(Press-News.org) EVANSTON, Ill. --- You’ve probably heard the phrase, “It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it,” and now, science backs it up. A first-of-its-kind study from Northwestern University’s School of Communication, the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Wisconsin-Madison reveals a region of the brain, long known for early auditory processing, plays a far greater role in interpreting speech than previously understood.

The multidisciplinary study being published Monday, March 3 in the journal Nature Communications found a brain region known as Heschl’s gyrus doesn’t just process sounds — it transforms subtle changes in pitch, known as prosody, into meaningful linguistic information that guides how humans understand emphasis, intent and focus in conversation.

For years, scientists believed that all aspects of prosody were primarily processed in the superior temporal gyrus, a brain region known for speech perception. Bharath Chandrasekaran, the study’s co-principal investigator and professor and chair of the Roxelyn and Richard Pepper Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at Northwestern, said the findings challenge long-held assumptions about how, where and the speed at which prosody is processed in the brain.

“The results redefine our understanding of the architecture of speech perception,” Chandrasekaran said. “We’ve spent a few decades researching the nuances of how speech is abstracted in the brain, but this is the first study to investigate how subtle variations in pitch that also communicate meaning is processed in the brain.”

Rare set of research participants

Chandrasekaran partnered with Dr. Taylor Abel, chief of pediatric neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine to study auditory information processing in 11 adolescent patients who were receiving neurosurgery treatment for severe epilepsy. They all had electrodes implanted deep in the cortex of the brain that is critical for key language function.

“Typically, communication and linguistics research rely on non-invasive recordings from the surface of the skin, which makes it accessible but not very precise,” Abel said. “A collaboration between neurosurgeon-scientists and neuroscientists, like ours, allowed us to collect high-quality recordings of brain activity that would not have been possible otherwise, and learn about the mechanisms of brain processing in a completely new way.”

To explore how the brain deciphers the melody of speech, researchers worked with the rare group of patients who had electrodes implanted in their brains as part of epilepsy treatment. While these patients actively listened to an audiobook recording of “Alice in Wonderland,” scientists tracked activity in multiple brain regions in real time.

What researchers found

Using the intracerebral recordings from the electrodes deep in the patient’s brain, researchers noted the Heschl’s gyrus section processed subtle changes in voice pitch — not just as sound, but as meaningful linguistic units. The brain encoded pitch accents separately from the sounds that make up words.

“Our study challenges the long-standing assumptions how and where the brain picks up on the natural melody in speech — those subtle pitch changes that help convey meaning and intent,” said G. Nike Gnanataja of UW-Madison’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders and co-first author of the study. “Even though these pitch patterns vary each time we speak, our brains create stable representations to understand them.”

Gnanataja says the research also revealed that the hidden layer of meaning carried by prosodic contours — the rise and fall of speech — is encoded much earlier in auditory processing than previously thought.

Similar research was conducted in non-human primates, but researchers found those brains lacked this abstraction, despite processing the same acoustic cues.

Why it matters

By unlocking the hidden layer of speech, Chandrasekaran and his team discovered how the brain processes pitch accents, revealing profound implications for various fields.

“Our findings could transform speech rehabilitation, AI-powered voice assistants, and our understanding of what makes human communication unique,” he said.

Understanding early prosodic processing could lead to new interventions for speech and language disorders, such as autism, dysprosody in patients who have had a stroke, and language-based learning differences.

The study also highlights the unique role of linguistic experience in human communication, as non-human primates lack the ability to process pitch accents as abstract categories.

Additionally, these findings could significantly enhance AI-driven voice recognition systems by enabling them to better handle prosody, bringing natural language processing closer to mimicking human speech perception.

The study is titled “Cortical processing of discrete prosodic patterns in continuous speech.” The research is supported by NIH grant 5R01DC13315-11 awarded by the National Institute of Health and is a product of an ongoing research project titled “Cortical contributions to frequency-following response generation and modulation,” co-principal investigators Bharath Chandrasekaran, Taylor Abel, Srivatsun Sadagopan, Tobias Teichert. The research was also supported by NIH grant R21DC019217-01A1 awarded to Taylor Abel; and the Vice-Chancellors Research and Graduate Education, and College of Letters and Sciences UW Madison Funds to G. Nike Gnanateja.

END

It’s not just what you say – it’s also how you say it

New Northwestern study reveals how the brain decodes changes in the pitch of our speech to shape meaning

2025-03-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sleep patterns may reveal comatose patients with hidden consciousness

2025-03-03

NEW YORK, NY (March 3, 2025)--Several studies in the past decade have revealed that up to a quarter of unresponsive patients with recent brain injuries may possess a degree of consciousness that’s normally hidden from their families and physicians.

New research from Columbia University and NewYork-Presbyterian may soon help physicians identify unresponsive brain-injury patients with hidden consciousness who are likely to achieve long-term recovery by looking for brain waves that are indicative of normal sleep patterns.

“We’re at an exciting crossroad in neurocritical care where we know that many patients appear to be unconscious, but some are recovering without ...

