(Press-News.org) The interplay between an infection during pregnancy and stress in puberty plays a key role in the development of schizophrenia, as behaviourists from ETH Zurich demonstrate in a mouse model. However, there is no need to panic.

Around one per cent of the population suffers from schizophrenia, a serious mental disorder that usually does not develop until adulthood and is incurable. Psychiatrists and neuroscientsist have long suspected that adverse enviromental factors may play an important role in the development of schizophrenia. Prenatal infections such as toxoplasmosis or influenza, psychological, stress or family history have all come into question as risk factors. Nevertheless, until now researchers were unable to identify the interplay of the individual factors linked to this serious mental disease.

However, a research group headed by Urs Meyer, a senior scientist at the Laboratory of Physiology & Behaviour at ETH Zurich, has now made a breakthrough: for the first time, they were able to find clear evidence that the combination of two environmental factors contributes significantly to the development of schizophrenia-relevant brain changes and at which stages in a person's life they need to come into play for the disorder to break out. The researchers developed a special mouse model, with which they were able to simulate the processes in humans virtually in fast forward. The study has just been published in the journal Science.

Interplay between infection and stress

The first negative environmental influence that favours schizophrenia is a viral infection of the mother during the first half of the pregnancy. If a child with such a prenatal infectious history is also exposed to major stress during puberty, the probability that he or she will suffer from schizophrenia later increases markedly. Hence, the mental disorder needs the combination of these two negative environmental influences to develop. "Only one of the factors – namely an infection or stress – is not enough to develop schizophrenia," underscores Meyer.

The infection during pregnancy lays the foundation for stress to "take hold" in puberty. After all, the mother's infection activates certain immune cells of the central nervous system in the brain of the foetus: microglial cells, which produce cytotoxins that alter the brain development of the unborn child.

Mouse model provides important clue

Once the mother's infection subsides, the microglial cells lie dormant but have developed a "memory". If the adolescent suffers severe, chronic stress during puberty, such as sexual abuse or physical violence, the microglial cells awake and induce changes in certain brain regions through this adverse postnatal stimulus. Ultimately, these neuroimmunological changes do not have a devastating impact until adulthood. The brain seems to react particularly sensitively to negative influences in puberty as this is the period during which it matures. "Evidently, something goes wrong with the 'hardware' that can no longer be healed," says Sandra Giovanoli, who, as a doctoral student under Urs Meyer, did the lion's share of the work on this study.

The researchers achieved their ground-breaking results based on sophisticated mouse models, using a special substance to trigger an infection in pregnant mouse mothers to provoke an immune response. Thirty to forty days after birth – the age at which the animals become sexually mature, which is the equivalent of puberty – the young animals were exposed to five different stressors which the mice were not expecting. This stress is the equivalent of chronic psychological stress in humans.

Diminished filter function

Afterwards, the researchers tested the animals' behaviour directly after puberty and in adulthood,. As a control, the scientists also studied mice with either an infection or stress, as well as animals that were not exposed to either of the two risk factors.

When the researchers examined the behaviour of the animals directly after puberty, they were not able to detect any abnormalities. In adulthood, however, the mice that had both the infection and stress behaved abnormally. The behaviour patterns observed in the animals are comparable to those of schizophrenic humans. For instance, the rodents were less receptive to auditory stimuli, which went hand in hand with a diminished filter function in the brain. The mice also responded far more strongly to psychoactive substances such as amphetamine.

Environmental influences more significant again

"Our result is extremely relevant for human epidemiology," says Meyer. Even more importance will be attached to environmental influences again in the consideration of human disorders – especially in neuropsychology. "It isn't all genetics after all," he says.

Although certain symptoms of schizophrenia can be treated with medication, the disease is not curable. However, the study provides hope that we will at least be able to take preventative action against the disorder in high-risk people. The study is a key foundation upon which other branches of research can build.

The ETH Zurich researchers also stress that the results of their work are no reason for pregnant women to panic. Many expecting mothers get infections such as herpes, a cold or the flu. And every child goes through stress during puberty, whether it be through bullying at school or quarrelling at home. "A lot has to come together in the 'right' time window for the probability of developing schizophrenia to be high," says Giovanoli. Ultimately, other factors are also involved in the progress of the disease. Genetics, for instance, which was not taken into consideration in the study, can also play a role. But unlike genes, certain environmental influences can be changed, adds the doctoral student; how one responds to and copes with stress is learnable.

