(Press-News.org) New York, NY--June 23, 2021--A challenging frontier in science and engineering is controlling matter outside of thermodynamic equilibrium to build material systems with capabilities that rival those of living organisms. Research on active colloids aims to create micro- and nanoscale "particles" that swim through viscous fluids like primitive microorganisms. When these self-propelled particles come together, they can organize and move like schools of fish to perform robotic functions, such as navigating complex environments and delivering "cargo" to targeted locations.

A Columbia Engineering team led by Kyle Bishop, professor of chemical engineering, is at the forefront of studying and designing the dynamics of active colloids powered by chemical reactions or by external magnetic, electric, or acoustic fields. The group is developing colloidal robots, in which active components interact and assemble to perform dynamic functions inspired by living cells.

In a new study published today by Physical Review Letters, Bishop's group, working with collaborators at Northwestern University's Center for Bio-Inspired Energy Science (CBES), report that they have demonstrated the use of DC electric fields to drive back-and-forth rotation of micro-particles in electric boundary layers. These particle oscillators could be useful as clocks that coordinate the organization of active matter and even, perhaps, orchestrate the functions of micron-scale robots.

"Tiny particle oscillators could enable new types of active matter that combine the swarming behaviors of self-propelled colloids and the synchronizing behaviors of coupled oscillators," says Bishop. "We expect interactions among the particles to depend on their respective positions and phases, thus enabling richer collective behaviors--behaviors that can be designed and exploited for applications in swarm robotics."

Making a reliable clock at the micron-scale is not as simple as it may sound. As one can imagine, pendulum clocks don't work well when immersed in honey. Their periodic motion--like that of all inertial oscillators--drags to a halt under sufficient resistance from friction. Without the help of inertia, it is similarly challenging to drive the oscillatory motion of micron-scale particles in viscous fluids.

"Our recent observation of colloidal spheres oscillating back and forth in a DC electric field presented a bit of mystery, one we wanted to solve," observes the paper's lead author, Zhengyan Zhang, a PhD student in Bishop's lab who discovered this effect. "By varying the particle size, field strength, and fluid conductivity, we identified experimental conditions needed for oscillations and uncovered the mechanism underlying the particles' rhythmic dynamics."

Earlier work has demonstrated how similar particles can rotate steadily by a process known as Quincke rotation. Like a water wheel filled from above, the Quincke instability is driven by the accumulation of electric charge on the particle surface and its mechanical rotation in the electric field. However, existing models of Quincke rotation--and of overdamped water wheels--do not predict oscillatory dynamics.

This new study characterizes and explains the "mysterious" oscillations by reference to a boundary layer in the nonpolar electrolyte. Within this layer, often ignored by researchers, charge carriers are generated and then migrate away under the influence of the electric field. These processes introduce spatial asymmetries in the rates of charge accumulation at the particle surface. Like a water wheel whose buckets leak faster at the top than at the bottom, asymmetric charging can lead to back-and-forth rotation at high field strengths.

"The limited generation rate of charges in these weak electrolytes creates a boundary layer comparable to the size of particle under a strong electric field, as found numerically by my PhD student Hang Yuan, a co-author of the work. As a result, the 'conductivity' of ions around particles that are within the large boundary layer is not constant, leading to the observed oscillations at strong electric fields," says Monica Olvera de la Cruz, Lawyer Taylor Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Chemistry and (by courtesy) Chemical and Biological Engineering, Physics and Astronomy at Northwestern Engineering.

"This work shows a way to generate oscillators, which could lead to the emergence of cooperative phenomena in fluids," she adds.

The team experimented with different shapes of particles and found they could generate oscillations with any particles, provided that their size was comparable to that of the boundary layer.

"By tuning the field strength and/or the electrolyte, we can predictably control the frequency of these `Quincke clocks,'" Bishop adds. "Our paper enables the design of new forms of active matter based on collections of mobile oscillators."

The team is currently studying the collective behaviors that emerge when many Quincke oscillators move and interact with one another.

INFORMATION:

About the Study

The study is titled "Quincke oscillations of colloids at planar electrodes."

Journal: Physical Review Letters.

Authors are: Zhengyan Zhang, 1 Hang Yuan, 2 Yong Dou, 1 Monica Olvera de la Cruz, 3, 2 and Kyle J. M. Bishop 1

1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Columbia University

2 Applied Physics Program, Northwestern University

3 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University

This work was supported as part of the Center for Bio-Inspired Energy Science, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Award DE-SC0000989.

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

LINKS:

URL: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.258001

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.258001

http://engineering.columbia.edu/

https://www.engineering.columbia.edu/faculty/kyle-bishop

https://cheme.columbia.edu/

https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.258001

https://cbes.northwestern.edu

https://bishop.cheme.columbia.edu/

https://www.mccormick.northwestern.edu/research-faculty/directory/profiles/olvera-de-la-cruz-monica.html

https://www.mccormick.northwestern.edu/

Columbia Engineering

Columbia Engineering, based in New York City, is one of the top engineering schools in the U.S. and one of the oldest in the nation. Also known as The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School expands knowledge and advances technology through the pioneering research of its more than 220 faculty, while educating undergraduate and graduate students in a collaborative environment to become leaders informed by a firm foundation in engineering. The School's faculty are at the center of the University's cross-disciplinary research, contributing to the Data Science Institute, Earth Institute, Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, Precision Medicine Initiative, and the Columbia Nano Initiative. Guided by its strategic vision, "Columbia Engineering for Humanity," the School aims to translate ideas into innovations that foster a sustainable, healthy, secure, connected, and creative humanity.

