Hot nights confuse circadian clocks in rice, hurting crop yields

2021-06-29

(Press-News.org) Rising nighttime temperatures are curbing crop yields for rice, and new research moves us closer to understanding why. The study found that warmer nights alter the rice plant's biological schedule, with hundreds of genes being expressed earlier than usual, while hundreds of other genes are being expressed later than usual.

"Essentially, we found that warmer nights throw the rice plant's internal clock out of whack," says Colleen Doherty, an associate professor of biochemistry at North Carolina State University and corresponding author of a paper on the work.

"Most people think plants aren't dynamic, but they are. Plants are constantly regulating their biological processes - gearing up for photosynthesis just before dawn, winding that down in the late afternoon, determining precisely how and where to burn their energy resources. Plants are busy, it's just difficult to observe all that activity from the outside."

And what researchers have learned is that the clock responsible for regulating all of that activity gets messed up when the nights get hotter relative to the days.

"We already knew that climate change is leading to increased temperatures globally, and that nighttime temperatures are rising faster than daytime temperatures," Doherty says. "We also knew that warmer nights hurt rice production. But until now, we had very little insight into why warmer nights are bad for rice.

"We still don't know all the details, but we're narrowing down where to look."

Research that addresses rice yield losses is important because rice is an essential crop for feeding hundreds of millions of people each year - and because a changing climate poses challenges for global food security.

To better understand how warm nights affects rice, Doherty worked with an international team of researchers - including Krishna Jagadish of Kansas State University and Lovely Lawas of the International Rice Research Institute - to study the problem in the field. The researchers established two study sites in the Philippines. Temperatures were manipulated in different areas of each study site using either ceramic heaters or heat tents.

A research team led by Jagadish used the ceramic heaters to maintain experimental plots at 2 degrees Celsius above the ambient temperature, and took samples from the rice plants every three hours for 24 hours. Control plots were not heated, but were also sampled every three hours during the same 24-hour period. These tests were repeated four times. The heat tents were later used to validate the results from the ceramic heater tests.

Meanwhile, a team led by Doherty found that more than a thousand genes were being expressed at the "wrong" time when nighttime temperatures were higher. Specifically, hotter nights resulted in hundreds of genes - including many associated with photosynthesis - becoming active later in the day. Meanwhile, hundreds of other genes were becoming active much earlier in the evening than normal, disrupting the finely tuned timing necessary for optimal yield.

"It's not clear what all of these genes do, but it is clear that these conflicting schedule shifts are not good for the plant," Doherty says.

The researchers found that many of the affected genes are regulated by 24 other genes, called transcription factors. Of those 24, four of the transcription factors were deemed most promising for future study.

"We need to do additional work to figure out exactly what's happening here, so that we can begin breeding rice that's resilient against warmer nights," Doherty says. "Rice is an important food crop. And other staple crops are also affected by hotter nights - including wheat. This isn't just an interesting scientific question, it's a global food security issue."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Warm Nights Disrupt Global Transcriptional Rhythms in Field-Grown Rice Panicles," is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. First author of the paper is Jigar Desai, a former Ph.D. student at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Lawas; Jagadish; Ashlee Valente and Adam Leman of Mimetics LLC; and Dmitry Grinevich, another former Ph.D. student at NC State.

The work was done with support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture under National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) grant 2015-67013-22814 and NIFA project 1002035.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-29

A recent proof-of-concept study finds that a low-cost training program can reduce hazardous driving in older adults. Researchers hope the finding will lead to the training becoming more widely available.

"On-road training and simulator training programs have been successful at reducing car accidents involving older drivers - with benefits lasting for years after the training," says Jing Yuan, first author of the study and a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University. "However, many older adults are unlikely to have access to these training programs or technologies."

"We developed a training program, ...

2021-06-29

Populations of Drosophila suzukii fruit flies - so-called "spotted-wing Drosophila" that devastate soft-skinned fruit in North America, Europe and parts of South America - could be greatly suppressed with the introduction of genetically modified D. suzukii flies that produce only males after mating, according to new research from North Carolina State University.

D. suzukii are modified with a female-lethal gene that uses a common antibiotic as an off switch. Withholding the antibiotic tetracycline in the diet of larvae essentially eliminates birth of female D. suzukii flies as the modified male flies successfully mate with females, says Max Scott, an NC State entomologist who is the corresponding author of a paper describing the research.

"We use a genetic female-lethal system - a ...

