Russian chemists developed polymer cathodes for ultrafast batteries

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) Scientists are searching for lithium technology alternatives in the face of the surging demand for lithium-ion batteries and limited lithium reserves. Russian researchers from Skoltech, D. Mendeleev University, and the Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics of RAS have synthesized and tested new polymer-based cathode materials for lithium dual-ion batteries. The tests showed that the new cathodes withstand up to 25,000 operating cycles and charge in a matter of seconds, thus outperforming lithium-ion batteries. The cathodes can also be used to produce less expensive potassium dual-ion batteries. The research was published in the journal Energy Technology.

The amount of electricity consumed worldwide grows by the year, and so does the demand for energy storage solutions since many devices often operate in autonomous mode. Lithium-ion batteries can generate enormous power while showing fairly high discharge and charge rates and storage capacity per unit mass, making them a popular storage device in electronics, electric transport, and global power grids. For instance, Australia is launching a series of large-scale lithium-ion battery storage projects to manage excess solar and wind energy.

If lithium-ion batteries continue to be produced in growing quantities, the world may sooner or later run out of lithium reserves. With Congo producing 60% of cobalt for lithium-ion batteries' cathodes, cobalt prices may skyrocket. The same goes for lithium, as lithium mining's water consumption poses a great challenge for the environment. Therefore, researchers are looking for new energy storage devices relying on more accessible materials while using the same operating principle as lithium-ion batteries.

The team used a promising post-lithium dual-ion technology based on the electrochemical processes involving the electrolyte's anions and cations to attain a manifold increase in lithium-ion batteries' charging rate. Another plus is that the cathode prototypes were made of polymeric aromatic amines synthesized from various organic compounds.

"Our previous research addressed polymer cathodes for ultra-fast high-capacity batteries that can be charged and discharged in a few seconds, but we wanted more," says Filipp A. Obrezkov, a Skoltech Ph.D. student and the first author of the paper. "We used various alternatives, including linear polymers, in which each monomeric unit bonds with two neighbors only. In this study, we went on to study new branched polymers where each unit bonds with at least three other units. Together they form large mesh structures that ensure faster kinetics of the electrode processes. Electrodes made of these materials display even higher charge and discharge rates."

A standard lithium-ion cell is filled with lithium-containing electrolyte and divided into the anode and the cathode by a separator. In a charged battery, the majority of lithium atoms are incorporated in the anode's crystal structure. As the battery discharges, lithium atoms move from the anode to the cathode through the separator. The Russian team studied the dual-ion batteries in which the electrochemical processes involved the electrolyte's cations (i.e., lithium cations) and anions that get in and out of the anode and cathode material's structures, respectively.

Another novel feature is that, in some experiments, the scientists used potassium electrolytes instead of expensive lithium ones to obtain potassium dual-ion batteries.

The team synthesized two novel copolymers of dihydrophenazine with diphenylamine (PDPAPZ) and phenothiazine (PPTZPZ), which they used to produce cathodes. As anodes, they used metallic lithium and potassium. Since the cathode drives the key features of these battery prototypes called half-cells, the scientists assemble them to assess the capabilities of new cathode materials quickly.

While PPTZPZ half-cells showed average performance, PDPAPZ turned out to be more efficient: lithium half-cells with PDPAPZ were fairly quick to charge and discharge while displaying good stability and retaining up to a third of their capacity even after 25,000 operating cycles. If a regular phone battery were as stable, it could be charged and discharged daily for 70 years. PDPAPZ potassium half-cells exhibited a high energy density of 398 Wh/kg. For comparison, the value for common lithium cells is 200-250 Wh/kg, the anode and electrolyte weights included. Thus the Russian team demonstrated that polymer cathode materials could create efficient lithium and potassium dual-ion batteries.

INFORMATION:

Skoltech is a private international university located in Russia. Established in 2011 in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Skoltech is cultivating a new generation of leaders in the fields of science, technology, and business is researching in breakthrough fields, and is promoting technological innovation intending to solve critical problems that face Russia and the world. Skoltech is focusing on six priority areas: data science and artificial intelligence, life sciences, advanced materials and modern design methods, energy efficiency, photonics, and quantum technologies, and advanced research.

Web: https://www.skoltech.ru/.

The D. Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia, a mainstay university for the Russian chemical industry, aims to generate and integrate new knowledge in the industry. This study was performed by the researchers of the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech) and the Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics of RAS, as well as the students of D. Mendeleev University's Institute of Chemistry and Problems of Sustainable Development, with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russia and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR).

