The evolution of photosynthesis better documented thanks to the discovery of the oldest thylakoids in fossil cyanobacteria

This major discovery by researchers from the Early Life Traces & Evolution Laboratory at ULiège offers a new approach to decipher the early diversification of life and for clarifying the role of cyanobacteria in the Great Oxygenation of the Earth

2024-01-05

(Press-News.org)

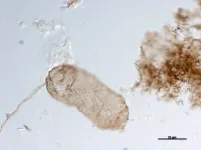

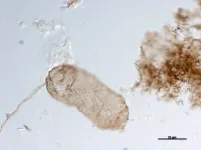

Researchers at the University of Liège (ULiège) have identified microstructures in fossil cells that are 1.75 billion years old. These structures, called thylakoid membranes, are the oldest ever discovered. They push back the fossil record of thylakoids by 1.2 billion years and provide new information on the evolution of cyanobacteria which played a crucial role in the accumulation of oxygen on the early Earth. This major discovery is presented in the journal Nature.

Catherine Demoulin, Yannick Lara, Alexandre Lambion and Emmanuelle Javaux from the Early Life Traces & Evolution laboratory of the Astrobiology Research Unit at ULiège examined enigmatic microfossils called Navifusa majensis (N.majensis) in shales from the McDermott Formation in Australia, which are 1.75 billion years old, and in 1 billion year old formations of DRCongo and arctic Canada. Ultrastructural analyses in fossil cells from 2 formations (Australia, Canada) revealed the presence of internal membranes with an arrangement, fine structure and dimensions permitting to interpret them unambiguously as thylakoid membranes, where oxygenic photosynthesis occurs. These observations permitted to identify N majensis as a fossil cyanobacterium.

This discovery puts into perspective the role of cyanobacteria with thylakoid membranes in early Earth oxygenation. They played an important role in the early evolution of life and were active during the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE), around 2.4 billion years ago. However, the chronology of the origins of oxygenic photosynthesis and the type of cyanobacteria (protocyanobacteria? With or without thylakoids?) involved remain debated, and the ULiège researchers' discovery offers a new approach to clarify these issues.

"The oldest known fossil thylakoids date back to around 550 million years. The ones we have identified therefore extend the fossil record by 1.2 billion years", explains Professor Emmanuelle Javaux, paleobiologist and astrobiologist, director of the Early Life Traces & Evolution laboratory at ULiège.

"The discovery of preserved thylakoids in N. majensis provides direct evidence of a minimum age of around 1.75 billion years for the divergence between cyanobacteria with thylakoids and those without."

But the ULiège team's discovery raises the possibility to discover thylakoids in even older cyanobacterial fossils, and to test the hypothesis that the emergence of thylakoids may have played a major role in the great oxygenation of the early Earth around 2.4 billion years ago. This approach also permits to examine the role of dioxygen in the evolution of complex life (eucaryote) on our planet, including the origin and early diversification of algae that host chloroplasts derived from cyanobacteria.

"Microscopic life is beautiful, the most diverse and abundant form of life on Earth since the origin of life. Studying its fossil record using new approaches will enable us to understand how life evolved over at least 3.5 billion years. Some of this research also tells us how to search for traces of life beyond Earth!", concludes Emmanuelle Javaux.

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-01-05

A new study in Advanced Science unlocks the secrets of how high blood pressure (hypertension) fuels the progression of arterial disease. Led by Professor Thomas Iskratsch, Professor of Cardiovascular Mechanobiology & Bioengineering at Queen Mary University of London, the research team exposes a novel mechanism by which elevated pressure transforms muscle cells in the arterial wall into "foam cells" – the building blocks of plaque buildup that cripples arteries.

The study focuses on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), the workhorses responsible for maintaining blood vessel tone and flow. Under ...

2024-01-05

WASHINGTON – U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) researchers, Kevin Cronin and Drew Rodgers, receive Technology Achievement Award for Lightweight Hydrogen Fuel Cells for Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) research efforts at Defense Manufacturing Conference held in Nashville, Tenn., Dec. 11, 2023.

The Department of Defense (DOD) has a critical need for increased power and endurance for persistent Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and transmission of radio frequency (RF) sources for communications and targeting.

“It ...

2024-01-05

The São Paulo Advanced School on Technology & Innovation Strategies and Policies for Economic Development will be held from June 24 to July 05, 2024, at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in São Paulo state, Brazil.

Reporters are invited to register for the scientific sessions and short courses, which will present state-of-art science and results of new research.

The School provides an opportunity to learn about and debate recent developments in the economics of technological change and in science, technology and innovation (ST&I) policy studies. The programme comprises numerous seminars, intensive courses, and roundtable discussions focusing ...