2021-06-29

Researchers from the Laboratory of Oncolytic-Virus-Immuno-Therapeutics (LOVIT) at the LIH Department of Oncology (DONC) are working on the development of novel anticancer strategies based on oncolytic viruses, "good" viruses that can specifically infect, replicate in and kill cancer cells. In particular, the LOVIT team elucidated the mechanism through which the H-1PV cancer-destroying virus can attach to and enter cancer cells, thereby causing their lysis and death. At the heart of this process lie laminins, and specifically laminin γ1, a family of proteins on the surface of a cancer cell to which this virus binds, and which therefore act as the 'door' through which the virus enters the cells. The findings, which were published in the prestigious ...

2021-06-29

Beetles are creatures with built-in body armor. They are tiny tanks covered with hard shells, also known as exoskeletons, protecting their soft, skeleton-less bodies inside. In addition to providing armored protection, the beetle's exoskeleton offers functions like sensory feedback and hydration control. Notably, the exoskeletons of many beetles are also brilliantly colored and patterned, which enhances visual communication with other beetles and organisms.

Ling Li, lead investigator and assistant professor in mechanical engineering, has joined colleagues from six other universities to investigate the interplay between mechanical and optical performance ...

2021-06-29

Globally, more than 400 million people have diabetes, most of them suffering from type 2 diabetes.

Before the onset of actual type 2 diabetes, people are often diagnosed with abnormalities in glucose metabolism that are milder than those associated with diabetes. The term used to indicate such cases is prediabetes. Roughly 5-10% of people with prediabetes develop type 2 diabetes within a year-long follow-up.

Insulin resistance in muscle tissue is one of the earliest metabolic abnormalities detected in individuals who are developing type 2 diabetes, and the phenomenon is already seen in prediabetes.

In a collaborative study, researchers from the University of Helsinki, the ...

2021-06-29

URBANA, Ill. - Despite soybean's high protein and oil content and its potential to boost food security on the continent, Africa produces less than 1% of the world's soybean crop. Production lags, in part, because most soybean cultivars are bred for North and South American conditions that don't match African environments.

Researchers from the Soybean Innovation Lab (SIL), a U.S. Agency for International Development-funded project led by the University of Illinois, are working to change that. In a new study, published in Agronomy, they have developed methods to help breeders improve soybean cultivars specifically for African environments, with the intention of creating fast-maturing ...

2021-06-29

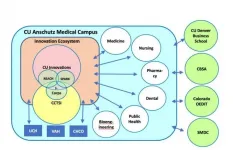

A new study highlights the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus as an example of how an academic medical center can turn groundbreaking research into commercial products that improve patient care and public health.

The paper, published recently in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, focuses on the unique ecosystem at CU Anschutz responsible for these innovations. And it specifically details the campus's collaborative culture and how biomedical research is commercialized.

The campus has successfully turned academic research into a variety of products. CU Anschutz, for example, developed two vaccines for shingles, Zostavax and Shingrix, and ...

2021-06-29

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Biodegradable plastics are supposed to be good for the environment. But because they are specifically made to degrade quickly, they cannot be recycled.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand have developed a method to turn biodegradable plastic knives, spoons, and forks into a foam that can be used as insulation in walls or in flotation devices.

The investigators placed the cutlery, which was previously thought to be "nonfoamable" plastic, into a chamber filled with carbon dioxide. ...

2021-06-29

The death of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was caused by the impact of a huge asteroid on the Earth. However, palaeontologists have continued to debate whether they were already in decline or not before the impact.

In a new study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of scientists, which includes the University of Bristol, show that they were already in decline for as much as ten million years before the final death blow.

Lead author, Fabien Condamine, a CNRS researcher from the Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution de Montpellier (France), said: "We looked at the six most abundant dinosaur families through the whole of the Cretaceous, spanning from 150 to 66 million ...

2021-06-29

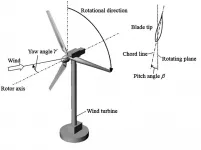

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- As wind passes through a turbine, it creates a wake that decreases the downstream average wind velocity. The faster the spin of the turbine blades relative to the wind speed, the greater the impact on the downstream wake profile.

For wind farms, it is important to control upstream turbines in an efficient manner so downstream turbines are not adversely affected by upstream wake effects. In the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign show by designing controllers based on viewing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Hot nights confuse circadian clocks in rice, hurting crop yields