The study appears online in the journal Neuro-Oncology Advances.

Average overall survival for all patients in the study was about 15 months after diagnosis. Those receiving the chemotherapy drug temozolomide in the morning had an average overall survival of about 17 months post diagnosis, compared with an average overall survival of about 13½ months for those taking the drug in the evening, a statistically significant difference of about 3½ months.

"We are working hard to develop better treatments for this deadly cancer, but even so, the best we can do right now is prolong survival and try to preserve quality of life for our patients," said co-senior author and neuro-oncologist Jian L. Campian, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine at the School of Medicine. "These results are exciting because they suggest we can extend survival simply by giving our standard chemotherapy in the morning."

Co-senior authors Joshua B. Rubin, MD, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and of neuroscience at the School of Medicine, and Erik D. Herzog, PhD, the Viktor Hamburger Distinguished Professor and a professor of biology in Arts & Sciences, developed a collaboration to study circadian rhythms and their effect on glioblastoma. Rubin and Herzog published studies in which they analyzed mouse models of glioblastoma and found improved effectiveness for temozolomide when given in the morning.

"In my lab, we were studying daily rhythms in astrocytes, a cell type found in the healthy brain," Herzog said. "We discovered some cellular events in healthy cells varied with time of day. Working with Dr. Rubin, we asked if glioblastoma cells also have daily rhythms. And if so, does this make them more sensitive to treatment at certain times? Very few clinical trials consider time of day even though they target a biological process that varies with time of day and with a drug that is rapidly cleared from the body. We will need clinical trials to verify this effect, but evidence so far suggests that the standard-of-care treatment for glioblastoma over the past 20 years could be improved simply by asking patients to take the approved drug in the morning."

In the current study, the researchers -- led by co-first authors Anna R. Damato, a graduate student in neuroscience in the Division of Biology & Biomedical Sciences, and Jingqin (Rosy) Luo, PhD, an associate professor of surgery in the Division of Public Health Sciences and co-director of Siteman Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource -- also observed that among a subset of patients with what are called MGMT methylated tumors, the improved survival with morning chemotherapy was more pronounced. Patients with this tumor type tend to respond better to temozolomide in general. For the 56 patients with MGMT methylated tumors, average overall survival was about 25½ months for those taking the drug in the morning and about 19½ months for those taking it in the evening, a difference of about six months, which was statistically significant.

"The six-month difference was quite impressive," Campian said. "Temozolomide was approved to treat glioblastoma in 2005 based on a 10-week improvement in survival. So, any improvement in survival beyond two months is quite meaningful."

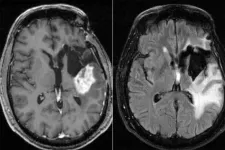

In this retrospective study, the researchers analyzed data from 166 patients with glioblastoma who were treated at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine between January 2010 and December 2018. All patients received the standard of care for glioblastoma. They underwent surgery to remove as much of each tumor as possible and then received radiation therapy along with the chemotherapy drug temozolomide. After the radiation and temozolomide regimen was complete, patients continued taking a maintenance dose of temozolomide -- taken as an oral capsule -- either in the morning or evening, depending on the preference of their oncologists.

"Until now, we have never considered that the timing of temozolomide might be important, so it's up to the treating physician to advise the patient on when to take it," said Campian, who treats patients at the Brain Tumor Center at Siteman. "Many oncologists give it in the evening because patients tend to report fewer side effects then. We saw that in our study as well. But it could be that the increased side effects -- which we can manage with other therapies -- are a sign that the drug is working more effectively."

Added Damato: "There have been screens of different drugs given to cells at different times of day, and huge percentages of these drugs are shown to have time-of-day dependent effects on cell survival. For example, how the drug is absorbed might change throughout the day. So, side effects could change throughout the day."

Campian cautioned that this was a relatively small retrospective analysis. She and her colleagues are conducting a clinical trial in which newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients are randomly assigned to receive temozolomide in either the morning or evening. Such trials will be needed to establish whether treatment timing can truly improve survival for glioblastoma patients.

"There have been no new drugs approved for glioblastoma in over a decade," Luo said. "That makes it necessary to think about other possible changes that make a drug more efficacious. Chronotherapy -- or the timed delivery of drugs, based on circadian rhythms -- is becoming a popular topic. It's practical and realizable to implement chronotherapy to optimize existing drugs and treatments."

INFORMATION:

Campian, Rubin, Herzog and Luo also are research members of Siteman Cancer Center.

This work was supported by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center Siteman Investment Program through funding from The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the Barnard Trust; The Children's Discovery Institute; and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers P30CA091842 and F31CA250161.

Damato AR, Luo J, Katumba RGN, Talcott GR, Rubin JB, Herzog ED, Campian JL. Temozolomide chronotherapy in patients with glioblastoma: a retrospective single institute study. Neuro-Oncology Advances. March 2, 2021.

Washington University School of Medicine's 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, consistently ranking among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.