2024-01-05

A study carried out by CNRS1 scientists working with an international team has revealed that around 70 million years ago, when dinosaurs existed, the ancestors of primates most commonly lived in pairs. Only 15% of them opted for a solitary lifestyle. This discovery — that our ancestors adopted variable forms of social organization — challenges the hitherto commonly accepted hypothesis that at the time of dinosaurs, the ancestors of primates lived alone, and that pair living evolved much later. Most likely, pair living offered significant benefits, such as easier reproduction and reduced costs of thermoregulation by huddling in pairs.

While several studies have already been conducted ...

2024-01-05

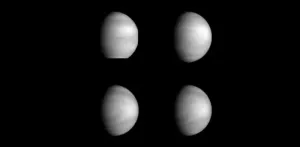

What are the clouds of Venus made of? Scientists know it’s mainly made of sulfuric acid droplets, with some water, chlorine, and iron. Their concentrations vary with height in the thick and hostile Venusian atmosphere. But until now they have been unable to identify the missing component that would explain the clouds’ patches and streaks, only visible in the UV range.

In a new study published in Science Advances, researchers from the University of Cambridge synthesised iron-bearing sulfate minerals that are stable under the harsh chemical conditions in the Venusian clouds. Spectroscopic analysis revealed that a combination of two minerals, rhomboclase and acid ferric ...

2024-01-05

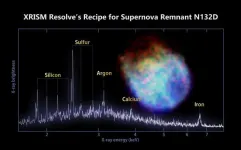

The Japan-led XRISM (X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) observatory has released a first look at the unprecedented data it will collect when science operations begin later this year.

The satellite’s science team released a snapshot of a cluster of hundreds of galaxies and a spectrum of stellar wreckage in a neighboring galaxy, which gives scientists a detailed look at its chemical makeup.

“XRISM will provide the international science community with a new glimpse of the hidden X-ray sky,” said Richard Kelley, the ...

2024-01-05

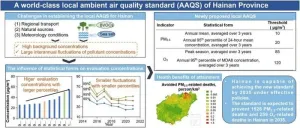

Air pollution significantly impacts human health, with Hainan Province in China aiming to achieve world-leading ambient air quality by 2035, despite already having relatively good air quality in China. The existing Ambient Air Quality Standards (AAQS) offer insufficient guidance for further enhancing air quality in Hainan, which stands at the forefront of China's environmental protection efforts. Consequently, it is imperative to develop Hainan's local AAQS. This initiative, responding to WHO's strengthened guidelines, aims to address unique regional challenges in air quality ...

2024-01-05

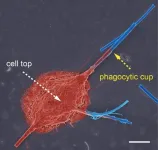

The pathogenic potential of inhaling the inert fibrous nanomaterials used in thermal insulation (such as asbestos or fibreglass) is actually connected not to their chemical composition, but instead to their geometrical characteristics and size. This was revealed by a study, published on 3 January 2024 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, conducted on glass nanofibers by a French-Chinese team including a CNRS chemist.1

The reason for this is the inability of the macrophages2 naturally present in pulmonary alveolar tissue to eliminate foreign bodies that are too large. The study was initially conducted in vitro with electrochemical nanosensors, and revealed that when confronted ...

2024-01-05

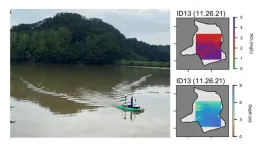

In a recent tragic incident, approximately 100 elephants in Africa perished due to inadequate access to water. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) issues a warning that around 2.5 billion people worldwide could face water scarcity by 2025. In the face of water shortages affecting not only human society but also the entire ecological community due to the climate crisis, it becomes crucial to adopt comprehensive measures for managing water quality and quantity to avert such pressing challenges.

A research team led by Professor Jonghun Kam and PhD candidate Kwang-Hun Lee from the Division of Environmental Science and ...

2024-01-05

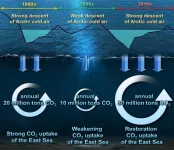

The recent cold spell has plunged the nation into a deep freeze, resulting in the closure of 247 national parks, the cancellation of 14 domestic flights, and the scrapping of 107 cruise ship voyages. While the cold snap brought relief by significantly reducing the prevalence of particulate matter obscuring our surroundings, a recent study indicates that, besides diminishing particulate matter, it is significantly contributing to the heightened uptake of carbon dioxide by the East Sea.

According to research conducted by a team of researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The evolution of photosynthesis better documented thanks to the discovery of the oldest thylakoids in fossil cyanobacteria

This major discovery by researchers from the Early Life Traces & Evolution Laboratory at ULiège offers a new approach to decipher the early diversification of life and for clarifying the role of cyanobacteria in the Great Oxygenation of the Earth