(Press-News.org) How did the bodies of animals, including ours, become such fine-tuned movement machines? How vertebrates coordinate the eternal tug-o-war between involuntary reflexes and seamless voluntary movements is a mystery that Francisco Valero-Cuevas’ Lab in USC Alfred E. Mann Department of Biomedical Engineering, set out to understand. The Lab’s newest computational paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) adds to the thought leadership about the processing of sensory information and control of reflexes during voluntary movements—with implications as to how its disruption could give rise to motor disorders in neurological conditions like stroke, cerebral palsy, and Parkinson’s disease.

Do you remember the pediatrician tapping your knee to see if you had a strong involuntary knee-jerk reaction? This was to test the stretch reflexes in your spinal cord, which resist muscle stretching to give you muscle tone to hold your body up against gravity for example, fast corrections after tripping. So, how exactly those reflexes are modulated or inhibited to allow smooth, voluntary movement has been debated since Charles Scott Sherrington’s foundational work in the 1880s (yes, the 1880s!). This new work cuts directly into critical debates about how the ancient spinal cord and the relatively new human brain interact to produce smooth movements and how some neurological conditions disrupt this fine balance and produce slow, inaccurate, jerky, etc. movements in neurological conditions.

The study, led by Biomedical engineering doctoral student Grace Niyo, sheds light on a possible undiscovered system or circuitry at play within the spinal cord that, when working properly, “modulates” reflexes during voluntary movements. The study, Niyo says, proposes “a theoretically new mechanism to modulate spinal reflexes at the same spinal cord level as stretch reflexes.”

Valero-Cuevas, Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Computer Science, and Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy at USC, is the corresponding author of the paper "A computational study of how α- to γ-motoneurone collateral can mitigate velocity-dependent stretch reflexes during voluntary movement.

He says, “Reflexes are sophisticated and ancient low-level information exchange mechanisms that co-evolved and co-adapted with later developments like the human brain…understanding their collaboration with the brain is critical to understanding movement in health and disease.”

Valero-Cuevas says, "We are constantly benefiting from, and modulating stretch reflexes, whether we realize it or not as we stand, move and act."

Professor Valero-Cuevas’ lab is dedicated to understanding neuromuscular control in animals and robots, with implications for clinical rehabilitation for human mobility.

He explains, “Although our brain is highly sophisticated, we need to recognize the value and power of the ancient spinal cord—which has allowed all vertebrates to thrive for millions of years before large brains were even possible. We would like to understand how the spinal cord is able to regulate smooth movements, even with minimal brain control, as we know happens in amphibians and reptiles. This perspective could have important implications for understanding, and possibly treating, movement disorders in neurological conditions that affect the brain, spinal cord, or both—and also for creating biologically-inspired prostheses or robots that move smoothly using simulated spinal cords.”

The simulation experiment: To test whether and how a spinal circuit can allow voluntary movements by modulating or inhibiting movement perturbations that arise from stretch reflexes, the team, led by Niyo, created a biomechanical model of the arm of a macaque monkey in the physics simulator software called MuJoCo, generating over one thousand reaching movements. The simple stretch reflex rule is that muscles being stretched will tend to oppose the stretch, while muscles that are shortening do not show stretch reflexes. They first demonstrated that unmodulated stretch reflexes indeed produce a self-perturbation that disrupts voluntary arm movements. They then implemented a simple spinal circuit whereby the same neurons in the spinal cord that control muscle force (called alpha motoneurons) also scale (i.e., modulate) the stretch reflex proportionally to their level of muscle excitation. That is, highly excited muscles would have strong stretch reflex responses if stretched, and vice versa. They found that this simple rule—that it is physiologically possible given the known projections from alpha motoneurones (also called collaterals) to the reflex circuitry can—by itself—largely correct the self-perturbations from stretch reflexes to produce smooth and accurate voluntary movements.

From a modern engineering perspective, one might compare this to “edge computing,” says Valero-Cuevas, which is the idea that information processing is done at the source (limb sensors and the spinal cord) instead of exclusively at the central command center (the brain)—much like some apps in your phone that pre-processes information to be sent to a cloud server. Valero-Cuevas makes the mechanical analogy to these low-level connections to the reflex circuitry being like the “training wheels on a bicycle that are there to allow you to have fun, and catch you should you make a mistake while you learn to ride your bicycle.”

These circuits may help you produce novel voluntary movements with minimal perturbations but leave open the possibility of the brain and cerebellum to also refine and learn to control reflexes as your nervous system matures or gains enough experience.

Implications: Beyond better understanding movement disorders, Niyo says this knowledge could be a starting point for experimentalists to start looking for and testing for such spinal circuits. “This work could also inspire and guide new therapies at the appropriate level of the nervous system for treatment of movement disorders like stroke and cerebral palsy,” say Niyo and Valero-Cuevas.

The study's additional co-authors include Lama I. Almofeez, a PhD student in the USC Alfred E Man Department of Biomedical Engineering and Andrew Erwin, who at the time of the study was a Post-doctoral scholar in the USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy.

END

How are stretch reflexes modulated during voluntary movement?

