New Tel Aviv University study reveals 'Achilles' heel' of cancer cells

Research could lead to development of future drugs to eliminate the cells

2021-01-27

(Press-News.org) What makes cancer cells different from ordinary cells in our bodies? Can these differences be used to strike at them and paralyze their activity? Cancer researchers have been debating this question since the mid-19th century.

A new study from Tel Aviv University (TAU) shows, for the first time, how an abnormal number of chromosomes (aneuploidy) -- a unique characteristic of cancer cells that researchers have known about for decades -- could become a weak point for these cells. The study could lead to the development of future drugs that will use this vulnerability to eliminate the cancer cells.

The study was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Uri Ben-David of TAU's Sackler Faculty of Medicine, in collaboration with six laboratories from four other countries. It was published in the journal Nature on January 27, 2021.

Aneuploidy is a hallmark of cancer. Normal human cells contain two sets of 23 chromosomes each, one from the father and one from the mother. But aneuploid cells have a different number of chromosomes. When aneuploidy forms in cancer cells, the cells not only "tolerate" it, but it can even advance the progression of the disease. The relationship between aneuploidy and cancer was discovered over a century ago, long before it was known that cancer was a genetic disease and even before the discovery of DNA as hereditary material.

According to Dr. Ben-David, aneuploidy is the most common genetic change in cancer. Approximately 90% of solid tumors, such as breast cancer and colon cancer, and 75% of blood cancers are aneuploid in nature. But researchers' understanding of the how aneuploidy contributes to the development and spread of cancer has been limited.

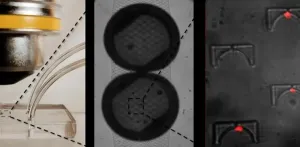

In the study, the researchers used advanced bioinformatics methods to quantify aneuploidy in approximately 1,000 cancer cell cultures. They then compared the genetic dependency and drug sensitivity of the cells with a high level of aneuploidy to those of the cells with a low level of aneuploidy.

They found that aneuploid cancer cells demonstrate heightened sensitivity to damage to the mitotic checkpoint - a cellular checkpoint that ensures the proper separation of chromosomes during cell division. They also discovered the molecular basis for the heightened sensitivity of aneuploid cancer cells.

The study has important implications for the drug discovery process in personalized cancer medicine. Drugs that delay the separation of chromosomes are undergoing clinical trials, but it is not known which patients will respond to them and which will not. The results of this study suggest that it will be possible to use aneuploidy as a biological marker to identify patients who will respond better to these drugs.

"It should be emphasized that the study was done on cells in a culture and not on cancer patients. In order to translate it to treatment of cancer patients, many more follow-up studies must be performed. Still, even at this stage it is clear that the study could have a number of medical implications," Dr. Ben-David says.

INFORMATION:

ABOUT TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY

Tel Aviv University (TAU) exemplifies the qualities of the city it inhabits -- innovative, fast-paced, exciting, and creative. A globally top-ranked university, a leading research institution, a center of discovery -- TAU embraces a culture and student body that is inquisitive and responsive to pressing issues and world-wide problems. As Israel's largest public institution of higher learning, TAU is home to 30,000 students, including 2,100 international students from over 100 countries. The University encompasses nine faculties, 35 schools, 400 labs, and has 17 affiliated hospitals in its network.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-27

Cells don't express all the genes they contain all the time. The portion of our genome that encodes eye color, for example, doesn't need to be turned on in liver cells. In plants, genes encoding the structure of a flower can be turned off in cells that will form a leaf.

These unneeded genes are kept from becoming active by being stowed in dense chromatin, a tightly packed bundle of genetic material laced with proteins.

In a new study in the journal Nature Communications, biologists from the University of Pennsylvania identify a protein that enables plant cells to reach these otherwise inaccessible genes in order to switch between different identities. Called ...

2021-01-27

Irvine, Calif., Jan. 27, 2021 -- One of President Joe Biden's first post-inauguration acts was to realign the United States with the Paris climate accord, but a new study led by researchers at the University of California, Irvine demonstrates that rising emissions from human land-use will jeopardize the agreement's goals without substantial changes in agricultural practices.

In a paper published today in Nature, the team presented the most thorough inventory yet of land-use contributions to carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (including nitrous oxide and methane) from 1961 to 2017, taking into account emissions from agricultural production activities and modifications to the natural landscape.

