(Press-News.org) Despite being home to the earliest signs of modern human behaviour, early evidence of burials in Africa are scarce and often ambiguous. Therefore, little is known about the origin and development of mortuary practices in the continent of our species' birth. A child buried at the mouth of the Panga ya Saidi cave site 78,000 years ago is changing that, revealing how Middle Stone Age populations interacted with the dead.

Panga ya Saidi has been an important site for human origins research since excavations began in 2010 as part of a long-term partnership between archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Jena, Germany) and the National Museums of Kenya (Nairobi).

"As soon as we first visited Panga ya Saidi, we knew that it was special," says Professor Nicole Boivin, principal investigator of the original project and director of the Department of Archaeology at the MPI for the Science of Human History. "The site is truly one of a kind. Repeated seasons of excavation at Panga ya Saidi have now helped to establish it as a key type site for the East African coast, with an extraordinary 78,000-year record of early human cultural, technological and symbolic activities."

Portions of the child's bones were first found during excavations at Panga ya Saidi in 2013, but it wasn't until 2017 that the small pit feature containing the bones was fully exposed. About three meters below the current cave floor, the shallow, circular pit contained tightly clustered and highly decomposed bones, requiring stabilisation and plastering in the field.

"At this point, we weren't sure what we had found. The bones were just too delicate to study in the field," says Dr. Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya. "So we had a find that we were pretty excited about - but it would be a while before we understood its importance."

Human remains discovered in the lab

Once plastered, the cast remains were brought first to the National Museum in Nairobi and later to the laboratories of the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain, for further excavation, specialised treatment and analysis.

Two teeth, exposed during initial laboratory excavation of the sediment block, led the researchers to suspect that the remains could be human. Later work at CENIEH confirmed that the teeth belonged to a 2.5- to 3-year-old human child, who was later nicknamed 'Mtoto,' meaning 'child' in Swahili.

Over several months of painstaking excavation in CENIEH's labs, spectacular new discoveries were made. "We started uncovering parts of the skull and face, with the intact articulation of the mandible and some unerupted teeth in place," explains Professor María Martinón-Torres, director at CENIEH. "The articulation of the spine and the ribs was also astonishingly preserved, even conserving the curvature of the thorax cage, suggesting that it was an undisturbed burial and that the decomposition of the body took place right in the pit where the bones were found."

Microscopic analysis of the bones and surrounding soil confirmed that the body was rapidly covered after burial and that decomposition took place in the pit. In other words, Mtoto was intentionally buried shortly after death.

Researchers further suggested that Mtoto's flexed body, found lying on the right side with knees drawn toward the chest, represents a tightly shrouded burial with deliberate preparation. Even more remarkable, notes Martinón-Torres, is that "the position and collapse of the head in the pit suggested that a perishable support may have been present, such as a pillow, indicating that the community may have undertaken some form of funerary rite."

Burials in modern humans and Neanderthals

Luminescence dating securely places Mtoto's at 78,000 years ago, making it the oldest known human burial in Africa. Later interments from Africa's Stone Age also include young individuals - perhaps signaling special treatment of the bodies of children in this ancient period.

The human remains were found in archaeological levels with stone tools belonging to the African Middle Stone Age, a distinct type of technology that has been argued to be linked to more than one hominin species.

"The association between this child's burial and Middle Stone Age tools has played a critical role in demonstrating that Homo sapiens was, without doubt, a definite manufacturer of these distinctive tool industries, as opposed to other hominin species," notes Ndiema.

Though the Panga ya Saidi find represents the earliest evidence of intentional burial in Africa, burials of Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia range back as far as 120,000 years and include adults and high proportion of children and juveniles. The reasons for the comparative lack of early burials in Africa remain elusive, perhaps owing to differences in mortuary practices or the lack of field work in large portions of the African continent.

"The Panga ya Saidi burial shows that inhumation of the dead is a cultural practice shared by Homo sapiens and Neanderthals," notes Professor Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute in Jena. "This find opens up questions about the origin and evolution of mortuary practices between two closely related human species, and the degree to which our behaviours and emotions differ from one another."

