(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — UC Santa Barbara professors Andrew Jayich and Jon Schuller have been selected by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to be part of the 2024 cohort of Experimental Physics Investigators. They join 17 other mid-career researchers from around the country, each receiving a five-year, $1.25 million grant to pursue research goals.

“This initiative is designed to support novel and potentially high-payoff projects that will advance the field of physics but might be hard to fund through traditional funding sources,” said Theodore Hodapp, program director for the initiative. “Via an open call for proposals, we have lowered the barriers for researchers from a wide range of institutions and experiences to apply. We are delighted with the variety of ideas and projects this year’s cohort represents.”

“I congratulate Andrew Jayich and Jonathan Schuller on this impressive award from the Moore Foundation,” said Pierre Wiltzius, UCSB’s Susan and Bruce Worster Dean of Science. “This funding, which can be difficult to secure from traditional sources, will provide meaningful support as they investigate essential questions of what the nature of our physical world is.”

“The simplest way to boil down the question we’re trying to address is: Why is everything around us composed of matter?” said Jayich, a physics professor. During the time of the Big Bang almost 14 billion years ago, he explained, equal amounts of matter and antimatter were produced, which ought to have annihilated each other, leaving nothing behind except light. “But somehow there ended up being a bit more matter than antimatter,” he said, which constitutes our visible universe.

This imbalance implies a violation of a principle called time-reversal (T) symmetry or T-symmetry, which states that the rules of physics are the same regardless whether time is going forward or backward, Jayich said. According to T-symmetry, one can predict from a state of a system at one time the state of the system at another time. Had there been no T-symmetry violation, Jayich said, there would be nothing left over, just light. And the best theory of particle physics — the Standard Model — can’t explain the equal production of matter and antimatter particles at the very beginning of the universe to the remaining mass that exists.

“And so, the key is to look for new particles and interactions that break time reversal symmetry,” he said. “And we can do that by looking at an electron really carefully.”

The plan is to use defects in a solid — irregularities and imperfections in the otherwise uniform arrangement of atoms and molecules in a crystal — to study the electron, Jayich said. In particular, his research group will look for the electron’s permanent electric dipole moment (EDM), a distribution of the electron’s charge where the top is a bit more positive than the bottom, which could occur if particles appear nearby and interact with it.

“All the matter around us is continuously getting ‘dressed’ by particles,” Jayich explained. “They’re popping in and out of the vacuum. So, we can use that to tease out the presence of these new particles.” Using the solid-state approach would allow for many atomic defects in the crystal to search for the electron EDM, leading to great sensitivity; and the experiment is relatively simple, so it would take less effort to hold the system together.

If the team finds an electron EDM, it could indicate the presence of new fundamental particles that could help explain the matter-antimatter symmetry problem. But, even if they don’t detect new particles, a more precise measurement will allow for a better grip on one of physics’ biggest mysteries.

“This field of EDM searches can help guide theoretical physicists working on new theories to explain mysteries such as the matter-antimatter asymmetry,” he said. “The Moore EPI award will allow the group to pursue this exciting new research direction.”

“On behalf of the College of Engineering, we congratulate Professor Schuller and Professor Jayich on being named Moore Investigators,” said Umesh Mishra, dean of the College of Engineering. “We are thrilled that the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation has recognized the potential transformative impact of these two researchers and their leading-edge work on fundamental aspects of matter.”

Schuller’s work focuses on interactions between light and matter. Specifically, when light hits a material, there are different possibilities for interaction, depending on the properties of both the material and the light. Some of the most readily observed tend to be in the realm of linear interactions, such as reflection and diffraction.

“A linear light-matter interaction basically means it’s an interaction that involves only one photon at a time,” said Schuller, a professor in UCSB’s Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) Department. “So you absorb one photon or you emit one photon.” Nonlinear light-matter interactions, meanwhile, result in changes to the properties of the light after it interacts with the material. It may change in intensity, perhaps, or color, and may involve two or more photons at a time. These interactions are often driven in applications such as imaging, telecommunications and photonics.

