(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– Siberia's Lake Baikal, the world's oldest, deepest, and largest freshwater lake, has provided scientists with insight into the ways that climate change affects water temperature, which in turn affects life in the lake. The study is published in the journal PLoS ONE today.

"Lake Baikal has the greatest biodiversity of any lake in the world," explained co-author Stephanie Hampton, deputy director of UC Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis (NCEAS). "And, thanks to the dedication of three generations of a family of Russian scientists, we have remarkable data on climate and lake temperature."

Beginning in the 1940's, Russian scientist Mikhail Kozhov took frequent and detailed measurements of the lake's temperature. His descendants continued the practice, including his granddaughter, Lyubov Izmest'eva at Irkutsk State University. She is a co-author of the study and a core member of the NCEAS team now exploring this treasure trove of scientific and historical records.

First author Steve Katz, of NOAA's Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, explained that the research team discovered many climate variability signals, called teleconnections, in the data. For example, changes in Lake Baikal water temperature correlate with monthly variability in El Niño indices, reflecting sea surface temperatures over the Pacific Ocean tens of thousands of kilometers away. At the same time, Lake Baikal's temperatures are influenced by strong interactions with Pacific Ocean pressure fields described by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation.

"Teasing these multiple signals apart in this study illuminated both the methods by which we can detect these overlapping sources of climate variability, and the role of jet stream variability in affecting the local ecosystem," said Katz.

Hampton added: "This work is important because we need to go beyond detecting past climate variation. We also need to know how those climate variations are actually translated into local ecosystem fluctuations and longer-term local changes. Seeing how physical drivers of local ecology –– like water temperature –– are in turn reflecting global climate systems will allow us to determine what important short-term ecological changes may take place, such as changes in lake productivity. They also help us to forecast consequences of climate variability."

The scientists found that seasonality of Lake Baikal's surface water temperatures relate to the fluctuating intensity and path of the jet stream on multiple time scales. Although the lake has warmed over the past century, the changing of seasons was not found to trend in a single direction, such as later winters.

The climate indices reflect alterations in jet stream strength and trajectory, and these dynamics collectively appear to forecast seasonal onset in Siberia about three months in advance, according to the study. Lake Baikal's seasonality also tracked decadal-scale variations in the Earth's rotational velocity. The speed of the Earth's rotation determines the length of a day, which differs by milliseconds from day to day depending on the strength of atmospheric winds, including the jet stream. This scale of variability was also seen to affect the timing variability in seasonal lake warming and cooling, reinforcing the mechanistic role of the jet stream.

"Remarkably, the temperature record that reflects all these climate messages was collected by three generations of a single family of Siberian scientists, from 1946 to the present, and the correlation of temperature with atmospheric dynamics is further confirmation that this data set is of exceptionally high quality," said Katz. "This consistent dedication to understanding one of the world's most majestic lakes helps us understand not only the dynamics of Lake Baikal over the past 60 years, but also to recognize future scenarios for Lake Baikal. The statistical approach may be used for similar questions in other ecosystems, although we recognize that the exceptional quality and length of the Baikal data was one of the keys to our success."

INFORMATION:

Marianne V. Moore, of Wellesley College, is a leader of the NCEAS team and a co-author of this paper.

World's largest lake sheds light on ecosystem responses to climate variability

2011-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Model minority' not perceived as model leader

2011-02-18

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Asian Americans are widely viewed as "model minorities" on the basis of education, income and competence. But they are perceived as less ideal than Caucasian Americans when it comes to attaining leadership roles in U.S. businesses and board rooms, according to researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

In a groundbreaking study, researchers found that "race trumps other salient characteristics, such as one's occupation, regarding perceptions of who is a good leader," said Thomas Sy, assistant professor of psychology at UC Riverside and ...

Warm weather may hurt thinking skills in people with MS

2011-02-18

ST. PAUL, Minn. – People with multiple sclerosis (MS) may find it harder to learn, remember or process information on warmer days of the year, according to new research released today that will be presented at the American Academy of Neurology's 63rd Annual Meeting in Honolulu April 9 to April 16, 2011.

"Studies have linked warmer weather to increased disease activity and lesions in people with MS, but this is the first research to show a possible link between warm weather and cognition, or thinking skills, in people with the disease," said study author Victoria Leavitt, ...

Research predicts future evolution of flu viruses

2011-02-18

New research from the University of Pennsylvania is beginning to crack the code of which strain of flu will be prevalent in a given year, with major implications for global public health preparedness. The findings will be published on February 17 in the open-access journal PLoS Genetics.

Joshua Plotkin and Sergey Kryazhimskiy, both at the University of Pennsylvania, conducted the research with colleagues at McMaster University and the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Plotkin believes that his group's computational ...

The brain as a 'task machine'

2011-02-18

The portion of the brain responsible for visual reading doesn't require vision at all, according to a new study published online on February 17 in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication. Brain imaging studies of blind people as they read words in Braille show activity in precisely the same part of the brain that lights up when sighted readers read. The findings challenge the textbook notion that the brain is divided up into regions that are specialized for processing information coming in via one sense or another, the researchers say.

"The brain is not a sensory machine, ...

Eggs' quality control mechanism explained

2011-02-18

To protect the health of future generations, body keeps a careful watch on its precious and limited supply of eggs. That's done through a key quality control process in oocytes (the immature eggs), which ensures elimination of damaged cells before they reach maturity. In a new report in the February 18th Cell, a Cell Press publication, researchers have made progress in unraveling how a factor called p63 initiates the deathblow.

In fact, p63 is a close relative of the infamous tumor suppressor p53, and both proteins recognize DNA damage. Because of this heritage it ...

Male fertility is in the bones

2011-02-18

Researchers have found an altogether unexpected connection between a hormone produced in bone and male fertility. The study in the February 18th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication, shows that the skeletal hormone known as osteocalcin boosts testosterone production to support the survival of the germ cells that go on to become mature sperm.

The findings in mice provide the first evidence that the skeleton controls reproduction through the production of hormones, according to Gerard Karsenty of Columbia University and his colleagues.

Bone was once thought of as a ...

Bears uncouple temperature and metabolism for hibernation, new study shows

2011-02-18

This release is available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and Chinese on EurekAlert! Chinese.

Several American black bears, captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after wandering a bit too close to human communities, have given researchers the opportunity to study hibernation in these large mammals like never before. Surprisingly, the new findings show that although black bears only reduce their body temperatures slightly during hibernation, their metabolic activity drops dramatically, slowing to about 25 percent of their normal, active rates.

This ...

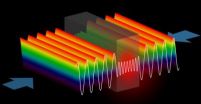

Scientists build world's first anti-laser

2011-02-18

New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light ...

The real avatar

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

Taking brain-computer interfaces to the next phase

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...