### END

New Rochelle, NY, March 1, 2013—Most adults and children with type 1 diabetes are not in optimal glycemic control, despite advances in insulin formulations and delivery systems and glucose monitoring approaches. Critical barriers to optimal glycemic control remain. A panel of experts in diabetes management and research met to explore these challenges, and their conclusions and recommendations for how to improve care and optimize clinical decision-making are presented in a white paper in Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics (DTT), a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, ...

(Boston) – A study led by researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) has identified epigenetic mechanisms that connect a variety of diseases associated with inflammation. Utilizing molecular analyses of gene expression in macrophages, which are cells largely responsible for inflammation, researchers have shown that inhibiting a defined group of proteins could help decrease the inflammatory response associated with diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and sepsis.

The study, which is published online in the Journal of Immunology, was led by ...

SEATTLE – A study of older patients with advanced head and neck cancers has found that where they were treated significantly influenced their survival.

The study, led by researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and published in the March 1 online edition of Cancer, found that patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a high number of head and neck cancers were 15 percent less likely to die of their disease as compared to patients who were treated at hospitals that saw a relatively low number of such cancers. The study also found that such patients ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A study published in the journal Science reveals a decline in bee species since the late 1800s in West Central Illinois. The study could not have been conducted without the work of a 19th-century naturalist, says a co-author of the new research.

Charles Robertson, a self-taught entomologist who studied zoology and botany at Harvard University and the University of Illinois, was one of the first scientists to make detailed records of the interactions of wild bees and the plants they pollinate, says John Marlin, a co-author of the new analysis in Science. ...

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – In an article published as the cover story of the March 2013 issue of Nature Chemical Biology, Lindsey James, PhD, research assistant professor in the lab of Stephen Frye, Fred Eshelman Distinguished Professor in the UNC School of Pharmacy and member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, announced the discovery of a chemical probe that can be used to investigate the L3MBTL3 methyl-lysine reader domain. The probe, named UNC1215, will provide researchers with a powerful tool to investigate the function of malignant brain tumor (MBT) domain ...

Colon cancer develops slowly. Precancerous lesions usually need many years to turn into a dangerous carcinoma. They are well detectable in an endoscopic examination of the colon called colonoscopy and can be removed during the same examination. Therefore, regular screening can prevent colon cancer much better than other types of cancer. Since 2002, colonoscopy is part of the national statutory cancer screening program in Germany for all insured persons aged 55 or older.

However, only one fifth of those eligible actually make use of the screening program. The reasons ...

This press release is available in French.

Montreal, March 1, 2013 – Construction in Montreal is under a microscope. Now more than ever, municipal builders need to comply with long-term urban planning goals. The difficulties surrounding massive projects like the Turcot interchange lead Montrealers to wonder if construction in this city is headed in the right direction. New research from Concordia University gives us hope that this could soon be the case if sufficient effort is made.

A team of graduate students from Concordia's Department of Geography, Planning and Environment ...

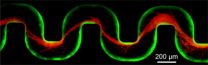

A new study has examined how bacteria clog medical devices, and the result isn't pretty. The microbes join to create slimy ribbons that tangle and trap other passing bacteria, creating a full blockage in a startlingly short period of time.

The finding could help shape strategies for preventing clogging of devices such as stents — which are implanted in the body to keep open blood vessels and passages — as well as water filters and other items that are susceptible to contamination. The research was published in Proceedings of the National ...

The bacteria that cause acne live on everyone's skin, yet one in five people is lucky enough to develop only an occasional pimple over a lifetime.

In a boon for teenagers everywhere, a UCLA study conducted with researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute has discovered that acne bacteria contain "bad" strains associated with pimples and "good" strains that may protect the skin.

The findings, published in the Feb. 28 edition of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, could lead to a myriad of new therapies to ...

Ecologists have evidence that some endangered primates and large cats faced with relentless human encroachment will seek sanctuary in the sultry thickets of mangrove and peat swamp forests. These harsh coastal biomes are characterized by thick vegetation — particularly clusters of salt-loving mangrove trees — and poor soil in the form of highly acidic peat, which is the waterlogged remains of partially decomposed leaves and wood. As such, swamp forests are among the few areas in many African and Asian countries that humans are relatively less interested in exploiting (though ...