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

Having a choice of foods may accelerate aging and shorten the lifespan of fruit flies, according to a study published today in the open-access eLife journal.

While early experiments have shown that calorie restriction can extend lifespan, the current study adds to the growing body of evidence that suggests other diet characteristics besides calories may also influence aging and lead to earlier death.

"It has been recognised for nearly a century that diet modulates aging," says first author Yang Lyu, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, US. "For our study, we wanted to see if having a choice of foods affects metabolism and lifespan in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster."

Lyu ...

2021-01-19

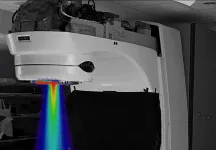

LEBANON, NH - A joint team of researchers from Radiation Oncology at Dartmouth's and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC), Dartmouth Engineering, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Department of Surgery have developed a method to convert a standard linear accelerator (LINAC), used for delivery of radiation therapy cancer treatment, to a FLASH ultra-high-dose rate radiation therapy beam. The work, entitled "Electron FLASH Delivery at Treatment Room Isocenter for Efficient Reversible Conversion of a Clinical LINAC," is newly published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology & Physics.

The exceptionally high dose rate is 3,000 times higher than normal therapy treatment (300 Gray per second vs. 0.1 Gray per second, Gray being a standard ...

2021-01-19

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from the Russian Quantum Center revealed a significant role of nuclear quantum effects in the polarization of alcohol in an external electric field. Their research findings are published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry.

Molecular liquids, such as water or alcohols, are known to be polar. Polarity results from the charge separation mechanism, the microscopic description of which still bears some open questions. In fact, the basic description of the polarization rests on a hundred-years-old concept: the dielectric polarization is connected to the molecular dipole moment due to their hydroxyl ...

2021-01-19

WASHINGTON, Jan. 19, 2020 -- What makes breast milk so good for babies? In this episode of Reactions, our host, Sam, chats with chemist Steven Townsend, Ph.D., who's trying to figure out which sugar molecules in breast milk make it so unique and difficult to mimic: https://youtu.be/o4_npLDyyUw.

INFORMATION:

Reactions is a video series produced by the American Chemical Society and PBS Digital Studios. Subscribe to Reactions at http://bit.ly/ACSReactions and follow us on Twitter @ACSReactions.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS' mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and its people. The Society is a global leader in providing access ...

2021-01-19

Two international studies confirm that for the majority of patients with respiratory infections who lose the sense of smell, this is due to COVID-19. The disease also often results in both loss of taste and the other senses in the mouth. A researcher from Aarhus University has contributed to the new results.

If you have had COVID-19, then forget about enjoying the smell of freshly made coffee. At any rate, two major international studies document that there is frequently a loss of smell and that this often lasts for a long time in cases of COVID-19

Alexander Wieck Fjaeldstad, is associate professor in olfaction and gustation at Aarhus University, and is behind the Danish part of the study.

The study ...

2021-01-19

In a large-scale study of Danish children and young people, researchers from Aarhus University have for the first time found genetic variants that increase the risk of nocturnal enuresis - commonly known as bedwetting or nighttime incontinence. The findings provide completely new insights into the processes in the body causing this widespread phenomenon.

Researchers have long known that nighttime incontinence is a highly heritable condition. Children who wet the bed at night often have siblings or parents who either suffer from or have suffered from the same condition. ...

2021-01-19

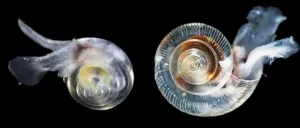

Shelled pteropods, microscopic free-swimming sea snails, are widely regarded as indicators for ocean acidification because research has shown that their fragile shells are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity.

A new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that pteropods sampled off the coasts of Washington and Oregon made thinner shells than those in offshore waters. Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, by a team of Dutch and American scientists, ...

2021-01-19

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory and collaborators at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have discovered a new light-induced switch that twists the crystal lattice of the material, switching on a giant electron current that appears to be nearly dissipationless. The discovery was made in a category of topological materials that holds great promise for spintronics, topological effect transistors, and quantum computing.

Weyl and Dirac semimetals can host exotic, nearly dissipationless, electron conduction properties that take advantage of the unique state in the crystal lattice and electronic structure of the material that protects the electrons from doing so. These anomalous electron transport channels, ...

2021-01-19

Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as ...

2021-01-19

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Russian chemists developed polymer cathodes for ultrafast batteries