(Press-News.org) A pioneering class of drugs that target cancers with mutations in the BRCA breast cancer genes could also work against tumours with another type of genetic fault, a new study suggests.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that errors in a gene called CLBC leave cancer cells vulnerable to PARP inhibitor drugs. Around 2 per cent of all tumours have defects in CLBC.

The study, which was carried out in collaboration with colleagues in Denmark and the Czech Republic, was funded in the UK by the European Union, and was published today (Thursday) in the journal Oncotarget.

Olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, became the first cancer drug targeted at an inherited genetic fault to reach the market when it was approved in December for use in ovarian cancer patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Its development was underpinned by research at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR).

Using an approach known as RNA interference screening - which 'silences' genes to analyse their function - researchers systematically tested which of the 25,000 genes in the human genome affected the response of cancer cells to olaparib.

The ICR team found that cancer cells with a defect in the CBLC gene were as sensitive to the drug as those with a faulty BRCA2 gene.

By analysing the molecular processes that the CBLC gene controls, researchers found that it normally allows cells to repair damaged DNA by fixing broken DNA strands back together.

This finding indicates that a flaw in DNA repair mechanisms explains the sensitivity of CBLC-defective cancer cells to PARP inhibitors - which knock out the action of another DNA repair mechanism.

DNA repair is often disrupted in cancer cells, which sacrifice genetic stability as they gain mutations that allow them to divide uncontrollably. These cancer cells may be particularly vulnerable to drugs to block DNA repair proteins, since they may lack any alternative functioning repair systems to fall back on.

Study co-leader Dr Chris Lord, Team Leader in Gene Function at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

"Our study has found that defects in a rather poorly studied DNA repair gene called CLBC seem to greatly increase sensitivity to olaparib, a PARP inhibitor which is currently licensed only for BRCA-mutated cancer.

"PARP inhibitors are an exciting new class of cancer drug. Understanding why different types of tumour cells respond to PARP inhibitors will play a critical part in making sure these new drugs are used in the most effective way."

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

"The development of PARP inhibitors is a UK success story, with collaboration between ICR academics, companies, charities and the NHS leading to trials in BRCA-mutated cancers and the licensing of olaparib only a few months ago."

"This new study adds to evidence that PARP inhibitors can be effective in a broader group of patients than those with BRCA mutations, and could lead to them being used more widely in patients with other kinds of faults in DNA repair."

INFORMATION:

Notes to editors

For more information contact Henry French on 020 7153 5582 / henry.french@icr.ac.uk. For enquiries out of hours, please call 07595 963 613.

The Institute of Cancer Research, London, is one of the world's most influential cancer research institutes.

Scientists and clinicians at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) are working every day to make a real impact on cancer patients' lives. Through its unique partnership with The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and 'bench-to-bedside' approach, the ICR is able to create and deliver results in a way that other institutions cannot. Together the two organisations are rated in the top four cancer centres globally.

The ICR has an outstanding record of achievement dating back more than 100 years. It provided the first convincing evidence that DNA damage is the basic cause of cancer, laying the foundation for the now universally accepted idea that cancer is a genetic disease. Today it leads the world at isolating cancer-related genes and discovering new targeted drugs for personalised cancer treatment.

As a college of the University of London, the ICR provides postgraduate higher education of international distinction. It has charitable status and relies on support from partner organisations, charities and the general public.

The ICR's mission is to make the discoveries that defeat cancer. For more information visit http://www.icr.ac.uk

Are humans born with the ability to solve problems or is it something we learn along the way? A research group at the Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, is working to find answers to this question.

The research group has developed a computer game called Quantum Moves, which has been played 400,000 times by ordinary people. This has provided unique and deep insight into the human brain's ability to solve problems. The game involves moving atoms around on the screen and scoring points by finding the best way to do so.

In this way, ordinary people ...

