Arctic soil study turns up surprising results

2010-09-24

(Press-News.org) Across the globe, the diversity of plant and animal species generally increases from the North and South Poles towards the Equator but surprisingly that rule isn't true for soil bacteria, according to a new study by Queen's University biology professor Paul Grogan.

"It appears that the rules determining the patterns for plant and animal diversity are different than the rules for bacteria," says Professor Grogan.

The finding is important because one of the goals in ecology is to explain patterns in the distribution of species and understand the biological and environmental factors that determine why species occur where they do.

Researchers examined the composition and genetic difference of soil bacterial communities from 29 remote arctic locations scattered across Canada, Alaska, Iceland, Greenland and Sweden.

The report also had a second surprising finding. The researchers expected that soil samples taken 20 metres apart would be more similar in terms of bacterial diversity than soil samples taken 5,500 kilometres apart because, in theory, plant or animal communities from nearby locations are likely to be more genetically similar than those from distant locations.

Generally, they found that each soil sample contained thousands of bacterial types, about 50 per cent of which were unique to each sample.

"It turns out that there is no similarity pattern in relation to distance at all, even in comparing side-by-side samples with samples taken from either side of a continent – this really amazed me," says Professor Grogan.

INFORMATION:

The research team included researchers from Queen's and the University of Colorado.

The findings have been accepted for publication in the journal Environmental Microbiology.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2010-09-24

A new technique pioneered at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) is improving the detection and monitoring of insecticide resistance in field populations of an important malaria-carrying mosquito.

Researchers at LSTM, led by Dr Charles Wondji have developed a new technique which encourages the female Anopheles funestus mosquitoes to lay eggs which are then reared into adult mosquitoes to provide sufficient numbers to determine levels of insecticide resistance and to characterise the underlying mechanisms.

Explaining the significance, John Morgan, who designed ...

2010-09-24

Researchers at Mount Sinai School of Medicine have found that the costs of care for patients with cancer who disenrolled from hospice were nearly five times higher than for patients who remained with hospice. Patients who disenroll from hospice are far more likely to use emergency department care and be hospitalized. The results are published in the October 1 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Led by Melissa D.A. Carlson, PhD, Assistant Professor of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, and Elizabeth H. Bradley, PhD, Professor of Public Health at Yale University, ...

2010-09-24

A non-stick coating for a substance found in semen dramatically lowers the rate of infection of immune cells by HIV a new study has found.

The new material is a potential ingredient for microbicides designed to reduce transmission of HIV, a team from the University of Rochester Medical Center and the University of California, San Diego reports in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

The coating clings to fibrous strings and mats of protein called SEVI–for semen-derived enhancer of viral infection–which was first discovered just three years ago. ...

2010-09-24

Like a well-crafted football play designed to block the opposing team's offensive drive to the end zone, the body constantly executes complex 'plays' or sequences of events to initiate, or block, different actions or functions.

Scientists at the University of Rochester Medical Center recently discovered a potential molecular playbook for blocking cardiac hypertrophy, the unwanted enlargement of the heart and a well-known precursor of heart failure. Researchers uncovered a specific molecular chain of events that leads to the inhibition of this widespread risk factor. ...

2010-09-24

Troy, N.Y. – Individuals within a networked system coordinate their activities by communicating to each other information such as their position, speed, or intention. At first glance, it seems that more of this communication will increase the harmony and efficiency of the network. However, scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that this is only true if the communication and its subsequent action are immediate.

Using statistical physics and network science, the researchers were able to find something very fundamental about synchronization and coordination: ...

2010-09-24

In research led by a Saint Louis University surgeon, investigators found that women who give birth after suffering pelvic fractures receive C-sections at more than double normal rates despite the fact that vaginal delivery after such injuries is possible. In addition, women reported lingering, yet often treatable, symptoms following their pelvic fracture injuries, from urinary complications to post-traumatic stress disorder.

The study, published in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, retrospectively reviewed the cases of 71 women who had suffered pelvic fractures, ...

2010-09-24

PASADENA, Calif.—Computers, light bulbs, and even people generate heat—energy that ends up being wasted. With a thermoelectric device, which converts heat to electricity and vice versa, you can harness that otherwise wasted energy. Thermoelectric devices are touted for use in new and efficient refrigerators, and other cooling or heating machines. But present-day designs are not efficient enough for widespread commercial use or are made from rare materials that are expensive and harmful to the environment.

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) ...

2010-09-24

RENO, Nev. – Like the little engine that could, the University of Nevada, Reno experiment to transform wastewater sludge to electrical power is chugging along, dwarfed by the million-gallon tanks, pipes and pumps at the Truckee Meadows Water Reclamation Facility where, ultimately, the plant's electrical power could be supplied on-site by the process University researchers are developing.

"We are very pleased with the results of the demonstration testing of our research," Chuck Coronella, principle investigator for the research project and an associate professor of chemical ...

2010-09-24

WASHINGTON– In recent decades, the rate at which humans worldwide are pumping dry the vast underground stores of water that billions depend on has more than doubled, say scientists who have conducted an unusual, global assessment of groundwater use.

These fast-shrinking subterranean reservoirs are essential to daily life and agriculture in many regions, while also sustaining streams, wetlands, and ecosystems and resisting land subsidence and salt water intrusion into fresh water supplies. Today, people are drawing so much water from below that they are adding enough ...

2010-09-24

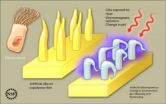

University of Southern Mississippi scientists recently imitated Mother Nature by developing, for the first time, a new, skinny-molecule-based material that resembles cilia, the tiny, hair-like structures through which organisms derive smell, vision, hearing and fluid flow.

While the new material isn't exactly like cilia, it responds to thermal, chemical, and electromagnetic stimulation, allowing researchers to control it and opening unlimited possibilities for future use.

This finding is published in today's edition of the journal Advanced Functional Materials. The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Arctic soil study turns up surprising results