(Press-News.org) In 1913 in Southern California, two 241-mile-long electric lines began carrying power from hydroelectric dams in the Sierra Nevada to customers in Los Angeles--a massive feat of infrastructure. In 1923, power company Southern California Edison upgraded the line to carry 220,000 volts, among the highest voltage lines in the world at the time.

Then the problems started. Power interruptions caused by short circuits cropped up every few days, inconveniencing consumers and threatening to damage expensive equipment.

In a new paper in the journal Environmental Humanities, the University of Pennsylvania's Etienne Benson examines the suspected cause of the troubles: voluminous streams of bird excrement.

Benson is an assistant professor in the Department of History and Sociology of Science in Penn's School of Arts and Sciences. His piece considers the story of how the birds were identified as the likely culprit, the steps the power company took to ameliorate it, and how those interventions are rendered "invisible" to the end user, consumers who use electricity without full awareness of what is entailed in its generation.

"When you flip on a light switch you're not only engaging with a whole electrical system, but you're also engaging with the environment behind it," Benson said. "That part is rendered invisible. Most people don't think about the fact that when you turn on a light you're plugging into a system that involves hydroelectric dams, that almost certainly involves carbon dioxide emissions, and that may involve birds and other animals as well."

Benson, who has long been interested in human-animal relationships and how they're affected by technological developments, learned of the California electrical system and nature's role in affecting it through an article written in 1928 by engineer and amateur ornithologist Harold Michener.

Michener's article described several theories as to why Southern California Edison's power lines experienced short circuits. Company engineers proposed various causes--from lightning storms to spider webs--but none fully explained the problem. Finally, a worker observed what appeared to be an eagle perched on top of a transmission tower. As it launched itself from the tower into flight, a stream of semi-liquid droppings fell onto the power lines.

"They had a brain flash that it's actually the birds' excrement that causes it. They did lab tests and found it was possible," Benson said.

Benson corroborated the serious nature of this threat to the power grid through research into contemporaneous trade publications and the power company's own papers. The engineers' hypothesis was that hawks and eagles were attracted to the transmission towers as high lookout points from which to hunt. The jets of excrement they released when launching from the towers could carry electric current from the wire to the steel tower, causing a short circuit.

In response, the company installed barriers, spikes and excrement-catching pans on the towers--at considerable cost. The problem soon dissipated although it never vanished completely. In addition, as the power grid became more sophisticated, it was segmented and automatic relays were installed so that power could be more easily restored.

Benson termed these two strategies of reducing the effects of nature on technology "insulation," putting distance between the forces of nature and the infrastructure--and "interconnection," building resilience into the system. Both types of interventions, he noted, were invisible to consumers, who could simply access electricity without considering the hard work and environmental impact behind the generation of power.

His work engages with that of Thomas Hughes, a historian of technology and emeritus professor at Penn until his death last year. Hughes pushed forward the idea of considering the influence of whole systems rather than individual technologies. For electrical power systems, Benson explained, that systems thinking would suggest that their success "depended both on technical achievement and on the heterogeneous engineering of society, culture, politics and economics."

To this, Benson adds the natural environment and non-human actors as crucial influences that impact the operation and maintenance of infrastructure systems. And examples go far beyond just birds on transmission towers.

"It may not be birds," Benson said. "It could be squirrels, it could be ice or storms, but there are all these forces trying to rip things down. You could look at problems that homeowners have with sewer systems and plumbing where tree roots can break in and cause problems, or how the roads in Philadelphia are vulnerable to being broken apart by the environment."

To counteract and sometimes prevent these impacts, societies have implemented a variety of regimes of maintenance and protection to ensure that infrastructure continues to function, Benson said. Such interventions are ever-present in today's modern industrial landscape, even as people may go about their days without conscious awareness of them.

"We may think we're separate from nature, but actually everything we do is deeply embedded in it," Benson said. "The modern industrial landscape, which seems so hard and durable, requires constant maintenance for it to continue seeming hard and durable."