INFORMATION:

AMHERST, Mass. - The world is currently on track to exceed three degrees Celsius of global warming, and new research led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Rob DeConto, co-director of the School of Earth & Sustainability, shows that such a scenario would drastically accelerate the pace of sea-level rise by 2100. If the rate of global warming continues on its current trajectory, we will reach a tipping point by 2060, past which these consequences would be "irreversible on multi-century timescales."

The new paper, published today in Nature, models the impact of several different warming scenarios on the Antarctic Ice Sheet, including the Paris Agreement target of two degrees Celsius of warming, an aspirational 1.5 degree scenario, ...

In 1 to 2 percent of cancer cases, the primary site of tumor origin cannot be determined. Because many modern cancer therapeutics target primary tumors, the prognosis for a cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is poor, with a median overall survival of 2.7-to-16 months. In order to receive a more specific diagnosis, patients often must undergo extensive diagnostic workups that can include additional laboratory tests, biopsies and endoscopy procedures, which delay treatment. To improve diagnosis for patients with complex metastatic cancers, especially those in low-resource settings, researchers from the Mahmood Lab at the Brigham and Women's Hospital developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system that uses routinely acquired histology slides to accurately find the origins of metastatic ...

The Antarctic ice sheet is much less likely to become unstable and cause dramatic sea-level rise in upcoming centuries if the world follows policies that keep global warming below a key END ...

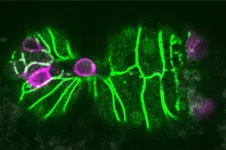

Mitochondria either split in half to multiply within the cell, or cut off their ends to get rid of damaged material. That's the take-away message from EPFL biophysicists in their latest research investigating mitochondrial fission. It's a major departure from the classical textbook explanation of the life cycle of this well-known organelle, the powerhouse of the cell. The results are published today in Nature.

"Until this study, it was poorly understood how mitochondria decide where and when to divide," says EPFL biophysicist Suliana Manley and senior author of the study.

The big question : regulating mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is important for the proliferation of mitochondria, which is fundamental for cellular growth. As a cell gets bigger, ...

The discovery of the earliest human burial site yet found in Africa, by an international team including several CNRS researchers1, has just been announced in the journal Nature. At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, north of Mombasa, the body of a three-year-old, dubbed Mtoto (Swahili for 'child') by the researchers, was deposited and buried in an excavated pit approximately 78,000 years ago. Through analysis of sediments and the arrangement of the bones, the research team showed that the body had been protected by being wrapped in a shroud made of perishable material, and that the head had likely rested on an object also of perishable material. Though there are no signs of offerings or ochre, both common at more recent burial ...

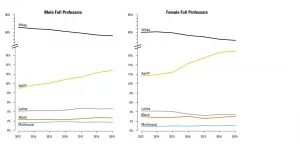

Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits. ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that ...

What The Study Did: This study analyzed changes in Medicaid enrollment for all 50 states and the District of Columbia during the first nine months of last year during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Peggah Khorrami, M.P.H., of the Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9463)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Exeter scientists have discovered a simple, efficient way to recreate the early structure of the human embryo from stem cells in the laboratory. The new approach unlocks news ways of studying human fertility and reproduction.

Stem cells have the ability to turn into different types of cell. Now, in research published in Cell Stem Cell and funded by the Medical Research Council, scientists at the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, working with colleagues from the University of Cambridge, have developed a method to organise lab-grown stem cells into an accurate model of the first stage of human embryo development.

The ability to create artificial ...

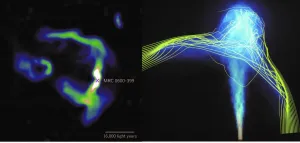

New observations and simulations show that jets of high-energy particles emitted from the central massive black hole in the brightest galaxy in galaxy clusters can be used to map the structure of invisible inter-cluster magnetic fields. These findings provide astronomers with a new tool for investigating previously unexplored aspects of clusters of galaxies.

As clusters of galaxies grow through collisions with surrounding matter, they create bow shocks and wakes in their dilute plasma. The plasma motion induced by these activities can drape intra-cluster magnetic ...