(Press-News.org) New research from the University of Pennsylvania is beginning to crack the code of which strain of flu will be prevalent in a given year, with major implications for global public health preparedness. The findings will be published on February 17 in the open-access journal PLoS Genetics.

Joshua Plotkin and Sergey Kryazhimskiy, both at the University of Pennsylvania, conducted the research with colleagues at McMaster University and the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Plotkin believes that his group's computational study of 40 years of flu genomes offers a new way of looking at mutations: by cataloging pairs of genetic changes that have occurred in rapid succession, observing that a mutation in one half of the pair can act as an early warning sign of a mutation about to occur in the other.

Tracking single mutations in a vacuum is not always enough to understand how the flu virus evolves. "Sometimes a mutation is functional or adaptive only if it's in the context of a certain genetic background – that is, if the protein already has some other mutation," Plotkin said. The influence such combinations have on an organization's adaptive fitness is known as epistasis.

"If you see a mutation occur in Site A and then very soon after you see a mutation in Site B, and this pattern happens repeatedly, then you have some evidence that A and B influence fitness epistatically," Plotkin said. "The first mutation might be useless on its own, but it might be a prerequisite for the second mutation to be useful. The first mutation is like giving you a nail, and the second one is like giving you a hammer."

Because the studied mutations generally affect the surface proteins that determine whether the virus can enter and infect human cells, being able to predict what mutations are likely to happen in the near future has lifesaving applications. Tens of thousands of Americans, and hundreds of thousands worldwide, die of seasonal flu complications every year. Flu vaccine production is labor intensive and time consuming; to have enough supplies ready for the flu season, public health groups like the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization must make an educated guess as to which strain is likely to be the most active several months in advance. Observing the leading site of an epistatic pair could give them a head start.

###

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Joshua B. Plotkin acknowledges funding from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the James S. McDonnell Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (HR0011-09-1-0055), and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (2U54AI057168). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

CITATION: Kryazhimskiy S, Dushoff J, Bazykin GA, Plotkin JB (2011) Prevalence of Epistasis in the Evolution of Influenza A Surface Proteins. PLoS Genet 7(2): e1001301. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001301

PLEASE ADD THIS LINK TO THE FREELY AVAILABLE ARTICLE IN ONLINE VERSIONS OF YOUR REPORT (the link will go live when the embargo ends): http://www.plosgenetics.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001301

Disclaimer

This press release refers to an upcoming article in PLoS Genetics. The release is provided by journal staff, or by the article authors and/or their institutions. Any opinions expressed in this release or article are the personal views of the journal staff and/or article contributors, and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of PLoS. PLoS expressly disclaims any and all warranties and liability in connection with the information found in the releases and articles and your use of such information.

About PLoS Genetics

PLoS Genetics (http://www.plosgenetics.org) reflects the full breadth and interdisciplinary nature of genetics and genomics research by publishing outstanding original contributions in all areas of biology. All works published in PLoS Genetics are open access. Everything is immediately and freely available online throughout the world subject only to the condition that the original authorship and source are properly attributed. Copyright is retained by the authors. The Public Library of Science uses the Creative Commons Attribution License.

About the Public Library of Science

The Public Library of Science (PLoS) is a non-profit organization of scientists and physicians committed to making the world's scientific and medical literature a freely available public resource. For more information, visit http://www.plos.org.

Research predicts future evolution of flu viruses

2011-02-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The brain as a 'task machine'

2011-02-18

The portion of the brain responsible for visual reading doesn't require vision at all, according to a new study published online on February 17 in Current Biology, a Cell Press publication. Brain imaging studies of blind people as they read words in Braille show activity in precisely the same part of the brain that lights up when sighted readers read. The findings challenge the textbook notion that the brain is divided up into regions that are specialized for processing information coming in via one sense or another, the researchers say.

"The brain is not a sensory machine, ...

