Cardiovascular disease could be diagnosed earlier with new glowing probe

2021-05-05

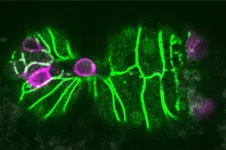

(Press-News.org) Researchers have created a probe that glows when it detects an enzyme associated with issues that can lead to blood clots and strokes.

The team of researchers, from the Department of Chemistry and the National Lung and Heart Institute at Imperial College London, demonstrated that their probe quickly and accurately detects the enzyme in modified E. Coli cells.

They are now expanding this proof-of-concept study, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF), with the hope of creating rapid tests for cardiovascular problems and a new way to track long-term conditions.

The build-up of plaque in the arteries - known as atherosclerosis - can lead to coronary artery disease and stroke, and is one of the leading causes of death in the Western world.

As atherosclerosis progresses, intraplaque haemorrhages (IPHs) can occur when portions of the plaque break away from the artery walls. These events can lead to the formation of more vulnerable plaques and blood clots, restricting blood flow to the heart and the brain and potentially leading to chronic diseases or catastrophic events like strokes.

Detecting IPHs and their impacts would therefore provide a warning system and allow early diagnosis of vascular conditions. The research team designed a chemical probe that can detect rises in levels of an enzyme that accompanies IPHs and even plaque instabilities that precede IPHs.

Study co-lead Professor Nicholas Long, from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial, said: "Progress in the field of early cardiovascular disease has been rather limited and slow-paced but this new probe, and others that we are developing, will go a long way to addressing this by providing real-time and easily measured responses to diagnostic enzymes."

Study co-lead Dr Joe Boyle, from the National Heart and Lung Institute, added: "Ultimately, these probes could provide the basis for diagnostic tests at the GP, ambulances or in hospitals for quick identification of cardiovascular diseases. The probes could also provide real-time analysis of the underpinning biological processes involved in vascular disease, providing new insights and potentially new ways to track the progress of chronic disease."

The team's probe works by detecting an enzyme that is released in large quantities during IPHs, called heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). Previous attempts to screen for HO-1 have been unreliable and cannot be used to detect real-time changes, but the new probe addresses both these issues.

The probe is made up of two components that can host fluorescent (glowing) molecules - one 'donor' that transfers the fluorescent molecules to the 'acceptor' component. When the probe comes into contact with HO-1, the bond between the two components is severed, leading to the build-up of the fluorescent molecules in the donor component.

This build-up causes an increase in the fluorescence intensity of the probe that can be detected using spectroscopy. In tests using modified E. coli cells containing human HO-1, the team detected a six-fold increase in the fluorescence of the probe.

Professor James Leiper, associate medical director at the BHF, said: "Current methods to detect IPH rely on hospital-based imaging techniques that are both time consuming and expensive. The current technology aims to produce a fast and sensitive diagnostic test that can be used at the time that a patient first presents with symptoms to allow early detection of IPH. Use of such a test would allow for more rapid treatment and improved outcomes for patients suffering from IPH."

The team are now extending their studies to mammal and human cells. They have recently patented their probe and have received funding from the British Heart Foundation to make a new generation of probes for other cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and to carry out more in-depth biological investigations of the underlying mechanisms.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-05

Biodiversity is of crucial importance to the marine ecosystem. The prohibition of trawling activities in the Hong Kong marine environment for two and a half years has significantly improved biodiversity, an inter-university study led by City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has found. Research results showed that the trawl ban could restore and conserve biodiversity in tropical coastal waters.

The research team was led by Professor Kenneth Leung Mei-yee, CityU's Director of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution (SKLMP) and Chair Professor in the Department ...

2021-05-05

Researchers at CRANN (The Centre for Research on Adaptive Nanostructures and Nanodevices), and the School of Physics at Trinity College Dublin, today announced that a magnetic material developed at the Centre demonstrates the fastest magnetic switching ever recorded.

The team used femtosecond laser systems in the Photonics Research Laboratory at CRANN to switch and then re-switch the magnetic orientation of their material in trillionths of a second, six times faster than the previous record, and a hundred times faster than the clock speed of a personal computer.