Scientists at the University of Cambridge have successfully created 'mini-lungs' using stem cells derived from skin cells of patients with cystic fibrosis, and have shown that these can be used to test potential new drugs for this debilitating lung disease.

The research is one of a number of studies that have used stem cells - the body's master cells - to grow 'organoids', 3D clusters of cells that mimic the behaviour and function of specific organs within the body. Other recent examples have been 'mini-brains' to study Alzheimer's disease and 'mini-livers' to model ...

Women who received a text message reminding them about their breast cancer screening appointment were 20 per cent more likely to attend than those who were not texted, according to a study published in the British Journal of Cancer today (Thursday)*.

Researchers, funded by the Imperial College Healthcare Charity, trialled text message reminders for women aged 47-53 years old who were invited for their first appointment for breast cancer screening.

The team compared around 450 women who were sent a text with 435 women who were not texted**. It found that 72 per cent ...

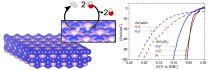

PISCATAWAY, N.J. (March 18, 2015) - New research published by Rutgers University chemists has documented significant progress confronting one of the main challenges inhibiting widespread utilization of sustainable power: Creating a cost-effective process to store energy so it can be used later.

"We have developed a compound, Ni5P4 (nickel-5 phosphide-4), that has the potential to replace platinum in two types of electrochemical cells: electrolyzers that make hydrogen by splitting water through hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) powered by electrical energy, and fuel cells ...

The number of people living with cystic fibrosis into adulthood in the UK is expected to increase dramatically - by as much as 80 per cent - by 2025, according to a Europe-wide survey, the UK end of which was led by Queen's University Belfast.

People living with cystic fibrosis have previously had low life expectancy, but improvements in treatments in the last three decades have led to an increase in survival with almost all children now living to around 40 years. In countries where reliable data exists, the average rise in the number of adults with CF is expected to be ...

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry reports that following military parents' return from combat deployment, their children show increased visits for mental healthcare, physical injury, and child maltreatment consults, compared to children whose parents have not been deployed. The same types of healthcare visits were also found to be significantly higher for children of combat-injured parents.

Children of deployed parents are known to have increased mental healthcare needs, and be at increased risk for child ...

When cancer strikes, it may be possible for patients to fight back with their own defenses, using a strategy known as immunotherapy. According to a new study published in Nature, researchers have found a way to enhance the effects of this therapeutic approach in glioblastoma, a deadly type of brain cancer, and possibly improve patient outcomes. The research was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) as well as the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which are part of the National Institutes of Health.

"The promise of dendritic cell-based ...

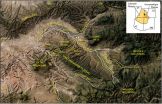

Boulder, Colo., USA - Unaweep Canyon is a puzzling landscape -- the only canyon on Earth with two mouths. First formally documented by western explorers mapping the Colorado Territory in the 1800s, Unaweep Canyon has inspired numerous hypotheses for its origin. This new paper for Geosphere by Gerilyn S. Soreghan and colleagues brings together old and new geologic data of this region to further the hypothesis that Unaweep Canyon was formed in multiple stages.

The inner gorge originated ~300 million years ago, was buried, was then revealed about five million years ago when ...

Latinos are the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, and it's expected that by 2050 they will comprise almost 30 percent of the U.S. population. Yet they are also the most underserved by health care and health insurance providers.

Latinos' low rates of insurance coverage and poor access to health care strongly suggest a need for better outreach by health care providers and an improvement in insurance coverage. Although the implementation of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 seems to have helped (approximately 25 percent of those eligible for coverage under ...

Could our reaction to an image of an overweight or obese person affect how we perceive odor? A trio of researchers, including two from UCLA, says yes.

The researchers discovered that visual cues associated with overweight or obese people can influence one's sense of smell, and that the perceiver's body mass index matters, too. Participants with higher BMI tended to be more critical of heavier people, with higher-BMI participants giving scents a lower rating when scent samples were matched with an obese or overweight individual.

The findings, published online in the ...