(Press-News.org) Carbon capture, or the isolation and removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during industrial processes like cement mixing or steel production, is widely regarded as a key component of fighting climate change. Existing carbon capture technologies, such as amine scrubbing, are hard to deploy because they require significant energy to operate and involve corrosive compounds.

As a promising alternative, researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have developed carbon capture systems that use molecules called quinones, dissolved in water, as their capturing compounds. A new study in Nature Chemical Engineering provides critical insights into the mechanisms of carbon capture in these safer, gentler, water-based electrochemical systems, paving the way for their further refinement.

Led by former Harvard postdoctoral fellow Kiana Amini, now an assistant professor at University of British Columbia, the study outlines the detailed chemistry of how an aqueous, quinone-mediated carbon capture system works, showcasing the interplay of two types of electrochemistry that contribute to the system’s performance.

The study’s senior author is Michael J. Aziz, the Gene and Tracy Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies at SEAS. Aziz’ lab previously invented a redox flow battery technology that uses similar quinone chemistry to store energy for commercial and grid applications.

Quinones are abundant, small organic molecules found in both crude oil and rhubarb that can convert, trap, and release CO2 from the atmosphere many times over. Through lab experiments, the Harvard team knew that quinones trap carbon in two distinct ways. These two processes happen simultaneously, but the researchers have been unsure of each one’s contributions to overall carbon capture – as if their experimental electrochemical device were a black box.

This study opens the box.

“If we are serious about developing this system to be the best it can be, we need to know the mechanisms that are contributing to the capture, and the amounts … we had never measured the individual contributions of these mechanisms,” Amini said.

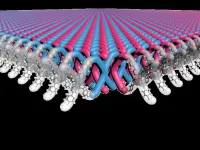

One of the ways dissolved quinones trap carbon is a form of direct capture, in which quinones receive an electrical charge and undergo a reduction reaction that gives them affinity to CO2. The process allows quinones to attach to the CO2 molecules, resulting in chemical complexes called quinone-CO2 adducts.

The other way is a form of indirect capture in which the quinones are charged and consume protons,which increases the solution’s pH. This allows CO2 to react with the now-alkaline medium to form bicarbonate or carbonate compounds.

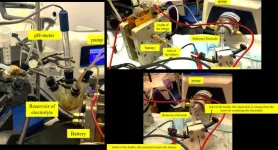

The researchers devised two real-time experimental methods for quantifying each mechanism. In the first, they used reference electrodes to measure voltage signature differences between the quinones and resulting quinone-CO2 adducts.

In the second, they used fluorescence microscopy to distinguish between oxidized, reduced, and adduct chemicals and quantified their concentrations at very fast time resolutions. This was possible because they discovered that the compounds involved in quinone-mediated carbon capture have unique fluorescence signatures.

“These methods allow us to measure contributions of each mechanism during operation,” Amini said. “By doing so, we can design systems that are tailored to specific mechanisms and chemical species.”

The research advances understanding of aqueous quinone-based carbon capture systems and provides tools for tailoring designs to different industrial applications. While challenges remain, such as oxygen sensitivity that can hinder performance, these findings open new avenues for investigation.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

END

The ins and outs of quinone carbon capture

Goal is safe, cost-effective greenhouse gas removal technologies

2025-01-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Laboratory for Laser Energetics at the University of Rochester launches IFE-STAR ecosystem and workforce development initiatives

2025-01-16

The University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE) has been awarded a $2.25 million grant over three years from the US Department of Energy’s Office of Fusion Energy Sciences. This funding establishes the Inertial Fusion Energy Science and Technology Accelerated Research (IFE-STAR) ecosystem that brings together academia, national laboratories, and the private sector to develop a clean, safe, and virtually limitless energy source, built on US leadership in inertial fusion.

Inertial ...

Most advanced artificial touch for brain-controlled bionic hand

2025-01-16

For the first time ever, a complex sense of touch for individuals living with spinal cord injuries is a step closer to reality. A new study published in Science, paves the way for complex touch sensation through brain stimulation, whilst using an extracorporeal bionic limb, that is attached to a chair or wheelchair.

The researchers, who are all part of the US-based Cortical Bionics Research Group, have discovered a unique method for encoding natural touch sensations of the hand via specific microstimulation patterns in implantable electrodes in the brain. This allows individuals with spinal cord injuries ...