This discovery demonstrates the potential of the material for a new generation of energy efficient ultra-fast computers and data storage systems.

The researchers ...

2021-05-05

Despite being home to the earliest signs of modern human behaviour, early evidence of burials in Africa are scarce and often ambiguous. Therefore, little is known about the origin and development of mortuary practices in the continent of our species' birth. A child buried at the mouth of the Panga ya Saidi cave site 78,000 years ago is changing that, revealing how Middle Stone Age populations interacted with the dead.

Panga ya Saidi has been an important site for human origins research since excavations began in 2010 as part of a long-term partnership between archaeologists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human ...

2021-05-05

AMHERST, Mass. - The world is currently on track to exceed three degrees Celsius of global warming, and new research led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Rob DeConto, co-director of the School of Earth & Sustainability, shows that such a scenario would drastically accelerate the pace of sea-level rise by 2100. If the rate of global warming continues on its current trajectory, we will reach a tipping point by 2060, past which these consequences would be "irreversible on multi-century timescales."

The new paper, published today in Nature, models the impact of several different warming scenarios on the Antarctic Ice Sheet, including the Paris Agreement target of two degrees Celsius of warming, an aspirational 1.5 degree scenario, ...

2021-05-05

In 1 to 2 percent of cancer cases, the primary site of tumor origin cannot be determined. Because many modern cancer therapeutics target primary tumors, the prognosis for a cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is poor, with a median overall survival of 2.7-to-16 months. In order to receive a more specific diagnosis, patients often must undergo extensive diagnostic workups that can include additional laboratory tests, biopsies and endoscopy procedures, which delay treatment. To improve diagnosis for patients with complex metastatic cancers, especially those in low-resource settings, researchers from the Mahmood Lab at the Brigham and Women's Hospital developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system that uses routinely acquired histology slides to accurately find the origins of metastatic ...

2021-05-05

The Antarctic ice sheet is much less likely to become unstable and cause dramatic sea-level rise in upcoming centuries if the world follows policies that keep global warming below a key END ...

2021-05-05

Mitochondria either split in half to multiply within the cell, or cut off their ends to get rid of damaged material. That's the take-away message from EPFL biophysicists in their latest research investigating mitochondrial fission. It's a major departure from the classical textbook explanation of the life cycle of this well-known organelle, the powerhouse of the cell. The results are published today in Nature.

"Until this study, it was poorly understood how mitochondria decide where and when to divide," says EPFL biophysicist Suliana Manley and senior author of the study.

The big question : regulating mitochondrial fission

Mitochondrial fission is important for the proliferation of mitochondria, which is fundamental for cellular growth. As a cell gets bigger, ...

2021-05-05

The discovery of the earliest human burial site yet found in Africa, by an international team including several CNRS researchers1, has just been announced in the journal Nature. At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, north of Mombasa, the body of a three-year-old, dubbed Mtoto (Swahili for 'child') by the researchers, was deposited and buried in an excavated pit approximately 78,000 years ago. Through analysis of sediments and the arrangement of the bones, the research team showed that the body had been protected by being wrapped in a shroud made of perishable material, and that the head had likely rested on an object also of perishable material. Though there are no signs of offerings or ochre, both common at more recent burial ...

2021-05-05

Among the upper echelons of academic surgery, Black and Latinx representation has remained flat over the past six years, according to a study published today in JAMA Surgery by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and University of Florida Health.

The study tracked trends across more than 15,000 faculty in surgery departments across the U.S. between 2013-2019. Although the data revealed modest diversity gains among early-career faculty during this period, especially for Black and Latina women, the percentage of full professors and department chairs identifying as Black or Latinx continued to hover in the single digits. ...

2021-05-05

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- For all animals, eliminating some cells is a necessary part of embryonic development. Living cells are also naturally sloughed off in mature tissues; for example, the lining of the intestine turns over every few days.

One way that organisms get rid of unneeded cells is through a process called extrusion, which allows cells to be squeezed out of a layer of tissue without disrupting the layer of cells left behind. MIT biologists have now discovered that this process is triggered when cells are unable to replicate their DNA during cell division.

The researchers discovered this mechanism in the worm C. elegans, and they showed that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Cardiovascular disease could be diagnosed earlier with new glowing probe