Chlamydial infection ignites chronic inflammation, which scars mucosal surfaces such as eyelids, ovaries or fallopian tubes. Most people who carry the bacterium don't know it. Women with chlamydia are much more vulnerable to other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

The need for a vaccine against chlamydia has always been clear, but no vaccine trials have been mounted since the 1960s, when attempts to protect people against infection by immunization with killed chlamydia paradoxically made some of them even more vulnerable.

Now Harvard Medical School scientists report success in animals against this daunting public health challenge.

Generating two waves of protection

Working in a mouse model that mimics human chlamydial infection, they have deciphered what may have gone wrong 50 years ago. As a result, the researchers have created a vaccine that generates the two waves of protective immune cells needed to eliminate chlamydial infection. Their report appears in Science.

"This is really a very surprising and exciting observation," said Ulrich von Andrian, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Professor of Immunopathology at HMS and senior author of the paper. "We used this vaccine to try to really understand an immune response that was previously not that well worked out. Now our vaccine gives very good protection, even against different chlamydia strains."

The study represents collaboration with many scientific partners who are co-authors of the Science paper, notably Michael Starnbach, HMS professor of microbiology and immunology, Robert Langer, David H. Koch Institute Professor of biological engineering at MIT, and Omid Farokhzad, HMS associate professor of anaesthesia at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Delivery and packaging of the vaccine turned out to be key factors in their feat, based on insights they gained into why simply injecting an inactivated form of chlamydia backfired.

All vaccines carry antigen--pieces of the pathogen--usually combined with an adjuvant, and most of these antigen-adjuvant mixtures are injected into the skin or muscles.

The route of administration matters.

Schooling T cells

The vaccine passes through the lymph drainage system to local lymph nodes, which act as the "schoolhouse" of the immune system, teaching T cells to recognize and remember as a threat the antigen contained within the vaccine. The addition of an adjuvant to the antigens is intended to induce an immune response but not an infection.

T cells migrate from the blood into lymph nodes to receive regional information from the tissue that then discharges lymph to the lymph node. Certain lymph nodes collect, for example, antigens from bacteria that stuck on the piece of glass your toe finds on the beach, while other nodes associated with the gut sound the alarm if you drink spoiled milk. If a T cell becomes activated by an antigen, it will divide and differentiate into effector cells that travel to the source of the antigen, mount an inflammatory defense and eliminate the infectious agent.

Vaccines take advantage of the "memory" that these immune cells form after encountering antigens, but if the cells remember the skin or muscle where the vaccine is injected, they will poorly protect against a pathogen that infects other parts of the body, such as mucosal surfaces. In the case of chlamydia, that means the eye or mouth or female reproductive tract.

Giving vaccines through mucosal surfaces, such as those in the nose or under the tongue, could target memory cells to mucosal tissues, but this approach often hasn't worked well in the past. Vaccine antigens that are too weak to cause infection may also fail to elicit an immune response when applied to intact mucosa. Or, if they do manage to cause an immune response, it's the wrong kind: tolerance, meaning it tells immune cells not to fight off the infectious pathogen.

In the trials conducted in the 1960s, people received inactivated versions of chlamydia in vaccines injected through the skin or muscle. Later, some of these people became highly susceptible to exposure to chlamydia. The new study suggests that tolerance may have been the culprit.

Turbocharging immunization

One solution is to combine antigen with an adjuvant--a sort of turbocharger--that spells danger for the immune system. That helps, but adjuvants that work when injected through the skin are usually too weak for mucosal immunization. Worse, the more potent mucosal adjuvants themselves can be toxic.

von Andrian's team induced tolerance to killed chlamydia in mice and then asked how the killed chlamydia could be modified to ensure that the immune response generates protection instead of tolerance, without a harmful adjuvant. Their experiments showed that the vaccine and adjuvant must be tightly bound to each other to be sure they reach their target tissues together.

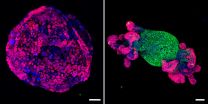

Enter charge-switching synthetic adjuvant nanoparticles, or cSAPs, which contain a powerful adjuvant in a tiny biodegradable sphere that binds to Chlamydia trachomatis, which naturally carries a negative surface charge. To form vaccine conjugates between cSAPs and inactivated chlamydia, the two vaccine components are mixed together in a buffer. cSAP binding to negatively charged chlamydia happens when the nanoparticles change their charge from negative to positive after addition of a mild acid to the buffer. This technology was developed in the labs of Farokhzad and Langer.

Acting locally

The conjugates are small enough to travel from a mucosal site--the nasal cavity, for example--to local lymph nodes where they are engulfed by antigen-presenting immune cells. The adjuvant within the nanoparticles becomes active only after uptake by the antigen-presenting cells, which then educate T cells to provide protection against Chlamydia in two waves.

"Mice that were given the cSAP vaccine very quickly eliminated Chlamydia and were even faster at completely clearing it than the animals that had developed natural immunity after a previous infection," von Andrian said.

Immunizing through the mucosa seems to stimulate T cells in such a way that two populations of memory cells arise. The first wave's members quickly migrate from the lymph nodes to the uterus and become tissue-resident memory cells and the second wave--which depends on the first wave to confer protection--are migratory memory cells that circulate in the blood.

Upon uterine infection, tissue-resident memory cells in vaccinated mice rapidly sensed the bacteria. Once activated, they rapidly instigated a local inflammatory response that stimulated the recruitment of the second wave of circulating memory cells. Together they cleared away the infection.

High stakes, low risk

The stakes are high, and not only because of the burden of disease from chlamydial infection. Because vaccines are given to healthy people, the risk must be low to gain acceptance.

"It will be very hard to convince anyone to try your vaccine unless you can explain why there might have been this paradoxical effect 50 years ago and why we are confident that this paradoxical effect will not be observed with the current formulation," von Andrian said. "I think we can provide reasonable answers to both of these questions." von Andrian called the study an example of multidisciplinary collaboration advancing biological understanding and the discovery of new paradigms for drug and vaccine development. In this case, the new cSAP technology was key to performing their research.

The idea of using pH-dependent charge-switching to conjugate nanocarriers to bacteria was recently developed by Aleksandar Radovic-Moreno, co-first author on the paper and a graduate student in Langer's lab who was co-supervised by Farokhzad. Both Farokhzad's and Langer's labs were critical in adapting this technology to engineer the cSAPs, which were used for the first time in the study's immunological experiments.

Similarly, Starnbach, whose lab has worked on chlamydia immunology for many years, provided tools, know-how and quantitative assays that were employed in the study.

The investigators are actively pursuing clinical translation of their new vaccine. To this end, Selecta Biosciences, a biotech company in the Boston area founded by Farokhzad, Langer and von Andrian, has licensed the cSAP technology. Selecta did not participate or contribute to the study, but it has licensed the intellectual property for this vaccine approach.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; a Harvard Innovation Award from Sanofi Pasteur; the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard; the David Koch Prostate Cancer Foundation; the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research; and the Epidemiology and Prevention Interdisciplinary Center for Sexually Transmitted Diseases.