(Press-News.org) Bark beetle outbreaks and wildfire alone are not a death sentence for Colorado's beloved forests--but when combined, their toll may become more permanent, shows new research from the University of Colorado Boulder.

It finds that when wildfire follows a severe spruce beetle outbreak in the Rocky Mountains, Engelmann spruce trees are unable to recover and grow back, while aspen tree roots survive underground. The study, published last month in Ecosphere, is one of the first to document the effects of bark beetle kill on high elevation forests' recovery from wildfire.

"The fact that Aspen is regenerating prolifically after wildfire is not a surprise," said Robert Andrus, who conducted this research while working on his PhD in physical geography at CU Boulder. "The surprising piece here is that after beetle kill and then wildfire, there aren't really any spruce regenerating."

Andrus' previous research found that bark beetle outbreaks are not a death sentence to Colorado forests--even after overlapping outbreaks with different kinds of beetles--and that spruce bark beetle infestations do not affect fire severity.

This new research, conducted in the San Juan range of the Rocky Mountains, shows that subalpine forests that have not been attacked by bark beetles will likely recover after wildfire. But for forests that suffer from a severe bark beetle outbreak followed by wildfire within about five years, conifers cannot mount a comeback. While these subalpine forests can often take a century to recover from fire, this research on short-term recovery is a good predictor of longer-term trends.

"This combination, the spruce beetle outbreak and the fire, can alter the trajectory of the forest to dominance by aspen," said Andrus, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Washington State University.

For those worried about the future of Rocky Mountain forests farther north, more research is needed on areas burned in the 2020 East Troublesome Fire to understand how the mountain pine beetle outbreak prior to that fire will affect forest recovery, according to Andrus.

The next generation

Each bark beetle species specializes in attacking--and usually killing--a specific host tree species or closely related species. Several species of bark beetle are native to Colorado and usually exist at low abundances, killing only dying or weakened trees. But as the climate becomes hotter and drier, their populations can explode, causing outbreaks which kill large numbers of even the healthiest trees.

These large, healthy Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir trees are the ones that produce the most seeds. When bark beetles kill these trees and then fire sweeps in, the researchers found there simply aren't enough seeds being produced in the burned areas to regenerate the forest.

Aspens, however, regrow from their root systems. While all three of these higher elevation trees have thin bark and die when exposed to fire, with their regenerative roots underground, aspens can bounce back where conifers cannot.

The researchers focused specifically on areas of forest affected by spruce bark beetle outbreaks, which attack Engelmann spruce, where fires such as Papoose, West Fork and Little Sands burned in 2012 and 2013 in Rio Grande National Forest. They found that for forests that suffer from a severe bark beetle outbreak followed by wildfire within about five years, Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir trees failed to recover in 74% of the 45 sites sampled.

This information will help inform land managers and policy makers about the implications for high elevation forest recovery following a combination of stressors and events.

And it's more important information than ever. Not only do bark beetle outbreaks leave behind swaths of dead, dry trees--and fewer trees to produce seeds--but the climate is getting hotter and droughts are becoming more frequent, promoting larger fires.

"Bark beetle outbreaks have been killing lots and lots of trees throughout the western United States. And especially at higher elevation forests, what drives bark beetle outbreaks and what drives fire are similar conditions: generally warmer and drier conditions," said Andrus.

But there is good news: The aspens that may come to dominate these forests can anchor their recovery, and keep forests from transitioning into grasslands.

"Where the aspen are regenerating, we expect to see a forest in those areas," said Andrus.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on this publication include Thomas Veblen at CU Boulder; and Sarah Hart and Niko Tutland of Colorado State University.

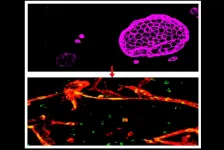

A team of engineers and scientists has developed a method of 'multiplying' organoids: miniature collections of cells that mimic the behaviour of various organs and are promising tools for the study of human biology and disease.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, used their method to culture and grow a 'mini-airway', the first time that a tube-shaped organoid has been developed without the need for any external support.

Using a mould made of a specialised polymer, the researchers were able to guide the size and shape of the mini-airway, grown from adult mouse stem cells, and then remove it from the mould when it reached ...

DANVILLE, Pa. - Researchers at Geisinger have found that a computer algorithm developed using echocardiogram videos of the heart can predict mortality within a year.

The algorithm--an example of what is known as machine learning, or artificial intelligence (AI)--outperformed other clinically used predictors, including pooled cohort equations and the Seattle Heart Failure score. The results of the study were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

"We were excited to find that machine learning can leverage unstructured datasets such as medical images and videos to improve on a wide range of clinical prediction models," said Chris Haggerty, Ph.D., co-senior author and assistant ...

A type of cell derived from human stem cells that has been widely used for brain research and drug development may have been leading researchers astray for years, according to a study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The cell, known as an induced Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (iBMEC), was first described by other researchers in 2012, and has been used to model the special lining of capillaries in the brain that is called the "blood-brain barrier." Many brain diseases, including brain cancers as well as degenerative ...

Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA ...

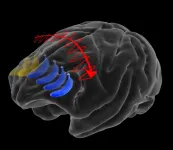

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

What The Study Did: This observational study compared different measures of prediabetes and the risk of progression to diabetes among adults age 71 to 90.

Authors: Mary R. Rooney, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed what percentage of the Virginia population had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 after the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the U.S.

Authors: Eric R. Houpt, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35234)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for ...