelihood of its success.

However, this horizon should be considered soberly without exaggerated expectations as it is already clear that extreme weather such as the phenomena caused by El Niño in 1997 has adverse effects on tree growth even in refugia. “The study is a major advance in the identification of climate-change refugia even in dry forest areas such as those located in northern Minas Gerais, but despite protection from rising temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns in these refugia, the trees there are vulnerable to extreme weather,” Locosselli said.

Ceccantini agreed. “Large numbers of trees have died in recent years and are still standing in the park. The study helps us understand why and how we need to react in order to conserve this natural heritage,” he said.

“Understanding how climate affects trees on a microscale helps design strategies to take better care of trees, not just in conservation units such as national and state parks, but also in urban areas, where trees play a very important role in enhancing the quality of life for the inhabitants.”

INFORMATION:

About São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. FAPESP is aware that the very best research can only be done by working with the best researchers internationally. Therefore, it has established partnerships with funding agencies, higher education, private companies, and research organizations in other countries known for the quality of their research and has been encouraging scientists funded by its grants to further develop their international collaboration. You can learn more about FAPESP at http://www.fapesp.br/en and visit FAPESP news agency at http://www.agencia.fapesp.br/en to keep updated with the latest scientific breakthroughs FAPESP helps achieve through its many programs, awards and research centers. You may also subscribe to FAPESP news agency at http://agencia.fapesp.br/subscribe.

A mathematical model which can predict landslides that occur unexpectantly has been developed by two University of Melbourne scientists, with colleagues from GroundProbe-Orica and the University of Florence.

Professors Antoinette Tordesillas and Robin Batterham led the work over five years to develop and test the model SSSAFE (Spatiotemporal Slope Stability Analytics for Failure Estimation), which analyses slope stability over time to predict where and when a landslide or avalanche is likely to occur.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, ...

Annapolis, MD; May 26, 2021--A new study has mounted perhaps the most intricate, detailed look ever at the diversity in structure and form of bees, offering new insights in a long-standing debate over how complex social behaviors arose in certain branches of bees' evolutionary tree.

Published today in Insect Systematics and Diversity, the report is built on an analysis of nearly 300 morphological traits in bees, how those traits vary across numerous species, and what the variations suggest about the evolutionary relations between bee species. The result offers strong evidence that complex social behavior developed just once in pollen-carrying bees, rather than twice or more, separately, in different evolutionary branches--but ...

Travelling elephants pay close attention to scent trails of dung and urine left by other elephants, new research shows.

Scientists monitored well-used pathways and found that wild African savannah elephants - especially those travelling alone - were "highly attentive", sniffing and tracking the trail with their trunks.

This suggests these scents act as a "public information resource", according to researchers from the University of Exeter and Elephants for Africa.

More research is now needed to find out whether humans can create artificial elephant trails to divert elephants away from farms and villages, where conflict with humans can cause devastation to communities.

Alternatively, scent trails could be placed to improve the efficiency of routes ...

HOUSTON - Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have discovered a novel function for the metabolic enzyme medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) in glioblastoma (GBM). MCAD prevents toxic lipid buildup, in addition to its normal role in energy production, so targeting MCAD causes irreversible damage and cell death specifically in cancer cells.

The study was published today in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. Preclinical findings reveal an important new understanding of metabolism in GBM and support the development of MCAD inhibitors as a novel treatment strategy. The researchers currently are working to develop targeted therapies against the enzyme.

"With ...

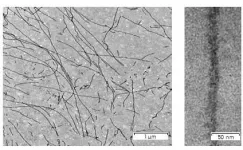

Alzheimer's disease is the most common neurodegenerative disorder in which neurons gradually die off, leading to dementia. The exact mechanism and causes of this disorder have not yet been identified. However, it is known that amyloid plaques form in the brains of patients. Plaques consist of amyloid fibrils, which are special filamentous assemblies formed by amyloid proteins.

'The number of patients with neurodegenerative disorders will continue to grow in the future. Thanks to the success of humanity in the treatment of cancer and cardiovascular diseases, more and more people are living into their 80s. At this age, the risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease, becomes very high. Unfortunately, no cures for these diseases have yet ...

Killer flies can reach accelerations of over 3g when aerial diving to catch their prey - but at such high speeds they often miss because they can't correct their course.

These are the findings of a study by researchers at the Universities of Cambridge, Lincoln, and Minnesota, published today in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Killer flies (Coenosia attenuata) perform high-speed aerial dives to attack prey flying beneath them, reaching impressive accelerations of up to 36 m/s2, equivalent to 3.6 times the acceleration due to gravity (or 3.6g). This happens because they beat their wings as they fall, combining the acceleration of powered flight with the acceleration of gravity.

This is an impressive feat: diving Falcons, the fastest animals that predate ...

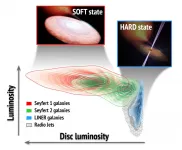

The researchers Juan A. Fernández-Ontiveros, of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) in Rome and Teo Muñoz-Darias, of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), have written an article in which they describe the different states of activity of a large sample of supermassive black holes in the centres of galaxies. They have classified them using the behaviour of their closest "relations", the stellar mass black holes in X-ray binaries. The article has just been published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS).

Black holes range in mass from objects which have only a few ...

Mercury pollution is an issue of global concern due to its toxic effects. High levels have already been measured in Arctic organisms - with worrying effects on ecosystems and the food chain. So far, the Greenland Ice Sheet has not been taken into account as a part of the Arctic mercury cycle. Now, researchers led by Jon Hawkings of the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam and Florida State University show that meltwaters in the southwest of Greenland transport considerable amounts of mercury into the Arctic Ocean. Due to the large quantities detected, the researchers assume that they are of geological origin. They present their measurements in the current issue of Nature Geoscience.

Mercury: poison for humans and the environment - ...

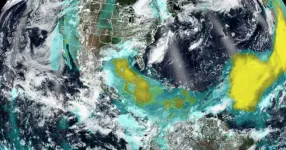

LAWRENCE -- For two weeks in June 2020, a massive dust plume from Saharan Africa crept westward across the Atlantic, blanketing the Caribbean and Gulf Coast states in the U.S. The dust storm was so strong, it earned the nickname "Godzilla."

Now, researchers from the University of Kansas have published a new study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society parsing the mechanism that transported the dust. Their results explain a phenomenon that could occur more frequently in the years ahead due to climate change, affecting human health and transportation systems.

African dust darkened the skies of the Caribbean and American Gulf States thanks to a trio of atmospheric patterns, ...

Mitochondria are the cell's power plants and produce the majority of a cell's energy needs through an electrochemical process called electron transport chain coupled to another process known as oxidative phosphorylation. A number of different proteins in mitochondria facilitate these processes, but it's not fully understood how these proteins are arranged inside mitochondria and the factors that can influence their arrangement.

Now, scientists at the University of Copenhagen have used state-of-the-art proteomics technology to shine new light on how mitochondrial proteins gather into electron transport chain complexes, and further into so-called supercomplexes. The research, which is published in Cell Reports, also examined ...