(Press-News.org)

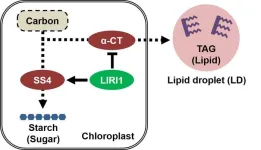

Plants store carbon in two primary forms: starch and triacylglycerols (TAGs). Starch is mainly stored in chloroplasts in leaves, where it serves as a readily available energy source, while TAGs are stored in seeds for long-term energy storage. Past studies have shown that a carbon trade-off exists between these two storage forms, implying that an increase in the levels of one form often reduces the levels of the other. Interestingly, attempts to increase TAG in leaves have led to a decrease in the levels of starch, suggesting that plants regulate carbon sources, prioritizing either starch or TAGs. Understanding this trade-off could lead to the development of plants with more TAG in their leaves, providing a sustainable source of plant oils.

Now, in a study published in the Journal of Experimental Botany on February 8, 2025, researchers from Chiba University, Japan, provide new insights into the factors controlling this carbon trade-off. Their findings reveal that a previously unreported gene –named LIRI1 –which encodes an unknown protein, plays a crucial role in regulating the balance between starch and lipid storage in plant leaves by influencing both fatty acid and starch biosynthesis pathways.

Led by Associate Professor Takashi L. Shimada, with Ms. Mebae Yamaguchi as the study’s first author, from the Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University, the research team used a forward genetics approach to identify the genes responsible for altered carbon storage patterns. They screened mutant Arabidopsis plants that exhibited higher leaf TAG levels and lower starch content, eventually identifying LIRI1 as a key regulator.

Talking about the rationale behind this study, Associate Professor Shimada says, "We were interested in how plants allocate carbon resources. Particularly, why do seeds accumulate so many lipids while leaves contain very little? Answering this question through our research has helped us contribute to both basic and applied science."

Instead of directly measuring the TAG content in leaves, which would be time-consuming, the researchers counted the number of lipid droplets (LDs) that store TAG in the leaves. To develop the mutants, the researchers treated Arabidopsis seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate, a chemical mutagen that induces random DNA mutations. The seeds carried a transgene encoding green fluorescent protein fused to CALEOSIN3, a protein that naturally localizes to LDs. This fluorescent tagging allowed the researchers to visualize LDs in the leaves of the seedlings under a fluorescence microscope. Among the screened plants, they discovered a mutant named lipid-rich 1-1 (liri1-1), which had five times more TAGs and half the starch content of wild-type plants.

The overaccumulation of LDs in liri1 mutants was found to be due to the loss of function of the LIRI1 gene in chloroplasts. The gene interacts with two key enzymes: ACETYL-COENZYME A CARBOXYLASE CARBOXYLTRANSFERASE ALPHA SUBUNIT (α-CT), which is essential for fatty acid biosynthesis, and STARCH SYNTHASE 4 (SS4), which is involved in starch biosynthesis.

Based on the observations, the researchers propose that in wild-type plants, LIRI1 promotes carbon allocation by activating starch production, inhibiting starch degradation, or encouraging carbon allocation to starch at the expense of TAG. However, when LIRI1 is defective, these mechanisms are disrupted, shifting carbon allocation toward TAG production instead of starch. The mutant liri1 plants were found to have growth defects and irregular chloroplasts, suggesting that proper carbon allocation between TAGs and starch plays a role in normal plant development.

These findings highlight the role of LIRI1 as a key regulator of starch-lipid balance in plants. Even as the demand for plant oil as a biofuel and food source increases worldwide, modifying LIRI1 could enable the development of crops with higher TAG storage in leaves, providing a renewable source for fulfilling this demand.

"The liri1 mutation could be useful for developing novel high-TAG crops or low-starch crops," says Associate Professor Shimada, while commenting on the real-life implications of these findings. Adding further, he says, "Such crops could eventually be tailored for human health, for example, as low-starch food options for people with diabetes."

About Associate Professor Takashi L. Shimada

Dr. Takashi L. Shimada is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Horticulture, Plant Molecular Science Center, and Research Center for Space Agriculture and Horticulture at Chiba University, Japan. Dr. Shimada investigates the intracellular structure of plants, especially lipid droplets. His research aims to comprehensively understand lipid storage in plants and enhance plant lipid production for potential application as a food resource. He has co-authored more than 20 reputed publications and is a member of multiple academic societies, including the Japanese Association of Plant Lipid Researchers and The Phytopathological Society of Japan.