INFORMATION:

At its annual assembly in Geneva last week, the World Health Organization approved a radical and far-reaching plan to slow the rapid, extensive spread of antibiotic resistance around the world. The plan hopes to curb the rise caused by an unchecked use of antibiotics and lack of new antibiotics on the market.

New Tel Aviv University research published in PNAS introduces a promising new tool: a two-pronged system to combat this dangerous situation. It nukes antibiotic resistance in selected bacteria, and renders other bacteria more sensitive to antibiotics. The research, ...

La Jolla, Calif., June 4 -- In a scientific discovery that has significant implications for preventing HIV infections, researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) have identified a protein that could improve the body's immune response to HIV vaccines and prevent transmission of the virus.

The study shows how a protein called polyglutamine-binding protein 1 (PQBP1) acts as a front-line sensor and is critical to initiating an immune response to HIV. When the PQBP1 encounters the virus, it starts a program that triggers an overall protective ...

ANN ARBOR--African-American women are equally, if not more, likely to experience infertility than their white counterparts, but they often cope with this traumatic issue in silence and isolation, according to a new University of Michigan study.

African-American women also more often feel that infertility hinders their sense of self and gender identity.

The U-M study may be among the first known to focus exclusively on African-American women and infertility. Most research has been conducted on affluent white couples seeking advanced medical interventions.

"Infertile ...

ATLANTA--The ability to delay gratification in chimpanzees is linked to how specific structures of the brain are connected and communicate with each other, according to researchers at Georgia State University and Kennesaw State University.

Their findings were published June 3 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

This study provides the first evidence in primates, including humans, of an association between delay of gratification performance and white matter connectivity between the caudate and the dorsal prefrontal cortex in the right hemisphere, ...

A tougher federal standard for ozone pollution, under consideration to improve public health, would ramp up the importance of scientific measurements and models, according to a new commentary published in the June 5 edition of Science by researchers at NOAA and its cooperative institute at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The commentary, led by Owen Cooper of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences and NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory, looks at how a new, stricter ozone standard would pose challenges for air quality managers at state ...

Modern mountain climbers typically carry tanks of oxygen to help them reach the summit. It's the combination of physical exertion and lack of oxygen at high altitudes that creates one of the biggest challenges for mountaineers.

University of Washington researchers and collaborators have found that the same principle will apply to marine species under global warming. The warmer water temperatures will speed up the animals' metabolic need for oxygen, as also happens during exercise, but the warmer water will hold less of the oxygen needed to fuel their bodies, similar to ...

If you want to live, you need to breathe and muster enough energy to move, find nourishment and reproduce. This basic tenet is just as valid for us human beings as it is for the animals inhabiting our oceans. Unfortunately, most marine animals will find it harder to satisfy these criteria, which are vital to their survival, in the future. That was the key message of a new study recently published in the journal Science, in which American and German biologists defined the first universal principle on the combined effects of ocean warming and oxygen loss on the productivity ...

From a single drop of blood, researchers can now simultaneously test for more than 1,000 different strains of viruses that currently or have previously infected a person. Using a new method known as VirScan, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Harvard Medical School tested for evidence of past viral infections, detecting on average 10 viral species per person. The new work sheds light on the interplay between a person's immunity and the human virome -- the vast array of viruses that can infect humans - with implications both for the clinic and for the ...

PHILADELPHIA - Around-the-clock rhythms guide nearly all physiological processes in animals and plants. Each cell in the body contains special proteins that act on one another in interlocking feedback loops to generate near-24 hour oscillations called circadian rhythms. These dictate behaviors controlled by the brain, such as sleeping and eating, as well as metabolic, hormonal, and other rhythms that are intrinsic to the organs of the body. For example, when you eat may have affects on rhythms controlling fat or sugar metabolism, illustrating how circadian and metabolic ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

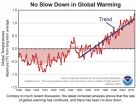

An analysis using updated global surface temperature data disputes the existence of a 21st century global warming slowdown described in studies including the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment. The new analysis suggests no discernable decrease in the rate of warming between the second half of the 20th century, a period marked by manmade warming, and the first fifteen years of the 21st century, a period dubbed a global warming "hiatus." Numerous studies have been done to explain the possible ...