(Press-News.org) Beetles are champions at surviving in extremely dry environments. In part, this property is due to their ability to suck water from the air with their rear ends. A new collaborative study by researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the University of Edinburgh explains just how. Beyond helping to explain how beetles thrive in environments where few other animals can survive, the knowledge could eventually be used for more targeted and delicate control of global pests such as the grain weevil and red flour beetle.

Insect pests eat their way through thousands of tons of food around the world every year. Food security in developing nations is particularly affected by animal species like the grain weevil and red flour beetle which have specialized in surviving in extremely dry environments, granaries included, for thousands of years.

In a new study, researchers at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Biology investigated the molecular and physiological processes underlying the ability of beetles to survive their entire lives without drinking any liquid water whatsoever. One of the secrets of this characteristic is found in their rear ends.

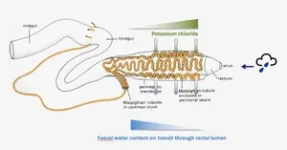

Indeed, beetles can open their rectums and take up water from moist air and convert it into fluid, which they can then absorb into their bodies. This novel approach to consuming water has been known for more than a century within scientific circles around the world, but never fully clarified until now.

"We have shed new light on the molecular mechanisms that allow beetles to absorb water rectally. Insects are particularly sensitive to changes in their water balance. As such, this knowledge can be used to develop more targeted methods to combat beetle species which destroy our food production, without killing other animals or harming humans and nature," says Associate Professor Kenneth Veland Halberg of the Department of Biology, who led the research.

Bone dry stool testifies to effective fluid extraction

The researchers studied the internal organs of red flour beetles to learn more about their ability to absorb water through the rectum. Red flour beetles are used as so-called model organisms, which means that they are offer tools that make them easy to work with and that their biology is similar to that found in other beetles.

Here, the researchers identified a gene that is expressed sixty times more in the beetle's rectum compared to the rest of the animal, which is higher than any other gene they found. This led them to a unique group of cells known as leptophragmata cells. Upon closer inspection, they could see that these cells play a crucial role when the beetle absorbs water through its rear end.

"Leptophragmata cells are tiny cells situated like windows between the beetle's kidneys and the insect circulatory system, or blood. As the beetle's kidneys encircle its hindgut, the leptophragmata cells function by pumping salts into the kidneys so that they are able to harvest water from moist air through their rectums and from here into their bodies. The gene we have discovered is essential to this process, which is new knowledge for us," explains Kenneth Veland Halberg.

Besides being able to suck water out of the air, beetles are also extremely effective at extracting liquid from food. Even dry grain, which may consist of 1-2 percent water, can contribute to a beetle’s fluid balance.

"A beetle can go through an entire life cycle without drinking liquid water. This is because of their modified rectum and closely applied kidneys, which together make a multi-organ system that is highly specialized in extracting water from the food that they eat and from the air around them. In fact, it happens so effectively that the stool samples we have examined were completely dry and without any trace of water," explains Kenneth Veland Halberg.

25 percent global food production is lost

Over the past 500 million years, beetles have successfully spread across the planet. Today, one in five animal species on Earth is a beetle. Unfortunately, beetles are also among the pests that have a devastating impact on our food security. The red flour beetle, grain weevil, confused flour beetle, Colorado potato beetle and other types of beetles make their way into up to 25 percent of the global food supply every year.

We use approximately $100 billion in pesticides worldwide every year to keep insects out of our food. However, traditional pesticides harm other living organisms and destroy the environment.

Therefore, according to Kenneth Veland Halberg, it is important to develop more specific and ‘eco-friendly’ insecticides, which only targets insect pests while leaving more beneficial insects, such as bees, alone. This is where a new and better understanding of beetles’ anatomy and physiology could become key.

"Now we understand exactly which genes, cells and molecules are at play in the beetle when it absorbs water in its rectum. This means that we suddenly have a grip on how to disrup these very efficient processes by, for example, developing insecticides that target this function and in doing so, kill the beetle," says Kenneth Veland Halberg, who adds:

"There is twenty times as much insect biomass on Earth than that of humans. They play key roles in most food webs have a huge impact on virtually all ecosystems and on human health. So, we need to understand them better," concludes the researcher.