New computational theory sheds light on a longstanding question

2024-09-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

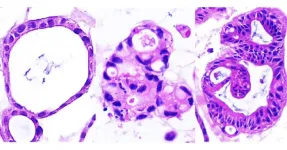

Organoids derived from gut stem cells reveal two distinct molecular subtypes of crohn’s disease

2024-09-26

Crohn’s disease — an autoimmune disorder — is characterized by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, resulting in a slew of debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms that vary from patient to patient. Complications of the disease can destroy the gut lining, requiring repeated surgeries. The poorly understood condition, which currently has no cure and few treatment options, often strikes young people, causing significant ill-health throughout their lifetime. One barrier to making progress in developing treatments has been the lack of preclinical animal models that accurately ...

Rates of sudden unexpected infant death changed during the COVID-19 pandemic

2024-09-26

HERSHEY, Pa. — The risk of sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period, especially in 2021, according to a new study led by researchers at the Penn State College of Medicine. Monthly increases in SUID in 2021 coincided with a resurgence of seasonal respiratory viruses, particularly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), suggesting that the shift in SUID rates may be associated with altered infectious disease transmission.

They ...

Genetic rescue for rare red foxes?

2024-09-26

A rescue effort can take many forms – a life raft, a firehose, an airlift. For animals whose populations are in decline from inbreeding, genetics itself can be a lifesaver.

Genomic research led by the University of California, Davis, reveals clues about montane red foxes’ distant past that may prove critical to their future survival. The study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, examines the potential for genetic rescue to help restore populations of these mountain-dwelling red foxes. The research is especially relevant for the estimated ...

Extreme heat impacts daily routines and travel patterns, study finds

2024-09-26

A groundbreaking new study conducted by a team of researchers from Arizona State University, University of Washington and the University of Texas at Austin reveals that extreme heat significantly alters how people go about their daily lives, influencing everything from time spent at home to transportation choices. The study, titled "Understanding How Extreme Heat Impacts Human Activity-Mobility and Time Use Patterns," was recently published in Transportation Research Part D and underscores the urgent need for policy action ...

ReadCube expands literature management with new AI Assistant and comprehensive search

2024-09-26

Digital Science announces ReadCube Pro, an AI-powered expansion of ReadCube, offering researchers new tools to simplify and accelerate literature management and literature monitoring workflows.

The new AI Assistant and Literature Monitoring in ReadCube – an award-winning leader in literature management and full-text document delivery – transform the way research teams access, organize, review and monitor scholarly literature by providing them with enhanced search capabilities while helping to significantly reduce time spent ...

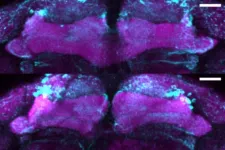

New mutation linked to early-onset Parkinsonism

2024-09-26

Leuven, 26 September 2024 – A team of scientists led by Prof. Patrik Verstreken (VIB-KU Leuven) has identified a new genetic mutation that may cause a form of early-onset Parkinsonism. The mutation, located in a gene called SGIP1, was discovered in an Arab family with a history of Parkinson's symptoms that began at a young age. The study reveals that this mutation affects how brain cells communicate, providing new insights into the disease's development and potential treatment strategies.

A genetic clue to Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a group of neurological disorders that share similar symptoms, including motor dysfunction ...

Bacteria involved in gum disease linked to increased risk of head and neck cancer

2024-09-26

More than a dozen bacterial species among the hundreds that live in people’s mouths have been linked to a collective 50% increased chance of developing head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), a new study shows. Some of these microbes had previously been shown to contribute to periodontal disease, serious gum infections that can eat away at the jawbone and the soft tissues that surround teeth.

Experts have long observed that those with poor oral health are statistically more vulnerable than those with healthier ...

These fish use legs to taste the seafloor

2024-09-26

Sea robins are unusual animals with the body of a fish, wings of a bird, and walking legs of a crab. Now, researchers show that the legs of the sea robin aren’t just used for walking. In fact, they are bona fide sensory organs used to find buried prey while digging. This work appears in two studies published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 26.

“This is a fish that grew legs using the same genes that contribute to the development of our limbs and then repurposed these legs to find ...

This fish has legs

2024-09-26

Sea robins are ocean fish particularly suited to their bottom-dwelling lifestyle: Six leg-like appendages make them so adept at scurrying, digging, and finding prey that other fish tend to hang out with them and pilfer their spoils.

A chance encounter in 2019 with these strange, legged fish at Cape Cod’s Marine Biological Laboratory was enough to inspire Corey Allard to want to study them.

“We saw they had some sea robins in a tank, and they showed them to us, because they know we like weird animals,” said Allard, a ...

Climate change: Heat, drought, and fire risk increasing in South America

2024-09-26

The number of days per year that are simultaneously extremely hot, dry, and have a high fire risk have as much as tripled since 1970 in some parts of South America. The results are published in a study in Communications Earth & Environment.

South America is warming at a similar rate to the global average. However, some regions of the subcontinent are more at risk of the co-occurrence of multiple climate extremes. These compound extremes can have amplified impacts on ecosystems, economy, and human health.

Raúl Cordero and colleagues calculated the number of days per year that each approximately 30 by 30 km grid ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

Could “cyborg” transplants replace pancreatic tissue damaged by diabetes?

Hearing a molecule’s solo performance

Justice after trauma? Race, red tape keep sexual assault victims from compensation

Columbia researchers awarded ARPA-H funding to speed diagnosis of lymphatic disorders

[Press-News.org] How are stretch reflexes modulated during voluntary movement?New computational theory sheds light on a longstanding question