In addition, Schuller explained, although light is an electromagnetic wave, with both electric and magnetic fields, light-matter interactions are generally assumed to be driven solely by the electric field, leaving the magnetic field untouched. “We treat materials within what’s called the electric dipole approximation,”, a method for predicting how light would interact with the atoms or molecules of the material.

Recently, however, Schuller’s lab has tapped into the magnetic component.

“We recently discovered a very unusual, truly unique magnetic dipole mediated light-matter interaction,” he said. “This is where the magnetic field component of light is being absorbed, or in the time-reverse process, emitting light through these magnetic dipoles.” Using a material structure called a perovskite, they were able to coax unprecedented interactions with the magnetic field.

So far, what they have demonstrated with the magnetic dipole mediated interactions fall into the realm of linear interactions — photon in, photon out. But what Schuller is interested in is exploring the nonlinear interaction realm.

“We’re trying to discover, based on what we’ve seen before, new types of nonlinear interactions that are driven by the magnetic field,” he said, adding that there’s as much energy in the magnetic field as there is in the electric field.

Part of what makes this work particularly enticing for Schuller is that the interaction they discovered is forbidden by symmetry. The distortion of the light when it interacts with the material breaks that symmetry, he explained, which is why they were able to see it. Which begs the question: Are there other material classes where these “forbidden” interactions might also be possible?

To investigate this and other questions, Schuller and his team will be developing a specialized spectroscopy apparatus to control and measure the energy and momentum of the photons that interact with the material as well as the ones that are generated due to the interaction. This instrument will also allow them to investigate magnetic field nonlinearities, and peer into other materials that may harbor this new class of interactions.

The impact of this work could be tremendous, from a new fundamental understanding of light-matter interactions with the relatively unexplored magnetic field, to applications that use findings from this work to create new optics material systems and technologies.

“I'm very grateful to the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for their generous support, which comes at a very pivotal stage of my career,” Schuller said. “The duration and level of support greatly surpass what is available from conventional funding sources, allowing my group to tackle exciting new research explorations.”

END

Two UCSB professors selected by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to be Experimental Physics Investigators

2024-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study of pythons could lead to new therapies for heart disease, other illnesses

2024-08-21

In the first 24 hours after a python devours its massive prey, its heart grows 25%, its cardiac tissue softens dramatically, and the organ squeezes harder and harder to more than double its pulse. Meanwhile, a vast collection of specialized genes kicks into action to help boost the snake’s metabolism fortyfold. Two weeks later, after its feast has been digested, all systems return to normal—its heart remaining just slightly larger, and even stronger, than before.

This extraordinary process, described by CU Boulder researchers this week in the journal PNAS, could ultimately inspire novel treatments for a common human heart condition called cardiac fibrosis, in which ...

Study finds no link between migraine and Parkinson’s disease

2024-08-21

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL 4 P.M. ET, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 21, 2024

MINNEAPOLIS – Contrary to previous research, a new study of female participants finds no link between migraine and the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The study is published in the August 21, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“These results are reassuring for women who have migraine, which itself causes many burdens, that they don’t have to worry about an increased risk ...

How personality traits might interact to affect self-control

2024-08-21

Neuroticism may moderate the relationship between certain personality traits and self-control, and the interaction effects appear to differ by the type of self-control, according to a study published August 21, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Fredrik Nilsen from the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Defence University, Norway, and colleagues.

Self-control is important for mental and physical health, and certain personality traits are linked to the trait. Previous studies suggest that conscientiousness and extraversion enhance self-control, whereas neuroticism hampers it. However, the link between personality ...

US Congress members’ wealth statistically linked with ancestors’ slaveholding practices

2024-08-21

Per a new study, as of April 2021, US Congress members whose ancestors enslaved 16 or more people had a net worth that was five times higher than that of legislators whose ancestors did not have slaves. Neil Sehgal of the University of Pennsylvania, US, and Ashwini Sehgal of Case Western Reserve University, US present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on August 21, 2024.

