(Press-News.org) In the first 24 hours after a python devours its massive prey, its heart grows 25%, its cardiac tissue softens dramatically, and the organ squeezes harder and harder to more than double its pulse. Meanwhile, a vast collection of specialized genes kicks into action to help boost the snake’s metabolism fortyfold. Two weeks later, after its feast has been digested, all systems return to normal—its heart remaining just slightly larger, and even stronger, than before.

This extraordinary process, described by CU Boulder researchers this week in the journal PNAS, could ultimately inspire novel treatments for a common human heart condition called cardiac fibrosis, in which heart tissue stiffens, as well as a host of other modern-day ailments that the monstrous snakes seem to miraculously resist.

“Pythons can go months or even a year in the wild without eating and then consume something greater than their own body mass, yet nothing bad happens to them,” said senior author Leslie Leinwand, professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology at CU Boulder and chief scientific officer of the BioFrontiers Institute. “We believe they possess mechanisms that protect their hearts from things that would be harmful to humans. This study goes a long way toward mapping out what those are.”

Leinwand first started studying pythons nearly two decades ago, and her lab remains one of the few in the world looking to the constricting, non-venomous reptiles for clues to improve human health.

As much as 20 feet long, depending on the species, pythons are typically found in resource-scarce regions of Africa, South Asia and Australia. They fast for extended periods but when they do have the opportunity to eat, they can swallow a deer whole.

“Most people who use animal models to study disease and health typically focus on rats and mice, but there is a lot to learn from animals like pythons that have evolved ways to survive in extreme environments,” said Leinwand.

There are two kinds of heart growth in humans, explains Leinwand: Healthy, like the kind that comes with chronic endurance exercise, and unhealthy, like the kind that comes with disease.

Pythons, much like elite athletes, excel at healthy heart growth.

Her previous work has shown that over the course of about a week to 10 days after a meal, python hearts get much bigger, their heart rate doubles, and their bloodstream turns milky white with circulating fats which, surprisingly, nourish rather than harm their heart tissue.

The new study set out to explore how this all happens.

Researchers fed pythons who had fasted for 28 days a meal of 25% of their body weight and compared them to snakes who had not been fed.

They discovered that as the well-fed snakes’ hearts grew, specialized bundles of cardiac muscle called myofibrils— that help the heart expand and contract— radically softened, and contracted with roughly 50% greater force. Meanwhile, those same snakes had “profound epigenetic differences,” differences in which genes were turned on or off, than the fasting snakes

More research is necessary to identify precisely which genes and metabolites are at play and what they do, but the study suggests that some may nudge the python heart to burn fat instead of sugar for fuel. Notably, diseased hearts struggle to do this.

Stiff or fibrotic tissue drives disease in other organs beside the heart, including lungs and livers, so there could be applications there, too.

“We found that the python heart is basically able to radically remodel itself, becoming much less stiff and much more energy efficient, in just 24 hours,” said Leinwand. “If we can map out how the python does this and harness it to use therapeutically in people it would be extraordinary.”

END

Study of pythons could lead to new therapies for heart disease, other illnesses

The snakes swiftly strengthen their heart and boost their metabolism to digest their massive meals; Scientists want to know their secret

2024-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study finds no link between migraine and Parkinson’s disease

2024-08-21

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL 4 P.M. ET, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 21, 2024

MINNEAPOLIS – Contrary to previous research, a new study of female participants finds no link between migraine and the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The study is published in the August 21, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“These results are reassuring for women who have migraine, which itself causes many burdens, that they don’t have to worry about an increased risk ...

How personality traits might interact to affect self-control

2024-08-21

Neuroticism may moderate the relationship between certain personality traits and self-control, and the interaction effects appear to differ by the type of self-control, according to a study published August 21, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Fredrik Nilsen from the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Defence University, Norway, and colleagues.

Self-control is important for mental and physical health, and certain personality traits are linked to the trait. Previous studies suggest that conscientiousness and extraversion enhance self-control, whereas neuroticism hampers it. However, the link between personality ...

US Congress members’ wealth statistically linked with ancestors’ slaveholding practices

2024-08-21

Per a new study, as of April 2021, US Congress members whose ancestors enslaved 16 or more people had a net worth that was five times higher than that of legislators whose ancestors did not have slaves. Neil Sehgal of the University of Pennsylvania, US, and Ashwini Sehgal of Case Western Reserve University, US present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on August 21, 2024.

Prior research has linked slavery’s intergenerational effects to contemporary inequality, poverty, education, voting behavior, and life expectancy in the US However, the extent to which past slavery in the US contributes to today’s social and economic conditions remains ...