A new study published in Nature Communications finds that piles of sand grains, even when undisturbed, are in constant motion. Using highly-sensitive optical interference data, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Vanderbilt University present results that challenge existing theories in both geology and physics about how soils and other types of disordered materials behave.

Most people only become aware of soil movement on hillsides when soil suddenly loses its rigidity, a phenomenon known as yield. "Say that you have soil on a hillside. Then, if there's an earthquake or it rains, this material that's apparently ...

WHAT:

National Institutes of Health scientists and their collaborators have identified an internal communication network in mammals that may regulate tissue repair and inflammation, providing new insights on how diseases such as obesity and inflammatory skin disorders develop. The new research is published in Cell.

The billions of organisms living on body surfaces such as the skin of mammals--collectively called microbiota--communicate with each other and the host immune system in a sophisticated network. According to the study, viruses integrated in the host genome, remnants of previous infections called endogenous retroviruses, can control how the host immune system and the microbiota ...

Beekeepers across the United States lost 45.5% of their managed honey bee colonies from April 2020 to April 2021, according to preliminary results of the 15th annual nationwide survey conducted by the nonprofit Bee Informed Partnership (BIP). These losses mark the second highest loss rate the survey has recorded since it began in 2006 (6.1 percentage points higher than the average annual loss rate of 39.4%). The survey results highlight the continuing high rates of honey bee colony turnover. The high loss rate was driven by both elevated summer and winter losses this year, with no clear progression toward improvement ...

Those with power, such as the wealthy are more likely to blame others for having shortcomings and they are also less troubled by reports of inequality, according to recent research from the University of California San Diego's Rady School of Management.

The study published in END ...

BROOKLYN, New York, Wednesday, June 23, 2021 -- Owing to their tunable properties, hydrogels comprising stimuli-sensitive polymers are among the most appealing molecular scaffolds because their versatility allows for applications in tissue engineering, drug delivery and other biomedical fields.

Peptides and proteins are increasingly popular as building blocks because they can be stimulated to self-assemble into nanostructures such as nanoparticles or nanofibers, which enables gelation -- the formation of supramolecular hydrogels that can trap water and small molecules. Engineers, to generate such smart biomaterials, are developing systems that can respond to a multitude of stimuli including heat. Although thermosensitive hydrogels are among widely ...

Irvine, CA - June 23, 2021 - A new University of California, Irvine-led study finds that the persistence of a marker of chronic cellular stress, previously associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), also takes place in the brains of Huntington's disease (HD) patients.

Chronic cellular stress results in the abnormal accumulation of stress granules (SGs), which are clumps of protein and RNAs that gather in the cell. Prior to this study, published in the Journal of Clinical ...

Boston, MA--Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, many African leaders implemented prevention measures such as lockdowns, travel bans, border closures, and school closures. While these efforts may have helped slow the spread of the virus on the continent and continue to be important for its containment, they inadvertently disrupted livelihoods and food systems and curtailed access to critical nutrition, health, and education services. A new series of studies by researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and colleagues from the Africa Research, Implementation Science and Education (ARISE) Network finds that these disruptions may have serious ...

AMES, Iowa -- A new study of small Iowa towns found that vulnerable populations within those communities face significantly more public health risks than statewide averages.

The study, published this week in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed open access journal, was led by Benjamin Shirtcliff, associate professor of landscape architecture at Iowa State University.

He focused on three Iowa towns - Marshalltown, Ottumwa and Perry - as a proxy for studying shifting populations in rural small towns, in particular how vulnerable populations in these towns ...

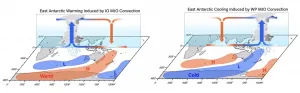

Our planet is warming due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions; but the warming differs from region to region, and it can also vary seasonally. Over the last four decades scientists have observed a persistent austral summer cooling on the eastern side of Antarctica. This puzzling feature has received world-wide attention, because it is not far away from one of the well-known global warming hotspots - the Antarctic Peninsula.

A new study published in the journal Science Advances by a team of scientists from the IBS Center for Climate Physics at Pusan National University in South Korea, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, Ewha Womans University, and National Taiwan ...

A new study from archaeologists at University of Sydney and Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, has provided important new evidence to answer the question "Who exactly were the Anglo-Saxons?"

New findings based on studying skeletal remains clearly indicates the Anglo-Saxons were a melting pot of people from both migrant and local cultural groups and not one homogenous group from Western Europe.

Professor Keith Dobney at the University of Sydney said the team's results indicate that "the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of early Medieval Britain were strikingly similar to contemporary Britain - full of people of different ancestries sharing a common language and culture".

The Anglo-Saxon (or early medieval) period in England runs from the 5th-11th centuries AD. Early Anglo-Saxon dates from ...