Prior research has linked slavery’s intergenerational effects to contemporary inequality, poverty, education, voting behavior, and life expectancy in the US However, the extent to which past slavery in the US contributes to today’s social and economic conditions remains ...

Following a Mediterranean diet may be associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 infection, per systematic review

2024-08-21

Following a Mediterranean diet may be associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 infection, per systematic review, although it's unclear if the diet is also associated with reduced symptoms and severity of illness.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0301564

Article Title: Relevance of Mediterranean diet as a nutritional strategy in diminishing COVID-19 risk: A systematic review

Author Countries: Indonesia

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. END ...

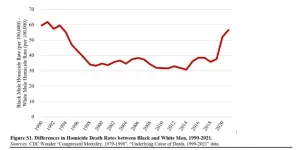

Homicide rates are a major factor in the gap between Black and White life expectancy

2024-08-21

Homicide is a major reason behind lower and more variable reduction in life expectancy for Black rather than White men in recent years, according to a new study published August 21, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Michael Light and Karl Vachuska of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a staggering drop in U.S. life expectancy and substantially widened Black-White disparities in lifespan. It also coincided with the largest one-year increase in the U.S. homicide rate in more than a century, with Black men bearing the brunt of these. Despite these trends, there has been limited research on the contribution ...

Human-wildlife overlap expected to increase across more than half of land on Earth by 2070

2024-08-21

ANN ARBOR—As the human population grows, more than half of Earth's land will experience an increasing overlap between humans and animals by 2070, according to a University of Michigan study.

Greater human-wildlife overlap could lead to more conflict between people and animals, say the U-M researchers. But understanding where the overlap is likely to occur—and which animals are likely to interact with humans in specific areas—will be crucial information for urban planners, conservationists and countries that have pledged international conservation commitments. Their findings ...

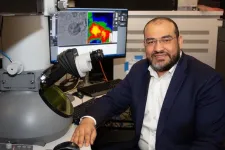

Freeze-frame: U of A researchers develop world's fastest microscope that can see electrons in motion

2024-08-21

Imagine owning a camera so powerful it can take freeze-frame photographs of a moving electron – an object traveling so fast it could circle the Earth many times in a matter of a second. Researchers at the University of Arizona have developed the world's fastest electron microscope that can do just that.

They believe their work will lead to groundbreaking advancements in physics, chemistry, bioengineering, materials sciences and more.

"When you get the latest version of a smartphone, it comes with a better camera," said Mohammed Hassan, associate professor of physics and optical sciences. "This transmission electron microscope is ...

Study finds highest prediction of sea-level rise unlikely

2024-08-21

In recent years, the news about Earth's climate—from raging wildfires and stronger hurricanes, to devastating floods and searing heat waves—has provided little good news.

A new Dartmouth-led study, however, reports that one of the very worst projections of how high the world's oceans might rise as the planet's polar ice sheets melt is highly unlikely—though it stresses that the accelerating loss of ice from Greenland and Antarctica is nonetheless dire.

The study challenges a new and alarming prediction in the latest high-profile report from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on ...

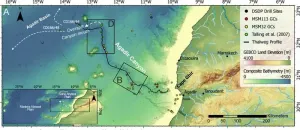

New study reveals devastating power and colossal extent of a giant underwater avalanche off the Moroccan coast

2024-08-21

New research by the University of Liverpool has revealed how an underwater avalanche grew more than 100 times in size causing a huge trail of destruction as it travelled 2000km across the Atlantic Ocean seafloor off the North West coast of Africa.

In a study publishing in the journal Science Advances (and featured on the front cover), researchers provide an unprecedented insight into the scale, force and impact of one of nature’s mysterious phenomena, underwater avalanches.

Dr Chris Stevenson, a sedimentologist from the University of Liverpool’s School of Environmental Sciences, co-led the team that for the first time has mapped a giant underwater avalanche from head ...