Following a Mediterranean diet may be associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 infection, per systematic review

2024-08-21

Following a Mediterranean diet may be associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 infection, per systematic review, although it's unclear if the diet is also associated with reduced symptoms and severity of illness.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0301564

Article Title: Relevance of Mediterranean diet as a nutritional strategy in diminishing COVID-19 risk: A systematic review

Author Countries: Indonesia

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. END ...

Homicide rates are a major factor in the gap between Black and White life expectancy

2024-08-21

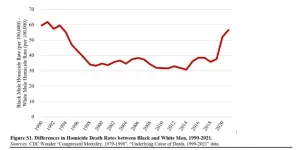

Homicide is a major reason behind lower and more variable reduction in life expectancy for Black rather than White men in recent years, according to a new study published August 21, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Michael Light and Karl Vachuska of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a staggering drop in U.S. life expectancy and substantially widened Black-White disparities in lifespan. It also coincided with the largest one-year increase in the U.S. homicide rate in more than a century, with Black men bearing the brunt of these. Despite these trends, there has been limited research on the contribution ...

Human-wildlife overlap expected to increase across more than half of land on Earth by 2070

2024-08-21

ANN ARBOR—As the human population grows, more than half of Earth's land will experience an increasing overlap between humans and animals by 2070, according to a University of Michigan study.

Greater human-wildlife overlap could lead to more conflict between people and animals, say the U-M researchers. But understanding where the overlap is likely to occur—and which animals are likely to interact with humans in specific areas—will be crucial information for urban planners, conservationists and countries that have pledged international conservation commitments. Their findings ...

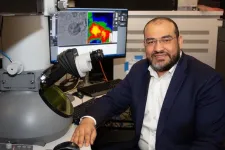

Freeze-frame: U of A researchers develop world's fastest microscope that can see electrons in motion

2024-08-21

Imagine owning a camera so powerful it can take freeze-frame photographs of a moving electron – an object traveling so fast it could circle the Earth many times in a matter of a second. Researchers at the University of Arizona have developed the world's fastest electron microscope that can do just that.

They believe their work will lead to groundbreaking advancements in physics, chemistry, bioengineering, materials sciences and more.

"When you get the latest version of a smartphone, it comes with a better camera," said Mohammed Hassan, associate professor of physics and optical sciences. "This transmission electron microscope is ...

Study finds highest prediction of sea-level rise unlikely

2024-08-21

In recent years, the news about Earth's climate—from raging wildfires and stronger hurricanes, to devastating floods and searing heat waves—has provided little good news.

A new Dartmouth-led study, however, reports that one of the very worst projections of how high the world's oceans might rise as the planet's polar ice sheets melt is highly unlikely—though it stresses that the accelerating loss of ice from Greenland and Antarctica is nonetheless dire.

The study challenges a new and alarming prediction in the latest high-profile report from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on ...

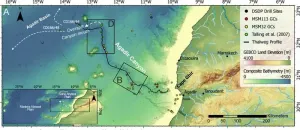

New study reveals devastating power and colossal extent of a giant underwater avalanche off the Moroccan coast

2024-08-21

New research by the University of Liverpool has revealed how an underwater avalanche grew more than 100 times in size causing a huge trail of destruction as it travelled 2000km across the Atlantic Ocean seafloor off the North West coast of Africa.

In a study publishing in the journal Science Advances (and featured on the front cover), researchers provide an unprecedented insight into the scale, force and impact of one of nature’s mysterious phenomena, underwater avalanches.

Dr Chris Stevenson, a sedimentologist from the University of Liverpool’s School of Environmental Sciences, co-led the team that for the first time has mapped a giant underwater avalanche from head ...

To kill mammoths in the Ice Age, people used planted pikes, not throwing spears, researchers say

2024-08-21

How did early humans use sharpened rocks to bring down megafauna 13,000 years ago? Did they throw spears tipped with carefully crafted, razor-sharp rocks called Clovis points? Did they surround and jab mammoths and mastadons? Or did they scavenge wounded animals, using Clovis points as a versatile tool to harvest meat and bones for food and supplies?

UC Berkeley archaeologists say the answer might be none of the above.

Instead, researchers say humans may have braced the butt of their pointed spears against the ground and angled the weapon upward in a way that would impale a charging animal. The force would have driven the spear deeper ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Study of pythons could lead to new therapies for heart disease, other illnessesThe snakes swiftly strengthen their heart and boost their metabolism to digest their massive meals; Scientists want to know their secret