END

An international team led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has discovered the most distant spiral galaxy candidate known to date. This ultra-massive system existed just one billion years after the Big Bang and already shows a remarkably mature structure, with a central old bulge, a large star-forming disk, and well-defined spiral arms. The discovery was made using data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and offers important insights into how galaxies can form and evolve so rapidly in the early Universe. The ...

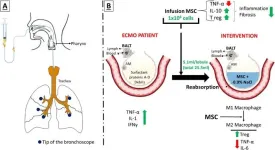

A multidisciplinary clinical team led by Professor Bernat Soria from the Institute of Bioengineering at the Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH, Spain) has developed a new method to deliver cell therapies in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a life support system used in cases of severe lung failure. The advance has been published in Stem Cell Research & Therapy (Springer Nature Group). The team has opted not to patent the technique in order to encourage its use in public health systems ...

A new study from University of California San Diego suggests that climate trauma — such as experiencing a devastating wildfire — can have lasting effects on cognitive function. The research, which focused on survivors of the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California, found that individuals directly exposed to the disaster had difficulty making decisions that prioritize long-term benefits. The findings were recently published in Scientific Reports, part of the Nature portfolio of journals.

“Our previous research has shown that survivors of California’s 2018 Camp Fire experience prolonged symptoms ...

Kyoto, Japan -- There's a sensation that you experience -- near a plane taking off or a speaker bank at a concert -- from a sound so total that you feel it in your very being. When this happens, not only do your brain and ears perceive it, but your cells may also.

Technically speaking, sound is a simple phenomenon, consisting of compressional mechanical waves transmitted through substances, which exists universally in the non-equilibrated material world. Sound is also a vital source of environmental information for living beings, while its capacity to induce physiological responses at the cell ...

Strawberry fields forever will exist for the in-demand fruit, but the laborers who do the backbreaking work of harvesting them might continue to dwindle. While raised, high-bed cultivation somewhat eases the manual labor, the need for robots to help harvest strawberries, tomatoes, and other such produce is apparent.

As a first step, Osaka Metropolitan University Assistant Professor Takuya Fujinaga has developed an algorithm for robots to autonomously drive in two modes: moving to a pre-designated destination and moving alongside ...

By Dr Kelly Dunning

The Endangered Species Act (ESA), now 50 years old, was once a rare beacon of bipartisan unity, signed into law by President Richard Nixon with near-unanimous political support. Its purpose was clear: protect imperiled species and enable their recovery using the best available science to do so. Yet, as our case study on the grizzly bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem reveals, wildlife management under the ESA has changed, becoming a political battleground where science is increasingly drowned out by partisan ideology, bureaucratic delays, power struggles, and competing political interests. ...

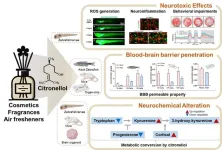

Citronellol, a rose-scented compound commonly found in cosmetics and household products, has long been considered safe. However, a Korean research team has, for the first time, identified its potential to cause neurotoxicity when excessively exposed.

A collaborative research team led by Dr. Myung Ae Bae at the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT) and Professors Hae-Chul Park and Suhyun Kim at Korea University has discovered that high concentrations of citronellol can trigger neurological and behavioral toxicity. The study, published in the Journal ...

Most people think of crocodylians as living fossils— stubbornly unchanged, prehistoric relics that have ruled the world’s swampiest corners for millions of years. But their evolutionary history tells a different story, according to new research led by the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) and the University of Utah.

Crocodylians are surviving members of a 230-million-year lineage called crocodylomorphs, a group that includes living crocodylians (i.e. crocodiles, alligators and gharials) and their many extinct ...

Images available via link in the notes section

University of Oxford researchers have helped overturn the popular theory that water on Earth originated from asteroids bombarding its surface;

Scientists have analysed a meteorite analogous to the early Earth to understand the origin of hydrogen on our planet.

The research team demonstrated that the material which built our planet was far richer in hydrogen than previously thought.

The findings, which support the theory that the formation of habitable conditions on Earth did not rely on asteroids ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A spat between birds at your backyard birdfeeder highlights the sometimes fierce competition for resources that animals face in the natural world, but some ecologically similar species appear to coexist peacefully. A classic study in songbirds by Robert MacArthur, one of the founders of modern ecology, suggested that similar wood warblers — insect-eating, colorful forest songbirds — can live in the same trees because they actually occupy slightly different locations in the tree and presumably eat different insects. Now, a new study is using modern techniques to revisit MacArthur’s ...