(Press-News.org) A team of engineers and scientists has developed a method of 'multiplying' organoids: miniature collections of cells that mimic the behaviour of various organs and are promising tools for the study of human biology and disease.

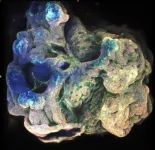

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, used their method to culture and grow a 'mini-airway', the first time that a tube-shaped organoid has been developed without the need for any external support.

Using a mould made of a specialised polymer, the researchers were able to guide the size and shape of the mini-airway, grown from adult mouse stem cells, and then remove it from the mould when it reached the point where it could support itself.

Whereas the organoids currently used in medical research are at the microscopic scale, the method developed by the Cambridge team could make it possible to grow life-sized versions of organs. Their results are reported in the journal Advanced Science.

Organoids are tiny, three-dimensional cell assemblies that mimic the cell arrangement of fully-grown organs. They can be a useful way to study human biology and how it can go wrong in various diseases, and possibly how to develop personalised or regenerative treatments. However, assembling them into larger organ structures remains a challenge.

Other research teams have experimented with 3D printing techniques to develop larger mini-organs, but these often require an external support structure.

"Mini-organs are very small and highly fragile," said Dr Yan Yan Shery Huang from Cambridge's Department of Engineering, who co-led the research. "In order to scale them up, which would increase their usefulness in medical research, we need to find the right conditions to help the cells self-organise."

Huang and her colleagues have proposed a new organoid engineering approach called Multi-Organoid Patterning and Fusion (MOrPF) to grow a miniature version of a mouse airway using stem cells. Using this technique, the scientists achieved faster assembly of organoids into airway tubes with uninterrupted passageways. The mini-airways grown using the MOrPF technique showed potential for scaling up to match living organ structures in size and shape, and retained their shape even in the absence of an external support.

The MOrPF technique involves several steps. First, a polymer mould - like a miniature version of a cake or jelly mould - is used to shape a cluster of many small organoids. The cluster is released from the mould after one day, and then grown for a further two weeks. The cluster becomes one single tubular structure, covered by an outer layer of airway cells. The moulding process is just long enough for the outer layer of the cells to form an envelope around the entire cluster. During the two weeks of further growth, the inner walls gradually disappear, leading to a hollow tubular structure.

"Gradual maturation of the cells is really important," said Dr Joo-Hyeon Lee from Cambridge's Wellcome - MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, who co-led the research. "The cells need to be well-organised before we can release them so that the structures don't collapse."

The organoid cluster can be thought of like soap bubbles, initially packed together to form to the shape of the mould. In order to fuse into a single gigantic bubble from the cluster of compressed bubbles, the inner walls need to be broken down. In the MOrPF process, the fused organoid clusters are released from the mould to grow in floating, scaffold-free conditions, so that the cells forming the inner walls of the fused cluster can be taken out of the cluster. The mould can be made into different sizes or shapes, so that the researchers can pre-determine the shape of the finished mini-organ.

"The interesting thing is, if you think about the soap bubbles, the resulting big bubble is always spherical, but the special mechanical properties of the cell membrane of organoids make the resulting fused shape preserve the shape of the mould," said co-author Professor Eugene Terentjev from Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory.

The team say their method closely approximated the natural process of organ tube formation in some animal species. They are hopeful that their technique will help create biomimetic organs to facilitate medical research.

The researchers first plan to use their method to build a three-dimensional 'organ on a chip', which enables real-time continuous monitoring of cells, and could be used to develop new treatments for disease while reducing the number of animals used in research. Eventually, the technique could also be used with stem cells taken from a patient, in order to develop personalised treatments in future.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported in part by the European Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society.

DANVILLE, Pa. - Researchers at Geisinger have found that a computer algorithm developed using echocardiogram videos of the heart can predict mortality within a year.

The algorithm--an example of what is known as machine learning, or artificial intelligence (AI)--outperformed other clinically used predictors, including pooled cohort equations and the Seattle Heart Failure score. The results of the study were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

"We were excited to find that machine learning can leverage unstructured datasets such as medical images and videos to improve on a wide range of clinical prediction models," said Chris Haggerty, Ph.D., co-senior author and assistant ...

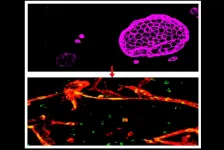

A type of cell derived from human stem cells that has been widely used for brain research and drug development may have been leading researchers astray for years, according to a study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The cell, known as an induced Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (iBMEC), was first described by other researchers in 2012, and has been used to model the special lining of capillaries in the brain that is called the "blood-brain barrier." Many brain diseases, including brain cancers as well as degenerative ...

Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA ...

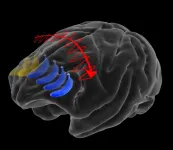

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

What The Study Did: This observational study compared different measures of prediabetes and the risk of progression to diabetes among adults age 71 to 90.

Authors: Mary R. Rooney, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed what percentage of the Virginia population had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 after the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the U.S.

Authors: Eric R. Houpt, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35234)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for ...

If temperature varies strongly from day to day, the economy grows less. Through these seemingly small variations climate change may have strong effects on economic growth. This shows data analyzed by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Columbia University and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC). In a new study in Nature Climate Change, they juxtapose observed daily temperature changes with economic data from more than 1,500 regions worldwide over 40 years - with startling results.

"We ...