(Press-News.org) The oil industry, pharmaceutical companies and bioreactor manufacturers all face one common enemy: bubbles. Bubbles can form during the manufacturing or transport of various liquids, and their formation and rupture can cause significant issues in product quality.

Inspired by these issues and the puzzling physics behind bubbles, an international scientific collaboration was born. Stanford University chemical engineer Gerald Fuller along with his PhD students Aadithya Kannan and Vinny Chandran Suja, as well as visiting PhD student Daniele Tammaro from the University of Naples, teamed up to study how different kinds of bubbles pop.

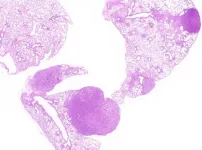

The researchers were particularly interested in bubbles with proteins embedded on their surfaces, which is a common occurrence in the pharmaceutical industry and in bioreactors used for cell culture. In an unanticipated result, the researchers discovered that the protein bubbles they were studying opened up like flowers when popped with a needle. Their findings are detailed in a study published in the journal of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on July 19.

"What really strikes me is that even after all these years of research, bubble physics keeps surprising us with unexpectedly beautiful phenomena," Suja said.

Bursting the bubble

Bubbles can pop in a variety of ways, depending on their physical and chemical properties. One important property is called viscoelasticity.

"Most materials that surround us are actually not perfectly liquid like water or olive oil. They're not perfectly elastic either, like a pencil eraser. They're somewhere in between," explained Fuller, who is the Fletcher Jones II Professor in the School of Engineering and co-led the study with Professor Pier Luca Maffettone from the University of Naples.

This "in-between" state is called viscoelasticity, and the researchers found that, unlike conventional soap bubbles, viscoelastic bubbles that have both liquid- and solid-like properties deform and pop in shapes that mimic a blooming flower.

But as Tammaro notes, "With our eyes it's not possible to see how the hole opens up when a bubble pops, so we just see a bubble that vanishes."

So the researchers used high-speed cameras operating at 20,000 frames per second, over 300 times faster than a human eye, to capture and study the phenomenon.

"While working on my thesis on bubble coalescence in biologic drug formulations, I decided to look at bubble rupture through a high-speed camera that we had in our lab," Kannan said. "When we did that, we saw that this bubble, which had proteins at its surface, actually exhibited a very different mechanism of rupture compared to what we traditionally expect."

In the lab, the researchers soaked a metal ring in a solution of proteins with viscoelastic properties. They then carefully inflated bubbles on this ring using a highly controlled flow of air. Once the bubbles were large enough, they made contact with a suspended needle and popped.

As the video shows, when the bubbles reach the needle, the surface peels away like petals. This peeling happens because the viscoelastic properties at the surface allow the solution to have more solid-like characteristics than common soap bubbles. Kannan likened this special bubble bursting to a popping balloon, which also peels away like a flower.

Investigating bubble physics

Once the flowering phenomenon had been sufficiently observed, the researchers began to develop analytical models of the popping. Using current knowledge of bubble dynamics and mathematical models, the team presented a set of promising computational reproductions of the bubble flowering in their paper.

By studying bubble formation and bursting, the team hopes to eventually learn how to reduce bubble generation and popping in real-world applications. They predict that their findings will have applications in fields from medicine and vaccine production to oil transportation.

"It is really important to see how generalizable this is, and how the flowering is different for other systems," Kannan concluded.

INFORMATION:

New research has found marine seismic surveys used in oil and gas exploration are not impacting the abundance or behaviour of commercially valuable fishes in the tropical shelf environment in north-western Australia.

The research is the first of its kind to use dedicated seismic vessels to measure the impacts of the survey's noise in an ocean environment, with the eight-month experiment conducted within a 2500 square kilometre fishery management zone near the Pilbara coast.

It involved using multiple acoustic sensors, tagging 387 red emperor fish and deploying more than ...

KRAS was one of the first oncogenes to be identified, a few decades ago. It is among the most common drivers of cancer and its mutations can be detected in around 25 per cent of human tumours. The development of KRAS inhibitors is, thus, an extremely active line of research. Effective results have been elusive so far, though - no KRAS inhibitor had been available until a month ago, when the FDA granted approval to Sotorasib.