"We estimated and attributed global land-use emissions among 229 countries ...

2021-01-27

Gardeners and farmers around the country recognize that crop varieties grow best in certain regions. Most plant species have adapted to their local environments; for example, crop and ornamental seeds sold for the upper Midwest are often very different than those bred for Texas. Identifying and breeding varieties that have high productivity across a range of environments is becoming increasingly important for food, fuel and other applications, and breeders aren't interested in waiting decades to develop new crops.

One example is an ongoing collaborative effort to improve the emerging bioenergy crop ...

2021-01-27

The development of cost-efficient, portable microscopy units would greatly expand their use in remote field locations and in places with fewer resources, potentially leading to easier on-site analysis of contaminants such as E. coli in water sources as well as other practical applications.

Current microscopy systems, like those used to image micro-organisms, are expensive because they are optimized for maximum resolution and minimal deformation of the images the systems produce. But some situations do not require such optimization--for instance, simply detecting the presence of pathogens in water. One potential approach to developing a low-cost portable microscopy system is to use transparent microspheres in combination with affordable ...

2021-01-27

In September, a team led by astronomers in the United Kingdom announced that they had detected the chemical phosphine in the thick clouds of Venus. The team's reported detection, based on observations by two Earth-based radio telescopes, surprised many Venus experts. Earth's atmosphere contains small amounts of phosphine, which may be produced by life. Phosphine on Venus generated buzz that the planet, often succinctly touted as a "hellscape," could somehow harbor life within its acidic clouds.

Since that initial claim, other science teams have cast doubt on the reliability of the phosphine ...

2021-01-27

Car accidents are responsible for approximately a million deaths each year globally. Among the many causes, driving at night, when vision is most limited, leads to accidents with higher mortality rates than accidents during the day. Therefore, improving visibility during night driving is critical for reducing the number of fatal car accidents.

An adaptive driving beam (ADB) can help to some extent. This advanced drive-assist technology for vehicle headlights can automatically adjust the driver's visibility based on the car speed and traffic environment. ADB systems that ...

2021-01-27

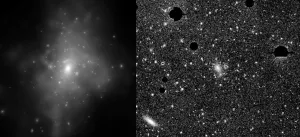

A combination of observational data and sophisticated computer simulations have yielded advances in a field of astrophysics that has languished for half a century. The Dark Energy Survey, which is hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, has published a burst of new results on what's called intracluster light, or ICL, a faint type of light found inside galaxy clusters.

The first burst of new, precision ICL measurements appeared in a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal in April 2019. Another appeared more recently in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. In a surprise finding of the latter, DES physicists discovered new evidence that ICL might provide a new way to measure a mysterious substance called ...

2021-01-27

As surgeons balance the need to control their patients' post-surgery pain with the risk that a routine operation could become the gateway to long-term opioid use or addiction, a new study shows the power of an approach that takes a middle way.

In a new letter in JAMA Surgery, a team from Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan reports on findings from a study of 620 patients who had surgery in hospitals across Michigan, had their painkiller use tracked, and took surveys within one to three months after their operations.

Half of the patients received pre-surgery counseling that emphasized non-opioid pain treatment as their first option. Some patients in this group received small, "just in case" prescriptions, but a third of them didn't receive any opioid prescription ...

2021-01-27

LA JOLLA--A new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) suggests that T cells try to fight SARS-CoV-2 by targeting a broad range of sites on the virus--beyond the key sites on the virus's spike protein. By attacking the virus from many angles, the body has the tools to potentially recognize different SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The new research, published January 27, 2021 in Cell Report Medicine, is the most detailed analysis so far of which proteins on SARS-CoV-2 stimulate the strongest responses from the immune system's "helper" CD4+ T cells and "killer" CD8+ T cells.

"We ...

2021-01-27

INDIANAPOLIS--Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified how breast cancer cells hide from immune cells to stay alive. The discovery could lead to better immunotherapy treatment for patients.

Xinna Zhang, PhD, and colleagues found that when breast cancer cells have an increased level of a protein called MAL2 on the cell surface, the cancer cells can evade immune attacks and continue to grow. The findings are published this month in The Journal of Clinical Investigation and featured on the journal's cover.

The lead author of the study, Zhang is a member of the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New Tel Aviv University study reveals 'Achilles' heel' of cancer cells

Research could lead to development of future drugs to eliminate the cells