(Press-News.org) RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- A team led by a biomedical scientist at the University of California, Riverside, reports a drug -- an estrogen receptor ligand called indazole chloride (IndCl) -- has the potential to improve vision in patients with multiple sclerosis, or MS.

The study, performed on mice induced with a model of MS and the first to investigate IndCl's effect on the pathology and function of the complete afferent visual pathway, is published in Brain Pathology. The afferent visual pathway includes the eyes, optic nerve, and all brain structures responsible for receiving, transmitting, and processing visual information.

In MS, a disease in which the immune system "demyelinates" or eats away at the protective covering of nerves, the initial period of inflammation and demyelination often damages the optic nerve and other parts of the visual system first. As a result, approximately 50% of patients with MS experience optic neuritis -- inflammatory demyelination of the optic nerve -- prior to showing initial symptoms. Almost all MS patients have impaired vision at some point during disease progression. Symptoms can include eye pain, blurred vision, and progressive vision loss that can lead to blindness, among other visual impairments.

The optic nerve, a heavily myelinated bundle of nerves located at the back of the eye, transfers visual information from the retina to the vision centers of the brain through electrical impulses. Myelin acts as an insulating substance that speeds the transmission of these electrical impulses. Partial myelin loss slows transmission of visual information; severe myelin loss may stop the signal altogether.

The researchers used IndCl to assess its impact on demyelinating visual pathway axons. The treatment induced remyelination and mitigated some damage to the axons that resulted in partial functional improvement in vision.

"IndCl has been previously shown in mice to reduce motor disability, increase myelination, and neuroprotection in the spinal cord and corpus callosum," said Seema Tiwari-Woodruff, a professor of biomedical sciences at the UC Riverside School of Medicine and the study's lead author. "Its effects in the visual system, however, were not evaluated until now. Our study shows the optic nerve and optic tract, which undergo significant inflammation, demyelination, and axonal damage, are able to restore some function with IndCl treatment with successful attenuation in inflammation and an increase in remyelination."

The visual pathway in mice is similar to that in humans. The mouse brain is, therefore, an excellent model for scientists to study vision impairment. In the lab, Tiwari-Woodruff and her research group first induced the mouse model of MS. They let the disease progress for about 60 days and when the disease reached a peak between 15 and 21 days, they administered IndCl to half the mice. At the end of the experiment, they performed functional assay to measure the visual electrical signal; and immunohistochemistry to examine the visual pathway. The mice that received the drug showed improvement in myelination, with visual function improving by about 50%.

For Tiwari-Woodruff, the next question is how IndCl treatment induces functional remyelination in the visual pathway. Her lab, in collaboration with the lab of co-author John A. Katzenellenbogen at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is investigating new drugs that are analogues of IndCl.

"Measuring visual function and recovery in the presence of novel therapies can be used to screen more effective therapies that will protect axons, stimulate axon remyelination, and prevent ongoing axon damage," Tiwari-Woodruff said.

Currently approved MS drugs reduce inflammation but do not prevent neurodegeneration or initiate remyelination. Further, they only partially prevent the onset of permanent disability in patients with MS.

"We treated the MS mice with IndCl at peak disease," Tiwari-Woodruff said. "If the brain is highly diseased, some of the axons that could potentially restore visual function are too damaged and will not recover. There's a point of no return. Our paper stresses that to acquire vision improvement, treatment must start early. Early treatment can recover 75%-80% of the original function."

Tiwari-Woodruff stressed that although additional studies are required, the new findings show the dynamics of visual pathway dysfunction and disability in MS mice, along with the importance of early treatment to mitigate axon damage.

"There is a strong and urgent need to find a therapeutic candidate that restores neurological function in patients with MS," Tiwari-Woodruff said. "Therapeutics must target remyelination and prevent further axonal degeneration and neuronal loss. The good estrogens, which have neuroprotective and immunomodulatory benefits, could be candidates for MS treatment."

INFORMATION:

Tiwari-Woodruff and Katzenellenbogen were joined in the study by Maria T. Sekyi, Kelli Lauderdale, Kelley C. Atkinson, Batis Golestany, Hawra Karim, Micah Feri, Joselyn S. Soto, and Cobi Diaz at UCR; Sung Hoon Kim at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and Marianne Cilluffo and Steven Nusinowitz at UCLA. Sekyi, now a former graduate student at UCR, is the first author of the paper.

The study was funded by grants from National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Sekyi was supported by a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship.

The research paper is titled "Alleviation of extensive visual pathway dysfunction by a remyelinating drug in a chronic mouse model of multiple sclerosis."

The University of California, Riverside (http://www.ucr.edu) is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment is more than 25,000 students. The campus opened a medical school in 2013 and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Center. The campus has an annual statewide economic impact of almost $2 billion. To learn more, email news@ucr.edu.

Northwestern University researchers have developed a new approach to quantum device design that has produced the first gain-based long-wavelength infrared (LWIR) photodetector using band structure engineering based on a type-II superlattice material.