KRAS encodes two gene products, KRAS4A and KRAS4B, whose levels can vary across organs and embryonic stages. When KRAS mutates, both variants, or isoforms, are activated. Though, some studies have focussed on approaches to target only KRAS4B, since it usually found to be expressed at ...

Evidence shows that early detection and treatment of cancer can significantly improve health outcomes, however women in Mississippi, particularly in underserved populations, experience the worst health outcomes for cervical, breast, and oropharyngeal cancer. ...

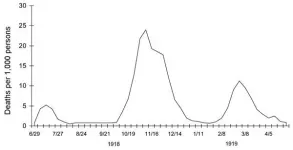

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic there have been countless comparisons to the 1918 influenza pandemic in terms of overall medical impact. Many of the comparisons addressed overall cases which, given the lack of a confirmatory lab test in 1918 and no meaningful case definitions for both pandemics, make such comparisons patently invalid. Overall mortality comparisons, although methodologically flawed as well, do offer a reasonably comparative outcome measure and offers a greater degree of validity. This measure is further enhanced when adjusted for population and average life years lost (see accompanying table for mortality comparisons ...

Researchers at Michigan Medicine have discovered yet another functional autoantibody in COVID-19 patients that contributes to the disease's development and the "firestorm" of blood clots and inflammation it induces.

A growing body of studies suggests COVID-19 emulates many aspects of systemic autoimmune disorders, including the release of a flurry of overactive immune cells that produce toxic webs of proteins and DNA called neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs.

For this study, the team analyzed serum from over 300 hospitalized COVID patients, searching for a novel autoantibody that shields the toxic NETs from being destroyed and produces a lasting ...

The link between on-road traffic and air pollution is well-known, as are the negative health impacts of pollution exposure. However, the many factors that may influence commuters' exposure to pollutants - such as frequency, time, and duration of commute - and the overall impact of commuting remains a matter of on-going scientific discovery.

Dr. Jenna Krall, assistant professor at the George Mason University College of Health and Human Services, is using statistical methods to better understand exposure to air pollution. Krall studies how commuting patterns impact exposure to fine particulate matter ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Tens of millions of patients around the world suffer from persistent and potentially life-threatening wounds. These chronic wounds, which are also a leading cause of amputation, have treatments, but the cost of existing wound dressings can prevent them from reaching people in need.

Now, a Michigan State University researcher is leading an international team of scientists to develop a low-cost, practical biopolymer dressing that helps heal these wounds.

"The existing efficient technologies are far too expensive for most health care systems, ...

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) launched a new online tool that could more quickly advance medical discoveries to reverse progressive hearing loss. The tool enables easy access to genetic and other molecular data from hundreds of technical research studies involving hearing function and the ear. The research portal called gene Expression Analysis Resource (gEAR) was unveiled in a study last month in Nature Methods. It is operated by a group of physician-scientists at the UMSOM Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS) in collaboration with their colleagues at other institutions.

The portal allows researchers to rapidly access data and provides easily interpreted visualizations of datasets. Scientists can also input ...

New Curtin University-led research has called into question existing health advice that mothers wait a minimum of two years after giving birth to become pregnant again, in order to reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm and small-for-gestational age births.

The research found that a World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation to wait at least 24 months to conceive after a previous birth may be unnecessarily long for mothers in high-income countries such as Australia, Finland, Norway and the United States.

Lead researcher ...

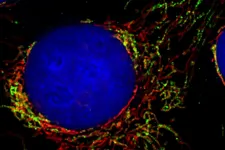

Errors in the metabolic processes of mitochondria are responsible for a variety of diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Scientists needed to find out just how the necessary building blocks are imported into the complex biochemical apparatus of these cell areas. The TOM complex (translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane) is considered the gateway to the mitochondrion, the proverbial powerhouse of the cell. The working group headed by Professor Chris Meisinger at the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Freiburg has now demonstrated - in human cells - how signaling molecules control this gate. A signaling protein called DYRK1A modifies the molecular machinery of TOM and makes it more permeable ...