Compounding drought and climate effects disrupt soil water dynamics in grasslands

2025-01-16

A novel field experiment in Austria reveals that compounding climate conditions – namely drought, warming, and elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2 ) – could fundamentally reshape how water moves through soils in temperate grasslands. The findings provide new insights into post-drought soil water flow, in particular. Soil water, though a minuscule fraction of Earth's total water resources, plays a critical role in sustaining terrestrial life on Earth by regulating biogeochemical cycles, surface energy balance, and plant productivity. Soils also govern ...

Multiyear “megadroughts” becoming longer and more severe under climate change

2025-01-16

Severe droughts are becoming hotter, longer, and increasingly devastating to ecosystems as climate change accelerates, according to a new study, which reports that temperate grasslands, including in parts of the United States, are facing the worst effects. The findings provide a global quantitative understanding of multiyear droughts (MYDs) – prolonged events lasting years or decades – and offer a benchmark for understanding their global trends and impacts. As droughts become more frequent ...

Australopithecines at South African cave site were not eating substantial amounts of meat

2025-01-16

Seven Australopithecus specimens uncovered at the Sterkfontein fossil site in South Africa were herbivorous hominins who did not eat substantial amounts of meat, according to a new study by Tina Lüdecke and colleagues. Lüdecke et al. analyzed organic nitrogen and carbonate carbon isotopes extracted from tooth enamel in the fossil specimens to determine the hominin diets. Some researchers have hypothesized that the incorporation of animal-based foods in early hominin diets led to increased brain size, smaller gut size ...

An AI model developed to design proteins simulates 500 million years of protein evolution in developing new fluorescent protein

2025-01-16

Guided by a multimodal generative language model called ESM3, Thomas Hayes and colleagues generated and synthesized a previously unknown bright fluorescent protein, with a genetic sequence so different from known fluorescent proteins that the researchers say its creation is equivalent to ESM3 simulating 500 million years of biological evolution. The model could provide a new way to “search” the space of protein possibilities with an eye to better understanding how naturally evolved proteins work, as well as developing novel proteins for uses in medicine, environmental remediation, and a host of other applications. ESM3 can reason over protein ...

Fine-tuned brain-computer interface makes prosthetic limbs feel more real

2025-01-16

You can probably complete an amazing number of tasks with your hands without looking at them. But if you put on gloves that muffle your sense of touch, many of those simple tasks become frustrating. Take away proprioception — your ability to sense your body’s relative position and movement — and you might even end up breaking an object or injuring yourself.

“Most people don’t realize how often they rely on touch instead of vision — typing, walking, picking up a flimsy cup of water,” said Charles Greenspon, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of Chicago. “If you can’t feel, you have ...

New chainmail-like material could be the future of armor

2025-01-16

EVANSTON, Il. --- In a remarkable feat of chemistry, a Northwestern University-led research team has developed the first two-dimensional (2D) mechanically interlocked material.

Resembling the interlocking links in chainmail, the nanoscale material exhibits exceptional flexibility and strength. With further work, it holds promise for use in high-performance, light-weight body armor and other uses that demand lightweight, flexible and tough materials.

Publishing on Friday (Jan. 17) in the journal ...

The megadroughts are upon us

2025-01-16

Increasingly common since 1980, persistent multi-year droughts will continue to advance with the warming climate, warns a study from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research (WSL), with Professor Francesca Pellicciotti from the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) participating. This publicly available forty-year global quantitative inventory, now published in Science, seeks to inform policy regarding the environmental impact of human-induced climate change. It also detected previously ‘overlooked’ events.

Fifteen years of a persistent, devastating megadrought—the longest lasting in a thousand years—have nearly dried out ...

Eavesdropping on organs: Immune system controls blood sugar levels

2025-01-16

When we think about the immune system, we usually associate it with fighting infections. However, a study published in Science by the Champalimaud Foundation reveals a surprising new role. During periods of low energy—such as intermittent fasting or exercise—immune cells step in to regulate blood sugar levels, acting as the “postman” in a previously unknown three-way conversation between the nervous, immune and hormonal systems. These findings open up new approaches for managing conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cancer.

Rethinking the Immune ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

AI-driven chart review accurately identifies potential rare disease trial participants in new study

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

Strong alcohol policy could reduce cancer in Canada

Air pollution from wildfires linked to higher rate of stroke

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

[Press-News.org] The ins and outs of quinone carbon captureGoal is safe, cost-effective greenhouse gas removal technologies