Eggs' quality control mechanism explained

2011-02-18

To protect the health of future generations, body keeps a careful watch on its precious and limited supply of eggs. That's done through a key quality control process in oocytes (the immature eggs), which ensures elimination of damaged cells before they reach maturity. In a new report in the February 18th Cell, a Cell Press publication, researchers have made progress in unraveling how a factor called p63 initiates the deathblow.

In fact, p63 is a close relative of the infamous tumor suppressor p53, and both proteins recognize DNA damage. Because of this heritage it ...

Male fertility is in the bones

2011-02-18

Researchers have found an altogether unexpected connection between a hormone produced in bone and male fertility. The study in the February 18th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication, shows that the skeletal hormone known as osteocalcin boosts testosterone production to support the survival of the germ cells that go on to become mature sperm.

The findings in mice provide the first evidence that the skeleton controls reproduction through the production of hormones, according to Gerard Karsenty of Columbia University and his colleagues.

Bone was once thought of as a ...

Bears uncouple temperature and metabolism for hibernation, new study shows

2011-02-18

This release is available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese and Chinese on EurekAlert! Chinese.

Several American black bears, captured by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after wandering a bit too close to human communities, have given researchers the opportunity to study hibernation in these large mammals like never before. Surprisingly, the new findings show that although black bears only reduce their body temperatures slightly during hibernation, their metabolic activity drops dramatically, slowing to about 25 percent of their normal, active rates.

This ...

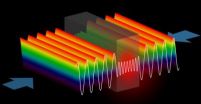

Scientists build world's first anti-laser

2011-02-18

New Haven, Conn.—More than 50 years after the invention of the laser, scientists at Yale University have built the world's first anti-laser, in which incoming beams of light interfere with one another in such a way as to perfectly cancel each other out. The discovery could pave the way for a number of novel technologies with applications in everything from optical computing to radiology.

Conventional lasers, which were first invented in 1960, use a so-called "gain medium," usually a semiconductor like gallium arsenide, to produce a focused beam of coherent light—light ...

The real avatar

2011-02-18

That feeling of being in, and owning, your own body is a fundamental human experience. But where does it originate and how does it come to be? Now, Professor Olaf Blanke, a neurologist with the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL and the Department of Neurology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, announces an important step in decoding the phenomenon. By combining techniques from cognitive science with those of Virtual Reality (VR) and brain imaging, he and his team are narrowing in on the first experimental, data-driven approach to understanding self-consciousness.

In ...

Taking brain-computer interfaces to the next phase

2011-02-18

You may have heard of virtual keyboards controlled by thought, brain-powered wheelchairs, and neuro-prosthetic limbs. But powering these machines can be downright tiring, a fact that prevents the technology from being of much use to people with disabilities, among others. Professor José del R. Millán and his team at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland have a solution: engineer the system so that it learns about its user, allows for periods of rest, and even multitasking.

In a typical brain-computer interface (BCI) set-up, users can send ...

Skeleton regulates male fertility

2011-02-18

NEW YORK (February 17, 2011) – Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center have discovered that the skeleton acts as a regulator of fertility in male mice through a hormone released by bone, known as osteocalcin.

The research, led by Gerard Karsenty, M.D., Ph.D., chair of the Department of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, is slated to appear online on February 17 in Cell, ahead of the journal's print edition, scheduled for March 4.

Until now, interactions between bone and the reproductive system have focused only on the influence ...

Put major government policy options through a science test first, biodiversity experts urge

2011-02-18

Scientific advice on the consequences of specific policy options confronting government decision makers is key to managing global biodiversity change.

That's the view of leading scientists anxiously anticipating the first meeting of a new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-like mechanism for biodiversity at which its workings and work program will be defined.

Writing in the journal Science, the scientists say the new mechanism, called the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), should adopt a modified working approach ...

Subtle shifts, not major sweeps, drove human evolution

2011-02-18

The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds.

Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species.

By examining the sequences of nearly ...