3D genome structure guides sperm development

2025-03-03

Two new landmark studies show how a seeming tangle of DNA is actually organized into a structure that coordinates thousands of genes to form a sperm cell. The work, published March 3 as two papers in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, could improve treatment for fertility problems and developmental disorders.

“We are finding the 3D structure of the genome,” said Satoshi Namekawa, professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of California, Davis and senior author on one of the papers. “This is really showing us how the genomic architecture guides development.”

Although DNA is a long, stringy molecule, in living ...

Certain genetic alterations may contribute to the primary resistance of colorectal and pancreatic cancers to KRAS G12C inhibitors

2025-03-03

Bottom Line: Colorectal cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma that harbored the KRAS G12C mutation often carried other genetic alterations that can be associated with resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors, despite no prior treatment with this therapy, according to recent results from a large multidatabase analysis.

Journal in Which the Study was Published: Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR)

Author: Hao Xie, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

Background: “The KRAS pathway plays a crucial role in cell biology by regulating ...

Melting Antarctic ice sheets will slow Earth’s strongest ocean current

2025-03-03

Melting ice sheets are slowing the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), the world’s strongest ocean current, researchers have found.

This melting has implications for global climate indicators, including sea level rise, ocean warming and viability of marine ecosystems.

The researchers, from the University of Melbourne and NORCE Norway Research Centre, have shown the current slowing by around 20 per cent by 2050 in a high carbon emissions scenario.

This influx of fresh water into the Southern Ocean is expected to change ...

Hallucinogen use linked to 2.6-fold increase in risk of death for people needing emergency care

2025-03-03

People seeking emergency care for hallucinogen use were at 2.6-fold higher risk of death within 5 years than the general population, according to a new study published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.241191.

The use of hallucinogens, such as ketamine, psychedelics, psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, and MDMA (Ecstasy), has rapidly increased since the mid-2010s, especially in Canada and the United States. In the US, the percentage of people reporting they used hallucinogens more than doubled from 3.8% in 2016 to 8.9% in 2021. “In Canada, an estimated 5.9% of people used a psychedelic ...

Pathogenicity threshold of SCA6 causative gene CACNA1A was identified

2025-03-03

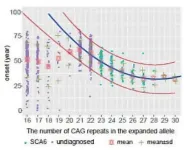

Niigata, Japan - The Department of Neurology at Niigata University and National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry(NCNP) has identified pathogenic thresholds for the CAG repeat units (RU) of the CACNA1A gene that causes SCA6. They investigated the SCA6 causative gene in 2,768 patients. They carefully examined the relationship between RU, age of onset, and family history. First, in cases with 18 or fewer RU, the proportion of family history was low. For 19 or more RU, the proportion of family history ...

Mysterious interstellar icy objects

2025-03-03

Niigata, Japan - Organic molecules that serve as the building blocks of life are believed to form in space, but their exact formation sites and delivery mechanisms to planets remain a major mystery in astronomy and planetary science. One of the key elements in solving this mystery is the presence of ice in interstellar environments. In cold, dense, and shielded regions of the galaxy, atoms and molecules adhere to the surfaces of submicron-sized solid particles (dust), leading to the formation of interstellar ices. This process is similar to how snow forms in Earth’s clouds.

Astronomers from Niigata University and ...

Chronic diseases misdiagnosed as psychosomatic can lead to long term damage to physical and mental wellbeing, study finds

2025-03-03

A ‘chasm of misunderstanding and miscommunication’ is often experienced between clinicians and patients, leading to autoimmune diseases such as lupus and vasculitis being wrongly diagnosed as psychiatric or psychosomatic conditions, with a profound and lasting impact on patients, researchers have found.

A study involving over 3,000 participants – both patients and clinicians – found that these misdiagnoses (sometimes termed “in your head” by patients) were often associated with long term impacts on patients’ physical health and wellbeing and damaged trust in healthcare services.

The researchers are calling for greater awareness ...

Omalizumab treats multi-food allergy better than oral immunotherapy

2025-03-02

A clinical trial has found that the medication omalizumab, marketed as Xolair, treated multi-food allergy more effectively than oral immunotherapy (OIT) in people with allergic reactions to very small amounts of common food allergens. OIT, the most common approach to treating food allergy in the United States, involves eating gradually increasing doses of a food allergen to reduce the allergic response to it. Thirty-six percent of study participants who received an extended course of omalizumab could tolerate 2 grams or more of peanut protein, or about eight peanuts, and two other ...

Sleep apnea linked to increased risk of Parkinson’s, but CPAP may reduce risk

2025-03-02

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL 4 P.M. ET, SUNDAY, MARCH 2, 2025

Media Contacts:

Renee Tessman, rtessman@aan.com, (612) 928-6137

Natalie Conrad, nconrad@aan.com, (612) 928-6164

Sleep apnea linked to increased risk of Parkinson’s, but CPAP may reduce risk

Risk reduced if treatment started within two years of diagnosis

MINNEAPOLIS – People with obstructive sleep apnea have an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, but if started early enough, continuous positive airway pressure ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] It’s not just what you say – it’s also how you say itNew Northwestern study reveals how the brain decodes changes in the pitch of our speech to shape meaning