(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. – In creating five new isotopes, an international research team working at the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, or FRIB, at Michigan State University has brought the stars closer to Earth.

The isotopes — known as thulium-182, thulium-183, ytterbium-186, ytterbium-187 and lutetium-190 — were reported Feb. 15 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

These represent the first batch of new isotopes made at FRIB, a user facility for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, or DOE-SC, supporting the mission of the DOE-SC Office of Nuclear Physics. The new isotopes show that FRIB is nearing the creation of nuclear specimens that currently only exist when ultradense celestial bodies known as neutron stars crash into each other.

“That’s the exciting part,” said Alexandra Gade, professor of physics at FRIB and in MSU’s Department of Physics and Astronomy and FRIB scientific director. “We are confident we can get even closer to those nuclei that are important for astrophysics.”

Gade is also a co-spokesperson of the project, which was led by Oleg Tarasov, senior research physicist at FRIB.

The research team included a cohort based at FRIB and MSU, along with collaborators at the Institute for Basic Science in South Korea and at RIKEN in Japan, an acronym that translates to the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research.

“This is probably the first time these isotopes have existed on the surface of the Earth,” said Bradley Sherrill, University Distinguished Professor in MSU’s College of Natural Science and head of the Advanced Rare Isotope Separator department at FRIB.

For an explanation as to what “advanced” means in this context, Sherrill said that researchers needed only a couple individual particles of a new isotope to confirm its existence and identity using FRIB’s state-of-the-art instruments.

With researchers now knowing how to make these new isotopes, they can start making them in greater quantities to conduct experiments that were never possible before. The researchers are also eager to follow the path they’ve forged to make more new isotopes that are even more like what are found in the stars.

“I like to draw the analogy of taking a journey. We’ve been looking forward to going somewhere we’ve never been before and this is the first step,” Sherrill said. “We’ve left home and we’re starting to explore.”

Almost star stuff

Our sun is a cosmic atomic factory. It’s powerful enough to take the cores of two hydrogen atoms, or nuclei, and fuse them into one helium nucleus.

Hydrogen and helium are the first and lightest entries on the periodic table of the elements. Getting to the heavier elements on the table requires even more intense environments than what’s found in the sun.

Scientists hypothesize that elements like gold — about 200 times as massive as hydrogen — are created when two neutron stars merge.

Neutron stars are the leftover cores of exploded stars that were originally much larger than our sun, but not so much larger that they can become black holes in their final acts. Although they’re not black holes, neutron stars still cram an immense amount of mass into a very modest size.

“They’re about the size of Lansing with the mass of our sun,” Sherrill said. “It’s not certain, but people think that all of the gold on Earth was made in neutron star collisions.”

By making isotopes that are present at the site of a neutron star collision, scientists could better explore and understand the processes involved in making these heavy elements.

The five new isotopes are not part of that milieu, but they are the closest scientists have come to reaching that special territory — and the outlook for finally reaching it is very good.

To create the new isotopes, the team sent a beam of platinum ions barreling into a carbon target. The beam current divided by the charge state was 50 nanoamps. Since these experiments were performed, FRIB has already scaled its beam power up to 350 nanoamps and has plans to reach up to 15,000 nanoamps.

In the meantime, the new isotopes are exciting in and of themselves, presenting the nuclear research community new opportunities to step into the unknown.

“It’s not a big surprise that these isotopes exist, but now that we have them, we have colleagues who will be very interested in what we can measure next,” Gade said. “I’m already starting to think of what we can do next in terms of measuring their half-lives, their masses and other properties.”

Researching these quantities in isotopes that have never been available before will help inform and refine our understanding of fundamental nuclear science.

“There’s so much more to learn,” Sherrill said. “And we’re on our way.”

By Matt Davenport.

Read on MSUToday.

###

Michigan State University has been advancing the common good with uncommon will for more than 165 years. One of the world's leading public research universities, MSU pushes the boundaries of discovery to make a better, safer, healthier world for all while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 400 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

Michigan State University operates the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) as a user facility for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE-SC), supporting the mission of the DOE-SC Office of Nuclear Physics. Hosting what is designed to be the most powerful heavy-ion accelerator, FRIB enables scientists to make discoveries about the properties of rare isotopes in order to better understand the physics of nuclei, nuclear astrophysics, fundamental interactions, and applications for society, including in medicine, homeland security, and industry.

The U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of today’s most pressing challenges. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

END

New nuclei can help shape our understanding of fundamental science on Earth and in the cosmos

FRIB creates 5 new isotopes

2024-02-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Searching for clues in the history book of the ocean

2024-02-15

Oxygen is fundamental to sustaining life on Earth. The ocean gets its oxygen from its uppermost layers in contact with the atmosphere. As our planet continues to warm, the ocean is gradually losing its capacity to absorb oxygen, with severe consequences on marine ecosystems and human activities that depend on them. While these trends will likely continue in the future, it remains unclear how ocean oxygen will redistribute across the ocean interior, where ocean currents and biological degradation of biomass dominate over atmospheric diffusion.

“Marine sediments are the history book of the ocean. ...