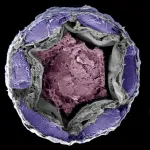

Caption: Microscopic cross-section of the beetle's hindgut. The picture shows the dry stool in magenta colors surrounded by the rectum in gray. The malpighian tubule of the beetle is seen in purple. Photo: Kenneth Veland Halberg

Facts:

About one out of every five species on Earth is a beetle. Roughly 400,000 species have been described, but it is believed that there are well over a million in total.

The researchers used the red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) as a model species for the study because it has a well-sequenced genome that allows for the use of a wide spectrum of genetic and molecular biology tools.

Grain weevils, confused flour beetles, Colorado potato beetles and other types of beetles make their way into up to 25 percent of the global food supply every year.

The problem is especially pronounced in developing countries, where access to effective pest control is limited or nonexistent.

The project was conducted in collaboration with researchers from University of Copenhagen, Denmark and University of Glasgow and University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

The study was just published in the scientific journal, PNAS.

Caption: Grain weevils are one of the most common granary pests. Photo: Getty

END

Researchers get to the “bottom” of how beetles use their butts to stay hydrated

Beetles are champions at surviving in extremely dry environments. In part, this property is due to their ability to suck water from the air with their rear ends. A new University of Copenhagen study explains just how. The knowledge could eventually be use

2023-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New MU study shapes understanding of adaptive clothing customer needs

2023-03-21

With the growth of the niche adaptive clothing market comes new challenges for retailers, including making the process of online shopping more inclusive for people with varying degrees of disability as well as expanding the functionality and aesthetic appeal of individual garments.

This study involved mining online reviews to understand the perspectives of adaptive clothing customers. University of Missouri researchers identified two main challenges for adaptive clothing consumers.

Customers said ...

Aging | Age-related methylation changes in the human sperm epigenome

2023-03-21

“[...] we identified > 1,000 candidate genes with genome-wide significant age-related methylation changes in sperm.”

BUFFALO, NY- March 21, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 5, entitled, “Age-related methylation changes in the human sperm epigenome.”

Advanced paternal age is associated with increased risks for reproductive and offspring medical problems. Accumulating evidence suggests age-related changes ...

Study finds similar association of progestogen-only and combined hormonal contraceptives with breast cancer risk

2023-03-21

There is a relative increase of 20% to 30% in breast cancer risk associated with both combined and progesterone-only contraceptives, whatever the mode of delivery, though with five years of use, the 15-year absolute excess incidence is at most 265 cases per 100,000 users. The results appear in a new study publishing March 21st in the open access journal PLOS Medicine by Kirstin Pirie of University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues.

Use of combined oral contraceptives, containing both estrogen and progestogen, has previously been associated with a small increase in breast cancer risk but there is limited data about the ...

Exercise therapy is safe, may improve quality of life for many people with heart failure

2023-03-21

CONTENT UPDATED 3/17 - note new references to cardiac rehabilitation.

Statement Highlights:

A new scientific statement indicates supervised exercise therapy may help improve symptoms for people with one of the most common types of heart failure, known as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), in which the heart muscle’s pumping strength is intact.

Exercise therapy had comparable or better results on improving exercise capacity for people with preserved EF compared to those who have heart failure with reduced ...

COVID-19 unemployment stigma is real and could threaten future job prospects: uOttawa study

2023-03-21

Regina Bateson, an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Social Science’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, details the findings of her study, which shows the significant social and economic impacts to individuals who were out of work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Below she answers questions about her study.

Question: How was this research performed?

Regina Bateson: “In this study, I conducted a pre-registered survey experiment with a nationally representative sample of 974 U.S. adults. ...

Ultra-lightweight multifunctional space skin created to withstand extreme conditions in space

2023-03-21

A new nano-barrier coating could help protect ultra-lightweight carbon composite materials from extreme conditions in space, according to a study from the University of Surrey and Airbus Defence and Space.

The new functionality added to previously developed ‘space skin’ structures adds a layer of protection to help maintain space payloads while travelling in space, similar to having its very own robust ultralight protective jacket.

The research team has shown that their innovative nano-barrier would help drastically increase the stability of carbon fibre materials, while reducing radiation ...