This new design, which demonstrated enhanced LWIR photodetection during testing, could lead to new levels of sensitivity for next-generation LWIR photodetectors and focal plane array imagers. The work could have applications in earth science and astronomy, remote sensing, night vision, optical communication, and thermal and medical imaging.

"Our design ...

Oxford, February 2, 2021 - In an upcoming issue of the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, published by Elsevier, undergraduate researchers from the University of Alberta's Radiation Therapy Program in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry describe how LGBTQ2SPIA+ patients face unique cancer risks, including fear of discrimination, higher incidence of certain cancer sites, and lower screening rates, resulting in more cancers detected at later stages.

"I understand that there are different gender pronouns, I do not understand them all."

To discover the knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors of the healthcare professionals treating these patients, the authors surveyed ...

Beaten ballots: political participation dynamics amidst police interventions is the title of the academic article by Toni Rodon and Marc Guinjoan, lecturers of Political Sciences at UPF and the UB, respectively, which seeks to look in greater depth at the effects of police interventions regarding political participation, taking the "repression-mobilization" nexus debate as a starting point.

The study, published recently in the Cambridge University Press journal Political Science Research and Methods, focuses on the analysis of the referendum on independence held in Catalonia on 1 October 2017, when despite the police crackdown, 2,286,217 people voted, representing 44% of ...

Experts predict that autonomous vehicles (AVs) will eventually make our roads safer since the majority of accidents are caused by human error. However, it may be some time before people are ready to put their trust in a self-driving car.

A new study in the journal Risk Analysis found that people are more likely to blame a vehicle's automation system and its manufacturer than its human driver when a crash occurs.

Semi-autonomous vehicles (semi-AVs), which allow humans to supervise the driving and take control of the vehicle, are already on the ...

Recent global calamities - the pandemic, wildfires, floods - are spurring interdisciplinary scientists to nudge aside the fashionable First Law of Geography that dictates "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."

Geography, and by association, ecology, has largely followed what's known as Tobler's Law, which took hold in the early 1970s. But then came the novel coronavirus apparently has leapt from wildlife meat markets in China to the world in a matter of months. Global climate change creates conditions ripe for infernos in the North American west and Australia. ...

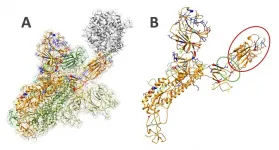

EL PASO, Texas - An effort led by Lin Li, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics at The University of Texas at El Paso, in collaboration with students and faculty from Howard University, has identified key variants that help explain the differences between the viruses that cause COVID-19 and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

A team comprised of researchers from UTEP and the historically Black research university in Washington, D.C., discovered valuable data in comparing the fundamental mechanisms of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and SARS-CoV-2 -- also known as COVID-19 -- to better understand how ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Extensive sea ice covered the world's oceans during the last ice age, which prevented oxygen from penetrating into the deep ocean waters, complicating the relationship between oxygen and carbon, a new study has found.

"The sea ice is effectively like a closed window for the ocean," said Andreas Schmittner, a climate scientist at Oregon State University and co-author on the paper. "The closed window keeps fresh air out; the sea ice acted as a barrier to keep oxygen from entering the ocean, like stale air in a room full of people. If you open the window, oxygen ...

Amazon's search algorithm gives preferential treatment to books that promote false claims about vaccines, according to research by UW Information School Ph.D. student Prerna Juneja and Assistant Professor Tanu Mitra.

Meanwhile, books that debunk health misinformation appear lower in Amazon's search results, where they are less likely to be seen, the researchers wrote in a paper that was recently accepted to CHI, the top annual conference on human-computer interaction.

In their paper, Juneja and Mitra noted that Amazon has faced criticism for not regulating health-related products on its platform. They conducted audits to determine how much health misinformation is present in Amazon's recommendations ...

The lockdowns and reduced societal activity related to the COVID-19 pandemic affected emissions of pollutants in ways that slightly warmed the planet for several months last year, according to new research led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The counterintuitive finding highlights the influence of airborne particles, or aerosols, that block incoming sunlight. When emissions of aerosols dropped last spring, more of the Sun's warmth reached the planet, especially in heavily industrialized nations, such as the United States and Russia, that normally pump high amounts of aerosols into the atmosphere.

"There was a big decline in emissions from the most polluting industries, and that had immediate, short-term effects on temperatures," said ...

Yale researchers are developing a skin cancer treatment that involves injecting nanoparticles into the tumor, killing cancer cells with a two-pronged approach, as a potential alternative to surgery.

The results are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"For a lot of patients, treating skin cancer is much more involved than it would be if there was a way to effectively treat them with a simple procedure like an injection," said Dr. Michael Girardi, professor and vice chair of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study. "That's always been a holy grail in dermatology -- to find a simpler way to treat skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma."

For the treatment, tumors are injected ...