(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - We know that what happens in the mouth doesn't stay in the mouth - but the oral cavity's connection to the rest of the body goes way beyond chewing, swallowing and digestion.

The healthy human oral microbiome consists of not just clean teeth and firm gums, but also energy-efficient bacteria living in an environment rich in blood vessels that enables the organisms' constant communication with immune-system cells and proteins.

A growing body of evidence has shown that this system that seems so separate from the rest of our bodies is actually highly influential on, and influenced by, our overall health, said Purnima Kumar, professor of periodontology at The Ohio State University, speaking at a science conference this week.

For example, type 2 diabetes has long been known to increase the risk for gum disease. Recent studies showing how diabetes affects the bacteria in the mouth help explain how periodontitis treatment that changes oral bacteria also reduces the severity of the diabetes itself.

Connections have also been found between oral microbes and rheumatoid arthritis, cognitive abilities, pregnancy outcomes and heart disease, supporting the notion that an unhealthy mouth can go hand-in-hand with an unhealthy body.

"What happens in your body impacts your mouth, and that in turn impacts your body. It's truly a cycle of life," Kumar said.

When the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) themed this year's annual meeting around dynamic ecosystems, Kumar saw an opportunity to put the mouth on the map, so to speak, as a vibrant microbial community that can tell us a lot about ourselves.

"What is more dynamic than the gateway to your body - the mouth? It's so ignored when you think about it, and it's the most forward-facing part of your body that interfaces with the environment, and it's connected to this entire tubing system," she said. "And yet we study everything but the mouth."

Kumar organized a session at the AAAS meeting today (Feb. 8, 2021) that she titled "Killer Smile: The Link Between the Oral Microbiome and Systemic Diseases."

The oral microbiome refers to the collection of bacteria - some helpful to humans and some not - that live inside our mouths.

Kumar has led and collaborated on recent research further explaining the link between oral health and type 2 diabetes, which was first described in the 1990s. She was the lead author of a 2020 study that compared the oral microbiomes of people with and without type 2 diabetes and how they responded to nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis.

The team found that periodontitis allows bacteria - rather than the human host - to take the reins in determining the mix of microbes and inflammatory molecules in the mouth. Treating the gum disease led to eventual restoration of a normal host-microbiome relationship, but it happened more slowly in people with diabetes.

"Our studies have led up to the conclusion that people with diabetes have a different microbiome from people who are not diabetic," Kumar said. "We know that changing the bacteria in your mouth and restoring them back to what your body knows as healthy and friendly bacteria actually improves your glycemic control."

Though there remains a lot to learn, the basics of these relationship between the oral microbiome and systemic disease have become clear.

Oral bacteria use oxygen to breathe and break down simple molecules of carbohydrates and proteins to stay alive. Something as simple as not brushing your teeth for a few days can set off a cascade of changes, choking off the oxygen supply and causing microbes to shift to a fermentative state.

"That creates a septic tank, which produces byproducts and toxins that stimulate the immune system," Kumar said. An acute inflammatory response follows, producing signaling proteins that bacteria see as food.

"Then this community - it's an ecosystem - shifts. Organisms that can break down protein start growing more, and organisms that can breathe in an oxygen-starved environment grow. The bacterial profile and, more importantly, the function of the immune system changes," she said.

The inflammation opens pores between cells that line the mouth and blood vessels get leaky, allowing what have become unhealthy bacteria to enter circulation throughout the body.

"The body is producing inflammation in response to these bacteria, and those inflammatory products are also moving to the bloodstream, so now you're getting hammered twice. Your body is trying to protect you and turning against itself," Kumar said. "And these pathogens are having a field day, crossing boundaries they were never supposed to cross."

The exact mechanisms of the links between the oral microbiome and specific diseases are complex and still being investigated, but the secret to a healthy mouth is no secret at all: Prevention of oral disease is as simple as brushing and flossing, and visiting the dentist twice a year for a professional cleaning, Kumar said.

The Office of the U.S. Surgeon General announced in 2018 that it had commissioned an update to its 2000 report on oral health, which was the first to be published on the topic.

