Mixed and matched: Integrating metal-organic frameworks into polymers for CO2 separation

New strategy boosts the performance of membranes for filtering CO2 from industrial emissions

2021-02-08

(Press-News.org) One of humanity's biggest challenges right now is reducing our emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Research groups worldwide are trying to find ways to efficiently separate carbon dioxide (CO2) from the mixture of gases emitted from industrial plants and power stations. Among the many strategies for accomplishing this, membrane separation is an attractive, inexpensive option; it involves using polymer membranes that selectively filter CO2 from a mix of gases.

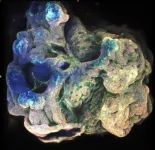

Recent studies have focused on adding low amounts of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) into polymer matrices to enhance their properties. MOFs are compounds made of a metallic center bonded to organic molecules in a very orderly fashion, producing porous crystals. When added to polymer membranes, MOFs can enhance their gas separation performance as well as their stability and tolerance to harsh conditions. However, one of the main issues of integrating MOFs into polymer membranes is finding compatible compounds with favorable interactions, such as covalent bonds. Unfortunately, those which have been tried require very expensive synthesis and materials.

To tackle this issue, an international team of scientists recently conducted a study that was published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. Led by Professor Tae-Hyun Kim from Incheon National University, Korea, the scientists focused on incorporating a zirconium-based MOF called 'UiO-66' into a multi-polymer matrix they had previously developed. They achieved this by modifying the MOFs so that they would readily form covalent bonds with the main strands of the polymer matrix.

The scientists synthesized UiO-66-NB, which is UiO-66 with norbornene units, a small organic molecule. Through a simple synthesis process, norbornene units can become links in the main polymer chains of the matrix. In this way, the norbornene in UiO-66-NB incorporates the MOFs into the matrix, as Prof. Kim explains, "Instead of simply blending the MOFs and polymers, we found a new and efficient method for incorporating MOFs into the polymer matrix via covalent bonds; this strengthens the interactions at the interfaces of both compounds and creates defect-free polymer matrices."

The characteristics and performance of the MOF-filled polymer membranes were outstanding: their permeability towards CO2 was enhanced without significantly compromising its selectivity. Their CO2/N2 separation performance approached the theoretical Robeson upper bound set in 2019. Additionally, the membranes were not only remarkably tolerant to harsh conditions such as high pressure or temperature switching, but also very stable over long periods of time of almost a year.

These achievements are a step in the right direction toward removing the barriers for commercialization that these polymer membranes face for industrial applications. Excited about the results, Prof. Kim remarks, "We believe our findings will open up new strategies to assess potential interfaces between MOFs and polymer matrices for high-performance gas separation."

Let us hope this technology keeps evolving so that we can keep excess CO2 away from our atmosphere!

INFORMATION:

Reference

Authors: Iqubal Hossain (1), Asmaul Husna (1), Somboon Chaemchuen (2), Francis Verpoort (3), and Tae-Hyun Kim (1)

Title of original paper: Cross-Linked Mixed-Matrix Membranes Using Functionalized UiO-66-NH2 into PEG/PPG?PDMS-Based Rubbery Polymer for Efficient CO2 Separation

Journal: ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces

DOI: 10.1021/acsami.0c18415

Affiliations:

(1) Organic Material Synthesis Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Incheon National University

(2) State Key Laboratory of Advanced Technology for Materials Synthesis and Processing, Wuhan University of Technology

(3) Department of Chemistry, Ghent University

About Incheon National University

Incheon National University (INU) is a comprehensive, student-focused university. It was founded in 1979 and given university status in 1988. One of the largest universities in South Korea, it houses nearly 14,000 students and 500 faculty members. In 2010, INU merged with Incheon City College to expand capacity and open more curricula. With its commitment to academic excellence and an unrelenting devotion to innovative research, INU offers its students real-world internship experiences. INU not only focuses on studying and learning but also strives to provide a supportive environment for students to follow their passion, grow, and, as their slogan says, be INspired.

Website: http://www.inu.ac.kr/mbshome/mbs/inuengl/index.html

About the author

Dr. Tae-Hyun Kim is a Chemistry Professor at Incheon National University (INU), Korea. He is also the director of the Research Institute of Basic Sciences at INU. Prof Kim received a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Cambridge University, UK and conducted his post-doctoral research at MIT, USA. Before joining INU, he was a senior research associate at Eastman Chemical Co., US. His research interests lie in the development of organic materials for various applications, including fuel cells, lithium batteries, water electrolysis, and gas separation. He has authored over 120 SCI journal articles and holds more than 50 patents. He loves teaching and communicating with his students.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- The world's most technologically advanced robots would lose in a competition with a tiny crustacean.

Just the size of a sunflower seed, the amphipod Dulichiella cf. appendiculata has been found by Duke researchers to snap its giant claw shut 10,000 times faster than the blink of a human eye.

The claw, which only occurs on one side in males, is impressive, reaching 30% of an adult's body mass. Its ultrafast closing makes an audible snap, creating water jets and sometimes producing small bubbles due to rapid changes in water pressure, a phenomenon known ...

2021-02-08

Bark beetle outbreaks and wildfire alone are not a death sentence for Colorado's beloved forests--but when combined, their toll may become more permanent, shows new research from the University of Colorado Boulder.

It finds that when wildfire follows a severe spruce beetle outbreak in the Rocky Mountains, Engelmann spruce trees are unable to recover and grow back, while aspen tree roots survive underground. The study, published last month in Ecosphere, is one of the first to document the effects of bark beetle kill on high elevation forests' recovery from wildfire.

"The fact that Aspen is regenerating prolifically after wildfire is not a surprise," said Robert Andrus, who conducted ...

2021-02-08

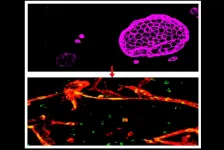

A team of engineers and scientists has developed a method of 'multiplying' organoids: miniature collections of cells that mimic the behaviour of various organs and are promising tools for the study of human biology and disease.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, used their method to culture and grow a 'mini-airway', the first time that a tube-shaped organoid has been developed without the need for any external support.

Using a mould made of a specialised polymer, the researchers were able to guide the size and shape of the mini-airway, grown from adult mouse stem cells, and then remove it from the mould when it reached ...

2021-02-08

DANVILLE, Pa. - Researchers at Geisinger have found that a computer algorithm developed using echocardiogram videos of the heart can predict mortality within a year.

The algorithm--an example of what is known as machine learning, or artificial intelligence (AI)--outperformed other clinically used predictors, including pooled cohort equations and the Seattle Heart Failure score. The results of the study were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

"We were excited to find that machine learning can leverage unstructured datasets such as medical images and videos to improve on a wide range of clinical prediction models," said Chris Haggerty, Ph.D., co-senior author and assistant ...

2021-02-08

A type of cell derived from human stem cells that has been widely used for brain research and drug development may have been leading researchers astray for years, according to a study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The cell, known as an induced Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (iBMEC), was first described by other researchers in 2012, and has been used to model the special lining of capillaries in the brain that is called the "blood-brain barrier." Many brain diseases, including brain cancers as well as degenerative ...

2021-02-08

Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA ...

2021-02-08

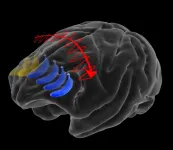

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

2021-02-08

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

2021-02-08

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

2021-02-08

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Mixed and matched: Integrating metal-organic frameworks into polymers for CO2 separation

New strategy boosts the performance of membranes for filtering CO2 from industrial emissions