Researchers identify new genes that modulate the toxicity of the protein β-amyloid, responsible for causing Alzheimer’s disease

2023-03-21

An international study led by the Molecular Physiology Laboratory at the UPF Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS) identifies new genes that modulate the toxicity of the protein β-amyloid, responsible for causing Alzheimer’s disease. Combining molecular biology, genomics and bioinformatics techniques, 238 amyloid toxicity protective or activator genes have been identified. Among them, the gene Surf4 stands out. It is involved in the control of intracellular calcium and, by increasing the toxicity of the β-amyloid protein, contributes to the disease.

The research has been carried out thanks to the support ...

Smart light traps

2023-03-21

Plants use photosynthesis to harvest energy from sunlight. Now researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have applied this principle as the basis for developing new sustainable processes which in the future may produce syngas (synthetic gas) for the large-scale chemical industry and be able to charge batteries.

Syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, is an important intermediate product in the manufacture of many chemical starter materials such as ammonia, methanol and synthetic hydrocarbon fuels. "Syngas is currently made almost exclusively using fossil raw materials," ...

Visualization of electron dynamics on liquid helium for the first time

2023-03-21

An international team led by Lancaster University has discovered how electrons can slither rapidly to-and-fro across a quantum surface when driven by external forces.

The research, published in Physical Review B, has enabled the visualisation of the motion of electrons on liquid helium for the first time.

The experiments, carried out in Riken, Japan, by Kostyantyn Nasyedkin (now at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, USA) in the lab of Kimitoshi Kono (now in Taiwan at Yang Ming Chiao Tung University) detected unusual oscillations whose frequencies varied in time. Although it was unclear how ...

Argonne is helping U.S. companies advance battery recycling technology and strengthen the nation’s battery supply chain

2023-03-21

Argonne received $3.5 million in funding to help accelerate battery production in America, lower costs, provide a domestic source of materials and reduce the environmental impact of electric vehicle batteries.

Batteries are critical to powering a clean energy economy. This is especially true in the transportation sector, where electric vehicles (EVs) are on track to make up half of all new vehicle sales by 2030. In order to meet this rapidly increasing demand, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is distributing funding to advance domestic recycling and reuse of electric vehicle batteries. Managed by DOE’s Vehicle ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

New tool reveals the secrets of HIV-infected cells

HMH scientists calculate breathing-brain wave rhythms in deepest sleep

Electron microscopy shows ‘mouse bite’ defects in semiconductors

Ochsner Children's CEO joins Make-A-Wish Board

Research spotlight: Exploring the neural basis of visual imagination

Wildlife imaging shows that AI models aren’t as smart as we think

Prolonged drought linked to instability in key nitrogen-cycling microbes in Connecticut salt marsh

Self-cleaning fuel cells? Researchers reveal steam-powered fix for ‘sulfur poisoning’

Bacteria found in mouth and gut may help protect against severe peanut allergic reactions

Ultra-processed foods in preschool years associated with behavioural difficulties in childhood

A fanged frog long thought to be one species is revealing itself to be several

Weill Cornell Medicine selected for Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award

Largest high-precision 3D facial database built in China, enabling more lifelike digital humans

SwRI upgrades facilities to expand subsurface safety valve testing to new application

Iron deficiency blocks the growth of young pancreatic cells

Selective forest thinning in the eastern Cascades supports both snowpack and wildfire resilience

A sea of light: HETDEX astronomers reveal hidden structures in the young universe

Some young gamers may be at higher risk of mental health problems, but family and school support can help

Reduce rust by dumping your wok twice, and other kitchen tips

High-fat diet accelerates breast cancer tumor growth and invasion

Leveraging AI models, neuroscientists parse canary songs to better understand human speech

Ultraprocessed food consumption and behavioral outcomes in Canadian children

The ISSCR honors Dr. Kyle M. Loh with the 2026 Early Career Impact Award for Transformative Advances in Stem Cell Biology

The ISSCR honors Alexander Meissner with the 2026 ISSCR Momentum Award for exceptional work in developmental and stem cell epigenetics

The ISSCR honors stem cell COREdinates and CorEUstem with the 2026 ISSCR Public Service Award

Minimally invasive procedure effectively treats small kidney cancers

SwRI earns CMMC Level 2 cybersecurity certification

Doctors and nurses believe their own substance use affects patients

[Press-News.org] Researchers get to the “bottom” of how beetles use their butts to stay hydratedBeetles are champions at surviving in extremely dry environments. In part, this property is due to their ability to suck water from the air with their rear ends. A new University of Copenhagen study explains just how. The knowledge could eventually be use