Kumar said the national emphasis on oral health as an integral element of overall well-being bolsters her argument that the mouth should be an "equal opportunity player" in determinants of health.

"Putting the mouth back into the body - that's my goal here," she said.

INFORMATION:

Contact:

Purnima Kumar,

Kumar.83@osu.edu;

614-247-4532

Written by Emily Caldwell,

Caldwell.151@osu.edu

New research finds caffeine consumed during pregnancy can change important brain pathways that could lead to behavioral problems later in life. Researchers in the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) analyzed thousands of brain scans of nine and ten-year-olds, and revealed changes in the brain structure in children who were exposed to caffeine in utero.

"These are sort of small effects and it's not causing horrendous psychiatric conditions, but it is causing minimal but noticeable behavioral issues that should make us consider long term effects ...

One of humanity's biggest challenges right now is reducing our emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Research groups worldwide are trying to find ways to efficiently separate carbon dioxide (CO2) from the mixture of gases emitted from industrial plants and power stations. Among the many strategies for accomplishing this, membrane separation is an attractive, inexpensive option; it involves using polymer membranes that selectively filter CO2 from a mix of gases.

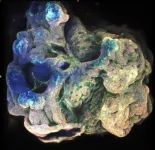

Recent studies have focused on adding low amounts of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) into polymer matrices to enhance their properties. MOFs are compounds made of a metallic center bonded to organic molecules in a very orderly fashion, producing porous crystals. When added to polymer ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- The world's most technologically advanced robots would lose in a competition with a tiny crustacean.

Just the size of a sunflower seed, the amphipod Dulichiella cf. appendiculata has been found by Duke researchers to snap its giant claw shut 10,000 times faster than the blink of a human eye.

The claw, which only occurs on one side in males, is impressive, reaching 30% of an adult's body mass. Its ultrafast closing makes an audible snap, creating water jets and sometimes producing small bubbles due to rapid changes in water pressure, a phenomenon known ...

Bark beetle outbreaks and wildfire alone are not a death sentence for Colorado's beloved forests--but when combined, their toll may become more permanent, shows new research from the University of Colorado Boulder.

It finds that when wildfire follows a severe spruce beetle outbreak in the Rocky Mountains, Engelmann spruce trees are unable to recover and grow back, while aspen tree roots survive underground. The study, published last month in Ecosphere, is one of the first to document the effects of bark beetle kill on high elevation forests' recovery from wildfire.

"The fact that Aspen is regenerating prolifically after wildfire is not a surprise," said Robert Andrus, who conducted ...

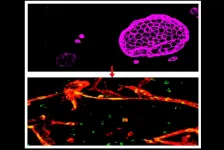

A team of engineers and scientists has developed a method of 'multiplying' organoids: miniature collections of cells that mimic the behaviour of various organs and are promising tools for the study of human biology and disease.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, used their method to culture and grow a 'mini-airway', the first time that a tube-shaped organoid has been developed without the need for any external support.

Using a mould made of a specialised polymer, the researchers were able to guide the size and shape of the mini-airway, grown from adult mouse stem cells, and then remove it from the mould when it reached ...

DANVILLE, Pa. - Researchers at Geisinger have found that a computer algorithm developed using echocardiogram videos of the heart can predict mortality within a year.

The algorithm--an example of what is known as machine learning, or artificial intelligence (AI)--outperformed other clinically used predictors, including pooled cohort equations and the Seattle Heart Failure score. The results of the study were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

"We were excited to find that machine learning can leverage unstructured datasets such as medical images and videos to improve on a wide range of clinical prediction models," said Chris Haggerty, Ph.D., co-senior author and assistant ...

A type of cell derived from human stem cells that has been widely used for brain research and drug development may have been leading researchers astray for years, according to a study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The cell, known as an induced Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (iBMEC), was first described by other researchers in 2012, and has been used to model the special lining of capillaries in the brain that is called the "blood-brain barrier." Many brain diseases, including brain cancers as well as degenerative ...

Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA ...

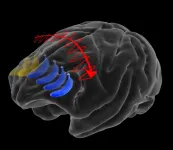

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...