Car fumes, weeds pose double whammy for fire-loving native plants

2024-02-15

Springtime brings native wildflowers to bloom in the Santa Monica Mountains, northwest of Los Angeles. These beauties provide food for insects, maintain healthy soil and filter water seeping into the ground — in addition to offering breathtaking displays of color.

They’re also good at surviving after wildfire, having adapted to it through millennia. But new research shows wildflowers that usually would burst back after a blaze and a good rain are losing out to the long-standing, double threat of city smog and nonnative weeds.

A recent study led by Justin Valliere, assistant professor in the UC ...

How Chinese migrants in Los Angeles Chinatown gained self-reliance

2024-02-15

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States was high, as working-class laborers in the country viewed Chinese workers as a threat.

Prior research has found that during that period, approximately 400,000 Chinese migrants came to the U.S., many of whom went to California to build the Transcontinental Railroad. Following the project's completion, competition for jobs grew tougher, and passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S.

But ...

New study by researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill finds chemical composition of US air pollution changed over time

2024-02-15

A new study published in Atmospheric Environment by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill analyzed space and time trends for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the continental United States to track the progress of regulatory actions by federal, state and local authorities aimed at curbing air pollution. The team found that while the annual average concentration for PM2.5 had been significantly reduced, its chemical composition had changed during the study period of 2006 to 2020. Their analysis suggests targeted strategies to reduce specific pollutants for different regions ...

ASHG names Amanda Perl as Chief Executive Officer

2024-02-15

For Immediate Release: Thursday, February 15, 2024, 3:00pm U.S. Eastern Time

Media Contact: Kara Flynn, 202.257.8424, press@ashg.org

ROCKVILLE, MD - The American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) is excited to announce the selection of Amanda Perl as the organization’s next Chief Executive Officer. Perl has served in numerous association leadership positions with deep experience in strategic planning, membership, publishing, communications, and society operations, as well as meetings and conferences.

“ASHG is delighted to welcome Amanda, a seasoned association executive, to the team,” said ASHG President Bruce D. Gelb, MD. “We are confident ...

GV1001 reduces neurodegeneration and prolongs lifespan in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease

2024-02-15

“[...] accelerated aging and Alzheimer’s disease are closely related, and this study confirmed that GV1001 has multiple anti-aging effects.”

BUFFALO, NY- February 15, 2024 – A new research paper was published on the cover of Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 3, entitled, “GV1001 reduces neurodegeneration and prolongs lifespan in 3xTg-AD mouse model through anti-aging effects.”

GV1001, which mimics the activity of human telomerase reverse transcriptase, protects neural cells from amyloid beta (Aβ) toxicity and other stressors through ...

Study: Ablative stereotactic magnetic resonance-guided adaptive radiation therapy may improve overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer

2024-02-15

MIAMI, FL – February 15, 2024 – A study co-led by researchers at Miami Cancer Institute, part of Baptist Health South Florida, found that ablative stereotactic magnetic resonance (MR)-guided adaptive radiation therapy may improve local control (LC) and overall survival (OS) in patients with borderline resectable (BRPC) and locally advanced pancreas cancer (LAPC). Long-term outcomes from the Phase 2 SMART trial demonstrate encouraging OS and limited toxicity as published recently in Radiotherapy & Oncology (“The Green Journal”).

“Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is a leading cause of cancer death. Surgery is the only known ...

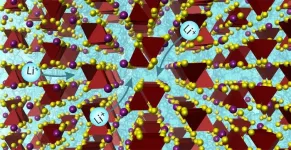

Discovery of new Li ion conductor unlocks new direction for sustainable batteries

2024-02-15

One of the grand challenges for materials science is the design and discovery of new materials that address global priorities such as Net Zero.

In a paper published in the journal Science, researchers at the University of Liverpool have discovered a solid material that rapidly conducts lithium ions. Such lithium electrolytes are essential components in the rechargeable batteries that power electric vehicles and many electronic devices.

Consisting of non-toxic earth-abundant elements, the new material has high ...

Unearthed: Why zebra go first in body-size-dependent grazing succession in the Serengeti

2024-02-15

Why do Serengeti zebra, wildebeest, and gazelle – all sharing limited food resources – follow the same migratory routes, one after another, in a body-size dependent way? This longstanding question has now been evaluated by researchers who used novel data to show how a balance of species interactions and ecological factors regulate this process. They say competition pushes zebra ahead of the wildebeest, and wildebeest then eat plants in a way that facilitates development of newer growth the trailing gazelle like. “Our results highlight a balance between facilitative and competitive forces,” the authors say. Large seasonal migrations are a ...

Oxygen increased in the tropical ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum

2024-02-15

Oxygenation in the tropical North Pacific Ocean increased during a warm climatic interval that occurred roughly 56 million years ago, despite high global temperatures, according to a new study. Its findings offer insights into how modern tropical oceans may respond to ongoing anthropogenic climate warming. The availability and distribution of dissolved oxygen in Earth’s oceans play a fundamental role in supporting marine ecosystems and marine life. However, oxygen in the global oceans is declining in response to anthropogenic warming. Although these trends writ large are predicted to continue, the future of oxygen in the highly productive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

Electric field tunes vibrations to ease heat transfer

[Press-News.org] New nuclei can help shape our understanding of fundamental science on Earth and in the cosmosFRIB creates 5 new isotopes